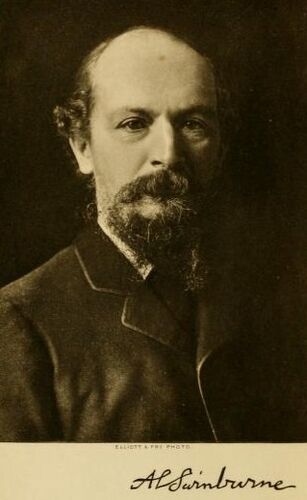

Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909), from The Poems of A.C. Swinburne, 1904. Courtesy Internet Archive.

| Algernon Charles Swinburne | |

|---|---|

| Born |

April 5 1837 London, England |

| Died |

April 10 1909 (aged 72) London, England |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright, novelist, and critic |

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 - 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and literary critic. He invented the roundel verse form, wrote several novels, and contributed to the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Life[]

Overview[]

Swinburne, son of Admiral Swinburne and of Lady Jane Ashburnham (daughter of the 3rd earl of Ashburnham), was born in London, received his early education in France, and was at Eton and at Oxford, where he attracted the attention of Jowett, and gave himself to the study of Latin, Greek, French, and Italian, with special reference to poetic form. He left Oxford without graduating in 1860, and in the next year published 2 plays, The Queen Mother and Rosamund, which made no impression on the public, though a few good judges recognised their promise. The same year he visited Italy, and there made the acquaintance of Walter Savage Landor On his return he lived for some time in Cheyne Row, Chelsea, with D.G. Rossetti, and G. Meredith. The appearance in 1865 of Atalanta in Calydon led to his immediate recognition as a poet of the highest order, and in the same year he published Chastelard: A tragedy, the 1st part of a trilogy relating to Mary Queen of Scots, the other 2 being Bothwell (1874), and Mary Stuart (1881). Poems and Ballads, published in 1866, created a profound sensation alike among the critics and the general body of readers by its daring departure from recognised standards, alike of politics and morality, and gave rise to a prolonged and bitter controversy, Swinsubne defending himself against his assailants in Notes on Poems and Reviews. His next works were the Song of Italy (1867) and Songs before Sunrise (1871). Returning to the Greek models which he had followed with such brilliant success in Atalanta he produced Erechtheus (1876), the extraordinary metrical power of which won general admiration.[1]

Algernon Charles Swinburne Life & Works

Swinburne belongs to the class of "Poets' poets." He never became widely popular. As a master of meter he is hardly excelled by any of our poets, but it has not seldom been questioned whether his marvelous sense of the beauty of words and their arrangement did not exceed the depth and mass of his thought. The Hymn to Artemis in Atalanta beginning "When the hounds of Spring are on Winter's traces" is certainly one of the most splendid examples of metrical power in the language. As a prose writer he occupies a much lower place, and here the contrast between the thought and its expression becomes very marked, the latter often becoming turgid and even violent. In his earlier days in London S. was closely associated with the pre-Raphaelites, the Rossettis, Meredith, and Burne-Jones: he was thus subjected successively to the classical and romantic influence, and showed the traces of both in his work. He was never m., and for the last 30 years of his life lived with his friend, Mr. Theodore Watts-Dunton, at the Pines, Putney Hill. For some time before his death he was almost totally deaf.[1]

Family and childhood[]

Drawing of Swinburne by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), 1860. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Swinburne was born in Chester Street, Grosvenor Place, London, the eldest child of Admiral Charles Henry Swinburne (1797-1877), by his wife Lady Jane Henrietta (1809-1896), daughter of George Ashburnham, 3rd earl of Ashburnham. His father was the 2nd son of Sir John Edward Swinburne (1762–1860), 6th baronet of Capheaton, in Northumberland. This baronet, who exercised a strong influence over his grandson, had been born and brought up in France, and cultivated the memory of Mirabeau. In habits, dress, and modes of thought he was like a French nobleman ,of the ancien regime. From his father, a cut and dried unimaginative old "salt," the poet inherited little but a certain identity of color and expression; his features and something of his mental character were his mothers. Lady Jane was a woman of exquisite accomplishment, and widely read in foreign literature.[2]

Algernon had been born all but dead and was not expected to live an hour; but though he was always nervous and slight, his childhood, spent mainly in the open air, was active and healthy. His parents were high-church and he was brought up as 'a quasi-catholic' He recollected in after years the enthusiasm with which he welcomed the process of confirmation, and his "ecstasies of adoration when receiving the Sacrament."[3]

From his earliest years he was trained, by his grandfather and by his mother, in the French and Italian languages. He was brought up, with the exception of long visits to Northumberland, in the Isle of Wight, his grandparents residing at The Orchard, Niton, Ventnor, and his parents at East Dene, Bonchurch.[2]

He early developed a love for climbing, riding, and swimming, and never cared, through life, for any other sports. His father, the admiral, taught him to plunge in the sea when he was still almost an infant, and he was always a fearless and, in relation to his physique, a powerful swimmer. "He could swim and walk for ever" (Lord Redesdale).[3]

He was prepared for Eton by Collingwood Forster Fenwick, rector of Brook, near Newport, Isle of Wight, who expressed his surprise at finding the child so deeply read in certain directions; Algernon having, from a very early age, been "privileged to have a book at meals" (Mrs. Disney Leith).[3]

Eton[]

He came to Eton at Easter 1849, arriving, "a queer little elf, who carried about with him a Bowdlerised Shakespeare, adorned with a blue silk book-marker, with a Tunbridge-ware button at the end of it" (Lord Redesdale). This volume had been given to him by his mother when he was 6 years of age.[3]

Up to the time of his going to Eton he had never been allowed to read a novel, but he immediately plunged into the study of Dickens, as well as of Shakespeare (released from Bowdler), of the old dramatists, of every species of lyrical poetry. The embargo being now raised, he soon began to read everything. It is difficult to say what, by the time he left Eton, "Swinburne did not know, and, what is more, appreciate, of English literature" (Sir George Young). He devoured even that dull gradus the Poetæ Græci, a book which he long afterwards said "had played a large part in fostering the love of poetry in his mind" (A.G.C. Liddell).[3]

In 1850 his mother gave him Dyce's Marlowe, and he soon knew Ford and Webster. He began, before he was 14, to collect rare editions of the dramatists. Any day he could be found in a bay-window of the college library, the sunlight in his hair, and his legs always crossed tailor-wise, with a folio as big as himself spread open upon his knees. The librarian, "Grub" Brown, used to point him out, thus, to strangers as one of the curiosities of Eton. He boarded at Joynes's, who was his tutor; Hawtrey was headmaster.[3]

It has been falsely said that Swinburne was bullied at Eton. On the contrary, there was "something a little formidable about him" (Sir George Young), considerable tact (Lord Redesdale), and a great, even audacious, courage, which kept other boys at a distance. He did not dislike Eton, but he cultivated few friendships; he did not desire school-honors, he never attempted any game or athletics, and he was looked upon as odd and inaccountable, and so left alone to his omnivorous reading. He was a kind of fairy, a privileged creature.[4]

Lord Redesdale recalls his taking "long walks in Windsor Forest, always with a single friend, Swinburne dancing as he went, and reciting from his inexhaustible memory the works which he had been studying in his favourite sunlighted window." Sir Greorge Young has described him vividly: "his hands and feet all going" while he talked; "his little white face, and great aureole of hair, and green eyes," the hair standing out in a bush of "three different colours and textures, orange-red, dark red, and bright pure gold." Charles Dickens, at Bonchurch in 1849, was struck with "the golden-haired lad of the Swinburnes" whom his own boys used to play with, and when he went to congratulate the poet on Atalanta in 1865, he reminded him of this earlier meeting.[4]

In 1851 Algernon "passed" in swimming, and at this time, in the holidays, caused some anxiety by his recklessness in riding and climbing; he swarmed up the Culver Cliff, hitherto held to be impregnable: a feat of which he was proud to the end of his life.[4]

Immediately on his arrival at Eton he had attacked the poetry of Wordsworth. In September 1849 he was taken by his parents to visit that poet in the Lakes; Wordsworth, who was very gracious, said in parting that he did not think that Algernon "would forget" him, whereupon the little boy burst into tears (Miss Sewell's Autobiography).[4]

Earlier in the same year Lady Jane had taken her son to visit Rogers in London; and on this old man also the child made a strong impression. Rogers laid his hand on Algernon's head in parting, and said "I think that you will be a poet, too!" He was, in fact, now writing verses, some of which his mother sent to Fraser's Magazine, where they appeared, with his initials, in 1849 and again in 1851; but of this "false start" he was afterwards not pleased to be reminded.[4]

It is interesting that at the age of 14 many of his lifelong partialities and prejudices were formed; in the course of 1851 we find him immersed in Landor, Shelley, and Keats, in the Orlando Furioso, and in the tragedies of Corneille, and valuing them as he did throughout his life; while, on the other hand, already hating Euripides, insensible to Horace, and injurious to Racine. In the catholicity of his poetic taste there was one odd exception: he had promised his mother, whom he adored, not to read Byron, and in fact did not open that poet till he went to Oxford.[4]

In 1852, reading much French with Tarver, Notre Dame de Paris introduced him to Victor Hugo. He now won the 2nd Prince Consort's prize for French and Italian, and in 1853 the 1st prizes for French and Italian. His Greek elegiacs were greatly admired. He was, however, making no real progress at school, and was chafing against the discipline; in the summer of 1853 he had trouble with Joynes, of a rebellious kind, and did not return to Eton, 'although nothing had been said during the half about his leaving' (Sir G. Young). When he left he was within a few places of the headmaster's division.[4]

In 1854 there was some talk of his being trained for the army, which he greatly desired; but this was abandoned on account of the slightness and shortness of his figure. All his life he continued to regret the military profession. He was prepared for Oxford, in a desultory way, by John Wilkinson, perpetual curate of Cambo in Northumberland, who said that he "was too clever and would never study." He now spent a few weeks in Germany with his uncle. General the Hon. Thomas Ashburnham.[4]

Oxford[]

On 24 Jan. 1856 Swinburne matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford, and he kept terms regularly through the years 1856. 1857, and 1858. After the first year his high-church proclivities fell from him and he became a nihilist in religion and a republican. He had portraits of Mazzini in his rooms, and declaimed verses to them (Lord Sheffield); in the spring of 1857 he wrote an "Ode to Mazzini," his earliest work of any maturity.[4]

In this year, while at Capheatop, he formed the friendship of Lady Trevelyan and Miss Capel Lofft, and was for the next 4 years a member of their cultivated circle at Wallington. Here Ruskin met him, and formed a very high opinion of his imaginative capacities. In the autumn Edwin Hatch introduced him to B.G. Rossetti, who was painting in the Union, and in December the earliest of Swinburne's contributions to Undergraduate Papers appeared. To this time belong his friendships with John Nichol, [Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, and Spencer Stanhope.[4]

Early in 1858 he was writing his tragedy of Rosamond and a poem on "Tristram," and planning a drama on The Albigenses. In March 1858 Swinburne dined at Farringford with Tennyson, who thought him 'a very modest and intelligent young fellow' and read Maud to him, urging upon him a special devotion to Virgil. In April the last of the Undergraduate Papers appeared. In the Easter term Swinburne took a second in moderations, and won the Taylorian' scholarship for French and Italian.[4]

He now accompanied his parents to France for a long visit. The attempt of Orsini, in January 1858, to murder Napoleon III had found an enthusiastic admirer in Algernon, who decorated his rooms at Oxford with Orsini's portrait, and proved an embarrassing fellow-traveller in Paris to his parents. He kept the Lent and Easter terms of 1859 at Balliol, and when the Austrian war broke out in May, he spoke at the Union, "reading excitedly but ineffectively a long tirade against Napoleon and in favour of Orsini and Mazzini" (Lord Sheffield).[4]

He began to be looked upon as "dangerous," and Jowett, who was much interested in him, expressed an extreme dread that the college might send him down and so "make Balliol as ridiculous as University had made itself about Shelley." At this time Swinburne had become what he continued to be for the rest of his life, a high tory republican. He cultivated few friends except those who immediately interested him poetically and politically. But he was a member of the club called the Old Mortality, in which he was associated with Nichol, Dicey, Luke (who was drowned in 1861), T.H. Green, Caird, and Pater, besides Mr. Bryce and Mr. Bywater.[4]

Jowett thought it well that Swinburne should leave Oxford for a while at the end of Easter term, 1859, and sent him to read modern history with William Stubbs at Navestock. Here Swinburne recited to his host and hostess a tragedy he had just completed (probably The Queen Mother). In consequence of some strictures made by Stubbs, Swinburne destroyed the only draft of the play, but was able to write it all out again from memory.[4]

He was back at the university from 14 October to 21 November, when he was principally occupied in writing a 3-act comedy in verse in the manner of Fletcher, now lost; it was called Laugh and Lie Down. He had lodgings in Broad Street, where the landlady made complaints of his late hours and general irregularities.[4]

1860s[]

Portrait by William Bell Scott (1811-1890), circa 1860. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Jowett was convinced that Swinburne was doing no good at Oxford, and he left without taking a degree. His father was greatly displeased with him, but Algernon withdrew to Capheaton, until, in the spring of 1860, he came to London, and took rooms near Russell Place to be close to the Burne-Joneses. He had now a very small allowance from his father, and gave up the idea of preparing for any profession. Capheaton was still his summer home, but when Sir John Swinburne died (26 Sept. 1860) Algernon stayed with William Bell Scott' in Newcastle for some time. His first book, The Queen Mother and Rosamond, was published before Christmas; it fell dead from the press.[4]

When Algernon returned to London early in 1861,[4] his friendship with D.G. Rossetti became close; for the next 10 years they "lived on terms of affectionate intimacy; shaped and coloured, on his side, by cordial kindness and exuberant generosity, on mine by gratitude as loyal and admiration as fervent as ever strove and ever failed to express all the sweet and sudden passion of youth towards greatness in its elder" (from an unpublished statement, written by Swinburne in 1882). This was by far the most notable experience in Swinburne's career. Rossetti developed, restrained, and guided, with marvellous skill, the genius of "my little Northumbrian friend," as he used to call him.[5]

Under Rossetti's persuasion Swinburne was now writing some of his finest early lyrics, and was starting a cycle of prose tales, to be called The Triameron; this was to consist of some 20 stories. Of these, "Dead Love" alone was printed in his lifetime; but several others exist unpublished, the most interesting being "The Marriage of Mona Lisa," "A Portrait," and "Queen Fredegonde."[5]

In the summer of 1861 he was introduced to Monckton Milnes, who actively interested himself in Swinbume's career. Early in 1862 Henry Adams, the American writer, then acting as Monckton Milnes's secretary, met Swinburne at Fryston on an occasion which he has described in his privately printed diary. The company also included Stirling of Keir (afterwards Sir W. Stirling-Maxwell) and Laurence Oliphant, and all Milnes's guests made Swinburne's acquaintance for the first time. He reminded Adams of "a tropical bird," "a crimson macaw among owls"; and it was on this occasion that Stirling, in a phrase often misquoted, likened him to "the Devil entered into the Duke of Argyll." All the party, though prepared by Milnes's report, were astounded at the flow, the volume and the character of the young man's conversation; "Voltaire's seemed to approach nearest to the pattern;" "in a long experience, before or after, no one ever approached it." The men present were brilliant and accomplished, but they "could not believe in Swinburne's incredible memory and knowledge of literature, classic, mediæval and modern, nor know what to make of his rhetorical recitation of his own unpublished lyrics."[5]

These parties at Fryston were probably the beginning of the social legend of Swinburne, which preceded and encouraged the reception of his works a few years later. It was at Milnes's house that he met and formed an instant friendship with Richard Burton. The relationship which ensued was not altogether fortunate. Burton was a giant and an athlete, one of the few men who could fire an old-fashioned elephant-gun from his shoulder, and drink a bottle of brandy without feeling any effect from it. Swinburne, on the contrary, was a weakling. He tried to compete with the "hero" in Dr. Johnson's sense, and he failed.[5]

The physical characteristics of Algernon Swinburne were so remarkable as to make him almost unique. His large head was out of all proportion with his narrow and sloping shoulders; his slight body, and small, slim extremities, were agitated by a restlessness that was often, but not correctly, taken for an indication of disease. Alternately he danced as if on wires or sat in an absolute immobility.[6]

The quick vibrating motion of his hands began in very early youth, and was a sign of excitement; it was accompanied, even when he was a child, by "a radiant expression of his face, very striking indeed" (Isabel Swinburne).[6] His puny frame required little sleep, seemed impervious to fatigue, was heedless of the ordinary incentives of physical life; he inherited a marvellous constitution, which he impaired in early years, but which served his old age well.[7]

His character was no less strange than his physique. He was profoundly original, and yet he took the colour of his surroundings like a chameleon. He was violent, arrogant, even vindictive, and yet no one could be more affectionate, more courteous, more loyal. He was fierce in the defence of his prejudices, and yet dowered with an exquisite modesty. He loved everything that was pure and of good report, and yet the extravagance of his language was often beyond the reach of apology. His passionate love for very little children was entirely genuine and instinctive, and yet the forms of it seemed modelled on the expressions of Victor Hugo.[7]

He was being painted by Rossetti in February 1862 when the wife of the latter died so tragically; Swinburne gave evidence at the inquest (12 Feb.). In the spring of that year he joined his family in the Pyrenees, and saw the Lac de Gaube, in which he insisted on swimming, to the horror of the natives. He was now friends with George Meredith, who printed, shortly before his death, an account of the overwhelming effect of FitzGerald's Rubaiyat upon Swinburne, and the consequent composition of Laus Veneris, probably in the spring of 1862.[5]

Early writing[]

In this year Swinburne began to write, in prose as well as in verse, for the Spectator, which printed "Faustine" and 6 other important poems, and (6 Sept.) a very long essay on Baudelaire's Fleurs du Mal, written "in a Turkish bath in Paris." A review of one of Victor Hugo's books, forwarded to the French poet, opened his personal relations with that chief of Swinburne's literary heroes. He now finished Chastelard, on which he had long been engaged, and in October his prose story, "Dead Love," was printed in Once a Week (this appeared in book form in 1864).[5]

Swinburne joined Meredith and the Rossettis (24 Oct. 1862) in the occupation of Tudor House, 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. Rossetti believed that it would be good for Swinburne to be living in the household of friends who would look after him without seeming to control him, since life in London lodgings was proving rather disastrous. Swinburne's extremely nervous organisation laid him open to great dangers, and he was peculiarly unfitted for dissipation. Moreover, about this time he began to be afficted with what is considered to have been a form of epilepsy, which made it highly undesirable that he should be alone.[5]

In Paris, during a visit in March 1863, he had made the acquaintance of Whistler, whom he now introduced to Rossetti. Swinburne became friendly with Whistler's family, and after a fit in the summer of 1863 in the American painter's studio, he was nursed through the subsequent illness by Whistler's mother. On his convalescence he was persuaded, in October, to go down to his father's house at East Dene, near Bonchurch, where he remained for 5 months and entirely recovered his health and spirits. He brought with him the opening of Atalanta in Calydon, which he completed at East Dene. For a story called ' The Children of the Chapel,' which was being written by his cousin, Mrs. Disney Leith, he wrote at the same time a morality, "The Pilgrimage of Pleasure," which appeared, without his name, in March 1864.[8]

From the Isle of Wight, at the close of February 1864, Swinburne went abroad for what was to remain the longest foreign tour in his life. He passed through Paris, where he saw Fantin-Latour, and proceeded to Hyeres, where Milnes had a villa, and so to Italy. From Rossetti he had received an introduction to Sejmaour Kirkup, then the centre of a literary circle in Florence, and Milnes added letters to Landor and to Mrs. Gaskell. Swinburne found Landor in his house in Via della Chiesa, close to the church of the Carmine, on 31 March, and he visited the art-galleries of Florence in the company of Mrs. Gaskell. In a garden at Fiesole he wrote "Itylus" and "Dolores." Before returning he made a tour through other parts of Italy.[8]

2 autumn months of 1864 were spent in Cornwall, at Tintagel (in company with Jowett), at Kynance Cove, and at St. Michael's Mount. On Swinburne's return to London he went into lodgings at 22a Dorset Street, where he remained for several years.[8]

Public notoriety[]

Atalanta in Calydon, in a cream-colored binding with mystical ornaments by D.G. Rossetti, was published by Edward Moxon in April 1865. At this time Smnburne, although now entering his 29th year, was entirely unknown outside a small and dazzled circle of friends, but the success of Atalanta was instant and overwhelming. Ruskin welcomed it as "the grandest thing ever done by a youth — though he is a Demoniac youth" (E.T. Cook's Life of Ruskin).[8]

In consequence of its popularity, the earlier tragedy of Chastelard was now brought forward and published in December of the same year. This also was warmly received by the critics, but there were murmurs heard as to its supposed sensuality. This was the beginning of the outcry against Swinburne's literary morals, and even Atalanta was now searched for evidences of atheism and indelicacy.[8]

He met, on the other hand, with many assurances of eager support, and in particular, in November 1865, he received a letter from a young Welsh squire, George E.J. Powell of Nant-Eos (1842-82), who soon became, and for several years remained, the cloeest of Swinburne's friends. The collection of lyrical poems, written during the last 8 years, which was now almost ready, was felt by Swinburne's circle to be still more dangerous than anything which he had yet published; early in 1866 (probably in January) the long ode called Laus Veneris was printed in pamphlet form, as the author afterwards stated, "more as an experiment to ascertain the public taste — and forbearance! — than anything else. Moxon, I well remember, was terribly nervous in those days, and it was only the wishes of mutual good friends, coupled with his own liking for the ballads, that finally induced him to publish the book at all."[8]

The text of this herald edition of Laus Veneris differs in many points from that included in the volume of Poems and Ballads which eventually appeared at the end of April 1866. The critics in the press denounced many of the pieces with a heat which did little credit to their judgment. Moxon shrank before the storm, and in July withdrew the volume from circulation. Another publisher was found in John Camden Hotten, to whom Swinburne now transferred all his other books.[8]

There had been no such literary scandal since the days of Don Juan, but an attempt at prosecution fell through, and Ruskin, who had been requested to expostulate with the young poet, indignantly replied "He is infinitely above me in all knowledge and power, and I should no more think of advising or criticising him than of venturing to do it to Turner if he were alive again."[8]

Swinburne now found himself the most talked-of man in England, but all this violent notoriety was unfortunate for him, morally and physically. He had a success of curiosity at the annual dinner of the Royal Literary Fund (2 May 1866), where, Lord Houghton being in the chair, Swinburne delivered the only public speech of his life; it was a short critical essay on "The Imaginative Literature of England" committed to memory. In the autumn he spent some time with Powell at Aberystwyth.[9]

His name was constantly before the public in the latter part of 1866, when his portraits filled the London shop-windows and the newspapers outdid one another in legendary tales of his eccentricity. He had published in the summer a selection from Byron, with an introduction of extreme eulogy, and in October he answered his critics in "Notes on Poems and Reviews". William Michael Rossetti also published a volume in defence.[9]

The winter was spent at Holmwood, near Henley-on-Thames, which his father bought in 1865, and where his family was now settled; here in November he finished a large book on Blake, which had occupied him for some time, and in February 1867 completed A Song of Italy, which was published in September. His friends now included Simeon Solomon, whose genius he extolled in the Dark Blue magazine (July 1871) and elsewhere. In April 1867, on a false report of the death of Charles Baudelaire (who survived until September of that year), Swinburne wrote "Ave atque Vale."[9]

This was a period of wild extravagance and of the least agreeable episodes of his life; his excesses told upon his health, which had already suffered, and there were several recurrences of his malady. In June, while staying with Lord Houghton at Fryston, he had a fit which left him seriously ill. In August, to recuperate, he spent some time with Lord Lytton at Knebworth, where he made the acquaintance of John Forster.[9]

In November he published the pamphlet of political verse called An Appeal to England. The Reform League invited him to stand for parliament ; Swinburne appealed to Mazzini, to whom he had been introduced, in March 1867, by Karl Blind. Mazzini strongly discouraged the idea, advising him to confine himself to the cause of Italian freedom, and he declined.[9]

Swinburne now became friendly with Adah Isaacs Menken, who had left her 4th and last husband, James Barclay. It has often been repeated that the poems of this actress, published as Infelicia early in 1868, were partly written by Swinburne, but this is not the case ; and the verses, printed in 1883, as addressed by him to Adah Menken, were not composed by him. She went to Paris in the summer of 1868 and died there on 10 August; the shock to Swinburne of the news caused an illness which lasted several days, for he was sincerely attached to her.[9]

He was very busily engaged on political poetry during this year. In February 1868 he wrote "The Hymn of Man," and in April "Tiresias"; in June he published, in pamphlet form, Siena. 2 prose works belong to this year: William Blake and "Notes on the Royal Academy," but most of his energy was concentrated on the transcendental celebration of the Republic in verse.[9]

At the height of the scandal about Poems and Ballads there had been a meeting between Jowett and Mazzini at the house of George Howard (afterwards 9th earl of Carlisle), to discuss "what can be done with and for Algernon." Mazzini had instructed Karl Blind to bring the poet to visit him, and had said "There must be no more of this love-frenzy; you must dedicate your glorious powers to the service of the Republic." Swinburne's reply had been to sit at Mazzini's feet and to pour forth from memory the whole of "A Song of Italy." For the next 3 years he carried out Mazzini's mission, in the composition of Songs before Sunrise.[9]

His health was still unsatisfactory; he had a fit in the reading-room of the British Museum (10 July), and was ill for a month after it. He was taken down to Holmwood, and when sufficiently recovered started (September) for Étretat, where he and Powell hired a small villa which they named the Chaumière de Dolmancé. Here Offenbach visited them. The sea-bathing was beneficial, but on his return to London Swinburne's illnesses, fostered by his own obstinate imprudence, visibly increased in severity; in April 1869 he complained of "ill-health hardly intermittent through weeks and months." From the end of July to September he spent some weeks at Vichy with Richard Burton, Leighton, and Mrs. Sartoris. He went to Holmwood for the winter and composed 'Diræ' in December.[9]

In the summer of 1870 he and Powell settled again at Étretat; during this visit Swinburne, who was bathing alone, was carried out to sea on the tide and nearly drowned, but was picked up by a smack, which carried him in to port. At this time, too, the youthful Guy de Maupassant paid the friends a visit, of which he has given an entertaining account. When the Germans invaded France, Swinburne and Powell returned to England. In September Swinburne published the "Ode on the Proclamation of the French Republic". He now reappeared, more or less, in London artistic society, and was much seen at the houses of John Westland Marston and Ford Madox Brown.[9]

1870s[]

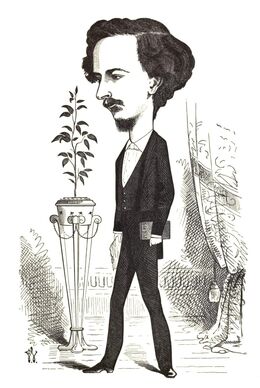

"A.C. Swinburne, a true poet." Caricatureby Frederick Waddy (1848-1901) from Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day, 1873. Courtesy Wikisource.

Songs before Sun-rise, with its prolonged glorification of the republican ideal, appeared early in 1871. In July and August of this year Swinburne stayed with Jowett in the little hotel at the foot of Loch Tummel.[9] Here he made the acquaintance of Browning, who was writing Hohenstiel-Schwangau. Browning was staying near by, and often joined the party. Swinburne, much recovered in health, was in delightful spirits; like Jowett, he was ardently on the side of France.[10]

In September he went off for a prolonged walking-tour through the highlands of Scotland, and returned in splendid condition. The life of London, however, was always bad for him, and in October he was seriously ill again; in November he visited George Meredith at Kingston.[10]

He was now mixed up in much violent polemic with Robert Buchanan and others; early in 1872 he published the most effective of all his satirical writings, the pungent "Under the Microscope". He had written the opening act of Bothwell,' which Locker-Lampson set up in type for him; this play, however, was not finished for several years.[10]

His relations with D.G. Rossetti had now ceased; his acquaintance with Mr. Theodore Watts (afterwards Watts-Dunton) began. In July and August of this year he was again staying at Tummel Bridge with Jowett, and once more he was the life and soul of the party, enlivening the evenings with paradoxes and hyperboles and recitations of Mrs. Gamp. Jowett here persuaded Swinburne to join him in revising the Children's Bible of J.D. Rogers, which was published the following summer.[10]

In May 1873 the violence of Swinburne's attacks on Napoleon III (who was now dead) led to a remarkable controversy in the Examiner and the Spectator. Swinburne had given up his rooms in Dorset Street, and lodged for a short time at 12 North Crescent, Alfred Place, from which he moved, in September 1873, to rooms at 3 Great James Street, where he lived until he left London for good. Meanwhile he spent some autumn weeks with Jowett at Grantown, Elginshire. During this year he was busily engaged in writing Bothwell, to which he put the finishing touches in February 1874, and published some months later.[10]

The greater part of January 1874 he spent with Jowett at the Land's End. Between March and September he was in the country, first at Holmwood, afterwards at Niton in the Isle of Wight. In April 1874 he was put, without his consent, and to his great indignation, on the Byron Memorial Committee. He was at this time chiefly devoting himself to the Elizabethan dramatists; an edition, with critical introduction, of Cyril Tourneur had been projected at the end of 1872, but had been abandoned; but the volume on George Chapman was issued, in 2 forms, in December 1874.[10]

This winter was spent at Holmwood, where in February 1875 Swinburne issued his introduction to the reprint of Wells's Joseph and his Brethren. From early in June until late in October he was out of London — at Holmwood; visiting Jowett at West Malvern, where he sketched the first outline of "Erechtheus"; and in apartments at Middle Cliff, Wangford, near Southwold, in Suffolk.[10]

His monograph on 'Auguste Vacquerie,' in French, was published in Paris in November 1875; the English version appeared in the 'Miscellanies' of 1886. 2 volumes of reprinted matter belong to this year, 1876: in prose Essays and Studies, in verse Songs of Two Nations; and a pseudonymous pamphlet, attacking Buchanan, entitled The Devil's Due.[10]

Most of 1876 was spent at Holmwood, with brief and often untoward visits to London. In July he was poisoned by lilies with which a too enthusiastic hostess had filled his bedroom, and he did not completely recover until November. In the winter of this year appeared Erechtheus and "A Note on the Muscovite Crusade," and in December was written "The Ballad of Bulgarie," first printed as a pamphlet in 1893. Admiral Swinburne, his father, died on 4 March 1877. The poet sent his Charlotte Bronte to press in June, and then left town for the rest of the year, which he spent at Holmwood and again at Wangford, where he occupied himself in translating the poems of François Villon. He also issued, in a weekly periodical, his unique novel entitled A Year's Letters, which he did not republish until 1905, when it appeared as Love's Cross-currents.[10]

In April 1878 Victor Hugo talked of addressing a poem of invitation to Swinburne, and a committee invited the latter to Paris in May to be present as the representative of English poetry at the centenary of the death of Voltaire; but the condition of his health, which was deplorable during this year and the next, forbade his acceptance. In 1878 his chief publication was Poems and Ballads: Second series.[10]

Swinburne's state became so alarming that in September 1879 Theodore Watts, with the consent of Lady Jane Swinburne, removed him from 3 Great James Street to his own house, The Pines, Putney, where the remaining 30 years of his life were spent, in great retirement but with health slowly and completely restored. [10] Under the guardianship of his devoted companion, he pursued with extreme regularity a monotonous course of life, which was rarely diversified by even a visit to London, although it lay so near.[6]

Swinburne had, since about 1875, been afflicted with increasing deafness, which now (from 1879 onwards) made general society impossible for him. In 1880 he published 3 important volumes of poetry, Studies in Song, Heptalogia (an anonymous collection of 7 parodies), and Songs of the Springtides; and a volume of prose criticism, A Study of Shakespeare.[6]

1880s[]

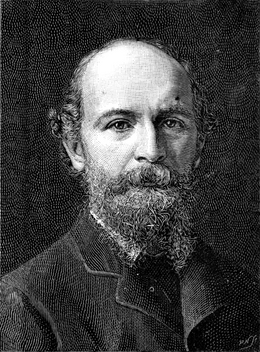

Swinburne aged 52 (1889-90), from The Strand 1:1 (January 1891). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In April 1881 he finished the long ode entitled "Athens," and began Tristram of Lyonesse; Mary Stuart was published in this year. In February 1882 he made the acquaintance of James Russell Lowell, who had bitterly attacked his early poems. Lowell was now "very pleasant" and the old feud was healed. In April, as he was writing the last canto of Tristram,' he was surprised by the news of D.G. Rossetti's death, and he wrote his "Record of Friendship." In August Watts took him for some weeks to Guernsey and Sark. In September, as he "wanted something big to do," Swinburne started a Life and Death of Caesar Borgia, of which the only fragment that remains was published in 1908 as "The Duke of Gandia."[6]

The friends proceeded to Paris for the dinner to Victor Hugo (22 Nov.) and the resuscitation of Le Roi s'amuse at the Theatre Fran9ais. Swinburne was introduced for the first time to Hugo and to Leconte de Lisle, but he could not hear the play, and on his return to Putney he refused to go to Cambridge to listen to the Ajax, his infirmity now excluding him finally from public appearances.[6]

To 1883 belongs A Century of Roundels, which made Tennyson say "Swinburne is a reed through which all things blow into music." In June of that year Swinburne visited Jowett at Emerald Bank, Newlands, Keswick.[6]

His history now dwindles to a mere enumeration of his publications. A Midsummer Holiday appeared im 1884, Marino Fahero in 1885, A Study of Victor Hugo and Miscellanies in 1886, Locrine and a group of pamphlets of verse (A Word for the Navy, The Question, The Jubilee, and Gathered Songs) in 1887.[6]

In June 1888 his public rupture with an old friend. Whistler, attracted notice; it was the latest ebullition of his fierce temper, which was now becoming wonderfully placid. His daily walk over Putney Heath, in the course of which he would waylay perambulators for the purpose of baby-worship, made him a figure familiar to the suburban public.[6]

Swinburne's summer holidays, usually spent at the sea-side with his inseparable friend, were the sources of much lyrical verse. In 1888 he wrote 2 of the most remarkable of his later poems: "The Armada" and "Pan and Thalassius." In 1889 he published A Study of Ben Jonson and Poems and Ballads: Third series.[6]

Last years[]

Swinburne's marvelous fecundity was now at length beginning to slacken; for some years he made but slight appearances. Hia last publications were: The Sisters (1892); Studies in Prose and Poetry (1894); Astrophel (1894); The Tale of Balen (1896); Rosamund, Queen of the Lombards (1899); A Channel Passage (1904); and Love's Cross-Currents — a reprint of the novel A Year's Letters of 1877 — in 1905. In that year he wrote a little book about Shakespeare, which was published posthumously in 1909.[6]

In November 1896 Lady Jane Swinburne died, in her 88th year, and was mourned by her son in the beautiful double elegy called "The High Oaks: Barking Hall."[6]

Swinburne's last years were spent in great placidity, always under the care of his faithful companion. In November 1903 he caught a chill, which developed into double pneumonia, of which he very nearly died. Although, under great care, he wholly recovered, his lungs remained delicate.[6]

In April 1909, just before the poet's 72nd birthday, the entire household of Watts-Dunton was prostrated by influenza. In the case of Swinburne, who suffered most severely, it developed into pneumonia, and in spite of the resistance of his constitution the poet died on the morning of 10 April 1909.[6]

He was buried on 15 April at Bonchurch, among the graves of his family. He left only one near relation behind him, his youngest sister, Miss Isabel Swinburne.[6]

Ancestry[]

| Ancestors of Algernon Charles Swinburne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Writing[]

Swinburne is considered a decadent poet, although he perhaps professed to more vice than he actually indulged in; Oscar Wilde stated that Swinburne was "a braggart in matters of vice, who had done everything he could to convince his fellow citizens of his homosexuality and bestiality without being in the slightest degree a homosexual or a bestializer."[11]

It is a very remarkable circumstance, which must be omitted in no outline of his intellectual life, that his opinions, on politics, on literature, on art, on life itself, were formed in boyhood, and that though he expanded he scarcely advanced in any single direction after he was 20. If growth had continued as it began, he must have been the prodigy of the world, but his development was arrested, and he elaborated for 50 years the ideas, the convictions, the enthusiasms which he possessed when he left college.[7]

Even his art was at its height when he was 25, and it was the volume and not the vigour that increased. As a magician of verbal melody he impressed his early contemporaries to the neglect of his merit as a thinker, but posterity will regard him as a philosopher who gave melodious utterance to ideas of high originality and value. This side of his genius, exemplified by such poems as "Hertha" and "Tiresias", was that which showed most evidence of development, yet his masterpieces in this kind also were mainly written before he was 35.[7]

No complete collection of Swinburne's works has appeared, but his poems were published in 6 volumes in 1904, and his tragedies in 5 in 1905-1906.[7]

Swinburne devised the poetic form Roundel, a variation of the French Rondeau form, and some were included in A Century of Roundels dedicated to Christina Rossetti. Swinburne wrote to Edward Burne-Jones in 1883: "I have got a tiny new book of songs or songlets, in one form and all manner of metres ... just coming out, of which Miss Rossetti has accepted the dedication. I hope you and Georgie [his wife Georgiana, one of the MacDonald sisters] will find something to like among a hundred poems of nine lines each, twenty-four of which are about babies or small children". Opinions of these poems vary between those who find them captivating and brilliant, to those who find them merely clever and contrived. One of them, A Baby's Death, was set to music by English composer Sir Edward Elgar as the song Roundel: The little eyes that never knew Light.

T.S. Eliot read Swinburne's essays on the Shakespearean and Jonsonian dramatists in The Contemporaries of Shakespeare and The Age of Shakespeare and Swinburne's books on Shakespeare and Jonson. In The Sacred Wood: Essays on poetry and criticism, Eliot wrote that as a poet writing notes on poets, Swinburne had mastered his material, writing "he is more reliable to them than Hazlitt, Coleridge, or Lamb: and his perception of relative values is almost always correct." However, Eliot disliked Swinburne's prose. About this he wrote "the tumultuous outcry of adjectives, the headstrong rush of undisciplined sentences, are the index to the impatience and perhaps laziness of a disorderly mind."

Critical introduction[]

by Edmund Gosse

The gift by which Swinburne first won his way to the hearts of a multitude of readers was unquestionably the melody of his verse. The choruses in Alalanta in Calydon and the metrical inventions in Poems and Ballads acted on the ear of his contemporaries like an enchantment. Swinburne carried the prosody of the romantic age to its extreme point of mellifluousness, and he introduced into it a quality of speed, of throbbing velocity, which no one, not even Shelley, had anticipated.

In some of the odes in Songs before Sunrise he went even farther, and produced effects of such sonorous volume and such elaborate antiphonal harmony that it was obvious that English verse, along those lines, could proceed no farther. In point of fact, after 1871, it did proceed no farther even in Swinburne’s own hands, his later efforts to surpass his own miraculous virtuosity being less and less completely satisfactory, and indeed more and more like an imitation of himself. The poem called "Mater Triumphalis" may be taken as the extreme instance of Swinburne’s redundant volubility of sound before his talent in this direction began to decline, and we may hold it to be certain that in this species of prosody, about which a strong heretical reaction has long ago begun to set in, no other poet will ever surpass or even equal Swinburne.

This undisputed mastery in regular verse has, however, from the first tended to obscure the intellectual and imaginative qualities of a poet who was almost more directly and exclusively endowed with them than anyone else who ever lived. There may, that is to say, have been greater poets than he, but none was ever more penetrated with a sense of his high calling, or enjoyed an intenser exhilaration in the performance of it. He was preserved by a remarkable strain of common sense from losing his sanity and even from plunging into extravagance, but he was always at the edge of frenzy, always simmering on the flames of his enthusiasm.

This high literary temperature of Swinburne’s was one of his most notable characteristics, and it must be borne in mind in every attempt to estimate the value of his work. It gave to his poems an impression of heat and speed, a sort of volcanic impetus, which delighted those who liked it and infuriated those who did not. In the beginning, it was impossible to estimate the poems of Swinburne without prejudice. There is still no recent figure more difficult to approach judicially.

To begin to comprehend him we must perceive that he was completely dominated by the intuitive forms of sensibility, in the Kantian sense. His mind and character are neither intelligible nor worthy of attention unless we regard them from the æsthetic point of view. Other great poets present various facets of being which may not be so important or so striking as their literary side, but are perceptible. Swinburne alone is a man of letters, or nothing at all.

His long life offers us a series of extraordinary negatives; he was never married, he was never responsible for the career of another human being, he possessed no home of his own, he exercised no business or profession, he passed through the years like the fabulous Bird of Paradise, which never perched, because it had no feet. Swinburne never perched, but we may pursue the image so far as to say that when he was weary of his ceaseless flight, in middle age, he sank upon a nest from which he never had the energy to rise again. Charles Darwin tells us that “birds appear to be the most æsthetic of all animals”; Swinburne, who was often compared with a bird, was the most æsthetic of all human beings.

The dullness of his final 30 years in a sort of voluntary captivity at Putney has tended to obscure the picturesque legend of his prime, to which it is essential that memory should return. His childhood and early youth — contrary to the customary idea — were not artistically productive; his old age was monotonous and insipid; but there was a middle period of about 20 years in which he flamed like a comet right across our poetical heavens. This period extended from his last term at Oxford to the rapid decline of his energy when he had passed his 40th birthday. During the earlier half of this part of his career he was known only to a close circle of admirers; from 1865 to 1875, or a little later, he was the cynosure and centre of public curiosity, awakening in the latter case such passions of adoration and loathing, rapture and fear, as literature had wholly ceased to rouse since 1815.

He represented to a dazzled generation the uncontrolled worship of beauty, and he did so with unrivalled power because he was so disinterested. The world was astonished at the phenomenon of a voice which rang out like that of the angel of the Morning Star, and which yet, so far as action went, was nothing but a voice. Swinburne reminded us of the hero of Gautier’s novel (which he admired so extravagantly) "dont la sensualité imaginative s’est compliquée et raffinée, avant l’expérience, dans les musées et les bibliothèques" ["whose imaginative sensuality was complicated and refined, before experience, in museums and libraries"]. Swinburne displayed a prodigious sensibility, which was fed on books and pictures, not on life.

We shall, therefore, not merely fail to appreciate the position of Swinburne, but stumble blindly in our examination of his qualities, if we do not begin by perceiving that, to a degree unparalleled, he was cerebral in all his forces. He was an unbodied intelligence “hidden in the light of thought,” showering a rain of melody from some altitude untouched by the drawbacks and privileges of mortality. Tennyson might have been a farmer, Browning a stock-broker; Rossetti was a painter and Morris an upholsterer; but it is impossible to conceive Swinburne as “taking up” any species of useful employment.

To our great good fortune, he was possessed of what are called “moderate means,” which happily clung to him, by no conscious effort of his own, to the end of his days. He was therefore able to spin out his dream and his music without any species of material disturbance, his only approaches to “action” being the chimerical controversies, always on æsthetic questions, in which he engaged with mimic fury. These were to him what golf is to other ageing men: they were a form of health-preserving exercise.

It might have been supposed that a being so isolated from the common occupations of mankind, and so exclusively saturated in literature, would be imitative, artificial, and ineffective when he came to the task of composition. But the paradox is that Swinburne, soaked as he was in the wisdom of the ages, responsive like an Æolian harp to every breath of the wind of past poetry, is one of the most definitely original of all writers. He is himself to a fault, to our positive impatience and annoyance; he has a quality of style, a sort of perfume, which is so exclusively his own that it vexes us when or where it ceases to please us. Swinburne was a master of every artifice of imitation, and yet — except where he is intentionally a parodist — he is instantly recognizable under all disguises. He floods whatever he touches with his own pungent musk.

By heritage on both sides Algernon Swinburne was an aristocrat, and of his descent and bringing-up he retained something perceptible in his poetry — its fastidiousness, its independence — which was affected neither by popular prejudice nor by the authority of tradition. In private life his manners were affable and gracious, but they were ceremonious too; and we may see in his poetical attitude a distinct trace of hauteur. Apart from this emphasis, this touch of conscious dignity, there was in his original gesture towards literature a certain arrogant disregard of public taste, a disdain which was of the aristocratic order.

At a marvellously early age, and apparently by unaided instinct, he discovered the poets who were, to the very close of his life, to remain his most cherished companions. The little Eton schoolboy who selected Landor, Marlowe, and Catullus as his favourite writers, without the smallest affectation, because they pleased him best, because they thrilled him with rapture, might be expected, when, long years later, he too became a writer, to trouble himself not a whit about the accepted fashions of the hour.

Swinburne’s attitude of rebellion was not plainly discerned, though it was indicated, in his earlier publications, which were all of the dramatic order. But from 1859 until he published Poems and Ballads in 1866 he was preparing what amounted to a lyrical and therefore apparently a personal manifesto of rebellion against the poetical taste of the day. The key-note of that much-discussed volume was a mutinous one; on the ethical, the religious, and the purely literary sides it was essentially revolutionary and provocative.

The general public and the reviewers, outraged in their dearest convictions, sought a refuge in an indignant reproof of “the overpassionate sensuousness” of Poems and Ballads. It was treated so vehemently as a work of unseemly tendency, as an incentive to dissolute conduct, that a certain stigma of practical immorality has rested upon it ever since. But although this view was very loftily presented by the moralists of 1866, it was founded less upon fact than upon terror and prejudice. It was only so far true as it is true to say that any reference to certain sexual aberrations may tend to immorality. But what the poet was actually engaged in projecting was a reaction not against the morals but against the æsthetic authorities of the hour, with the design of replacing them by a wider range of intellectual interests, a warmer glow of imagination, and a more spirited exercise of executive skill.

The result of contemplating “Dora” to excess was to create a curiosity as to the case of “Anactoria.” Alike in the classic, the mediæval, and the biblical subjects of which Poems and Ballads treat, the moral or immoral significance of the poet’s statement was very slight in comparison with the artistic passion which he exercised in making it, his object being in all cases beauty, and nothing but beauty, even where the subject might seem to demand a reprobation which it was none of his business to supply.

He presented a new ideal of poetry, in defiance of the mid-Victorian Muses:

“Ah the singing, ah the delight, the passion!

All the Loves wept, listening; sick with anguish,

Stood the crowned nine Muses about Apollo;

Fear was upon them,

While the tenth sang wonderful things they knew not.”

Well satisfied with the effect of his ethical lyrics, Swinburne turned to the transcendental study of politics; or rather, he now concentrated for some years upon this subject elements which had long existed side by side with his analysis of passion. We must go back to 1849, when the extraordinary little boy, as he read the Italian newspapers in the College library at Eton, perceived Mazzini entering Florence in triumph and proclaiming the short-lived Republic of Tuscany. From that deceptive moment, from that flash in the cloud, the eyes of Algernon Swinburne were riveted upon the deliverer of Italy.

It was to be long before the worship of Swinburne for Mazzini was to become articulate, but it continued to intensify, while the irritation against kings and priests grew more and more violent, until the full volume and vehemence of it was poured out upon the world in the Songs before Sunrise of 1871. The revolutionary aspirations of which Swinburne made himself the trumpet were mainly those of one country, and that not his own; he was practically the mouthpiece of what he called “Italia, the world’s wonder, the world’s care.”

This would greatly restrict our final interest in the collection of poems, were it not that the poet combined with his fury for Italian revolution a whole system of philosophical considerations. These were so original and profound that they must always give such pieces as Hertha and Tiresias and the Prelude a permanent value not to be measured in terms of Aspromonte or Mentana. The emotion of the poet in presence of the supreme and eternal characteristics of the universe gives to the noblest parts of Songs before Sunrise an unparalleled intensity. But, meanwhile, in several dramas, of which Atalanta in Calydon and Chastelard are the most important, Swinburne had shown himself desirous to compete with the great playwrights of Athens and of Elizabeth. These chamber-plays were diversified with enchanting lyrics, but they are mainly composed in a highly competent and suave blank verse, the merit of which, however, does not prevent our missing something of the burning colour and vehement motion of the wholly lyrical volumes.

Swinburne was never weary of the dramatic form, and he continued to cultivate it to the very close of his life. The dozen plays which are enrolled in the list of his writings do not exhaust the tale of his dramatic experiments. Among them all Bothwell stands out as theatrically the most successful; it approaches near to our conception of what a vast theatrical romance should be, and the characters in it are built up with great solicitude and deliberation.

Of the choral plays Erechtheus, though it can never enjoy the popularity of Atalanta, has a majesty of ceremonial perfection hardly to be sought elsewhere in English literature. But Swinburne, in spite of all his effort, remains a lyrical poet who crowded an imaginary stage with historical and literary rather than histrionic conceptions.

If he was never wholly successful in drama, he was still less so in narrative. He had no faculty for telling a story either in prose or in verse, and in this he is much inferior not only to William Morris, but even to D. G. Rossetti. Swinburne, however, was persistently anxious to excel in this direction, and by dint of immense labour he completed a romantic epic, Tristram of Lyonesse, which he hoped would be the crowning triumph of his career. In spite, however, of passages of extreme beauty — all of them of the lyrical order — Tristram was found to possess the fatal fault of making no progress in the telling of its tale. In the phrase of Marvell, the reader of it exclaims:—

- “Stumbling on melons, as I pass,

- Ensnared with flowers, I fall on grass,”

the complication and excess of ornament positively choking the progress of the narrative. If Tristram of Lyonesse, however, is a splendid failure, it is important as illustrating a side of Swinburne’s poetry which is of great importance, his passion for and intimate knowledge of the sea. Like the child in "Thalassius" (a consciously autobiographical poem),

“The soul of [Swinburne’s] senses felt

The passionate pride of deep-sea pulses….

And with his heart

The tidal throb of all the tides kept rhyme.”

The only physical exercises in which at any time of his life he took pleasure were riding and swimming, each of which ministered to his craving for rapid and impetuous movement. He is like a swimmer and a rider in his dithyrambic melodies, and there is an intimate connexion between the vehemence of his poetry and his delight in headlong exercise. But in his continuous passion for and cultivation of the sea there is more than this.

When he was in middle life, and his bodily fire had much decayed, he wrote, in a private letter, "As for the sea, its salt must have been in my blood before I was born.... It shows the truth of my endless passionate returns to the sea in all my verse." No one, indeed, has ever questioned either the sincerity or the felicity of the constant allusions to the sea which animate, with a marvellous variety, almost every work which Swinburne has signed.

In this he surpasses all other poets, for they have celebrated deeds on ships or the life of the maritime profession, but Swinburne more than any of them has dealt with the various moods, appearances, and voices of the element itself. In particular he has introduced, with magical effect, a new motif into poetry, the physical intoxication of the swimmer, employing it as a symbol of the intense and hazardous progress of the soul through the mystery of experience.

It does not lead us far to inquire, with the critics of forty years ago, what Swinburne owes to Greece and France and Northumberland, or to trace in him evidences of the influence of Baudelaire or Shelley, of Marlowe or of Victor Hugo. We grant that this great musician was of the composite order, that his genius was built up with precious materials for which he had ransacked the ages. But he melted these materials in a fire of intellectual passion hotter than that possessed by any of his contemporaries, and he applied the result explosively to the poetical conventions of his youth.

He compelled the world at large to take a more exalted view than it ever had taken of the heritage of the past, and he added to that treasure a magnificent contribution of his own. He was a disinterested enthusiast, and Beauty was never celebrated in purer or more rapturous music.[12]

Recognition[]

Swinburne was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in every year from 1903 to 1907 and again in 1909.[13]

4 of his poems ("Chorus from 'Atalanta'," "Hertha," "Ave atque Vale," and "Itylus") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[14]

The authentic portraits of Swinburne are not very numerous: D.G. Rossetti made a pencil drawing in 1860, and in 1862 a water-color painting, an excellent portrait; a bust in oils, by G.F. Watts, May 1867, now in the National Portrait Gallery (as a likeness this is very unsatisfactory); water-color drawing (circa 1863) by Simeon Solomon, which has disappeared. Miss E.M. Sewell made a small drawing in 1868; a water-color, by W.B. Scott (circa 1860); a large pastel, taken in old age (Jan. 1900), by R. Ponsonby Staples. A full-length portrait in water-colour was painted by A. Pellegrini ("Ape") for reproduction in Vanity Fair in the summer of 1874; this drawing, although avowedly a caricature, is in many ways the best surviving record of Swinburne's general aspect and attitude.[7]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Atalanta in Calydon. (verse drama; illustrated by D.G. Rossetti). London: Moxon, 1865; Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866.

- Poems and Ballads. London: Moxon, 1866.

- published in U.S. as Laus Veneris, and other poems and ballads. New York: Carleton, 1866.

- A Song of Italy. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867.

- Songs before Sunrise. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1871.

- Songs of Two Nations. London: Chatto & Windus, 1875.

- Studies in Song. London: Chatto & Windus, 1880.[15]

- Poems and Ballads: Second series. London: Chatto & Windus, 1878. New York: Crowell, ca. 1885.

- Specimens of Modern Poets: The Heptalogia; or, The seven against sense. London: Chatto & Windus, 1880.

- Tristam of Lyonesse, and other poems. London: Chatto & Windus, 1882; Portland, ME: Mosher, 1904.

- A Century of Roundels. New York: Worthington, 1883.

- A Midsummer Holiday, and other poems. London: Chatto & Windus, 1884.

- Poems and Ballads: Third series. London: Chatto & Windus, 1889.

- Selections from the Poetical Works. London: Chatto & Windus, 1889.[16]

- Songs of the Springtides. London: Chatto & Windus 1891.[17]

- Astrophel, and other poems. London: Chatto & Windus; New York: Scribner, 1894.

- The Tale of Balen. New York: Scribner, 1896.

- Robert Burns. A poem. Edinburgh: Burns Centenary, 1896.

- A Word for the Navy. London: George Redway, 1896.

- Poems and Ballads: Second & third series. Portland, ME: Mosher, 1902.

- A Channel Passage, and other poems. London: Chatto & Windus, 1904.

- Poems. (6 volumes), London: Chatto & Windus, 1904; (6 volumes), New York: Harper, 1904. Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, Volume 5, Volume 6.

- Anactoria, and other lyrical poems. New York: M. Kennerley, 1906.[18]

- The Marriage of Monna Lisa. London: privately printed, 1909.

- In the Twilight. London: privately printed, 1909.

- The Portrait. London: privately printed, 1909.

- The Chronicle of Queen Fredegond. London: privately printed, 1909.

- Of Liberty and Loyalty. London: privately printed, 1909.

- Ode to Mazzini. London: privately printed, 1909.

- The Ballade of Truthful Charles, and other poems. London: privately printed, 1910.

- The Ballade of Villon and Fat Madge. London: privately printed, 1910.

- Border Ballads. Boston: Bibliophile Society, 1912.

- Lady Maisie's Bairn and other poems. London: privately printed, 1915.

- Poems from "Villon", and other fragments. London: privately printed, 1916.

- Poetical Fragments. London: privately printed, 1916.

- Posthumous Poems'' (edited by Edmund Gosse and Thomas James Wise). London: Heinemann, 1917.

- Rondeaux Parisiens. London: privately printed, 1917.

- The Italian Mother, and other poems. London: privately printed, 1918.

- The Ride from Milan, and other poems. London: privately printed, 1918.

- A Lay of Lilies, and other poems. London: privately printed, 1918.

- Queen Yseult, A poem in six cantos. London: privately printed, 1918.

- Lancelot, The death of Rudel, and other poems. London: privately printed, 1918.

- Undergraduate Sonnets. London: privately printed, 1918.

- French Lyrics. London: privately printed, 1919.

- Ballads of the English Border (edited by William A. MacInnes). London: Heinemann, 1925.

Plays[]

- The Queen-Mother and Rosamond: Two plays. Pickering, 1860; Boston: Ticknor Fields, 1866.

- Chastelard. London: Moxon, 1865; New York: Hurd Houghton, 1866.

- Bothwell: A tragedy. London: Chatto & Windus, 1874.[19]

- Erechtheus: A tragedy. London: Chatto & Windus, 1876.

- Mary Stuart. New York: Worthington, 1881.

- Marino Faliero. London: Chatto & Windus, 1885.

- Locrine: A tragedy. New York: Alden, 1887.

- The Sisters: A tragedy. New York:, United States Book Company, 1892.

- Rosamund, Queen of the Lombards: A tragedy, Dodd, 1899.

- The Tragedies of Algernon Charles Swinburne. (5 volumes), London: Chatto & Windus, 1906; New York: Harper, 1906.[20] Volume I, Volume II, Volume III, Volume IV, Volume V.

- The Duke of Gandia. New York: Harper, 1908.

- A Criminal Case. London: privately printed, 1910.

- The Cannibal Catechism. London: privately printed, 1913.

- Felicien Cossu: A Burlesque. London: privately printed, 1915.

- Theophile. London: privately printed, 1915.

- Ernest Clouet. London: privately printed, 1916.

- A Vision of Bags. London: privately printed, 1916.

- The Death of Sir John Franklin. London: privately printed, 1916.

- The Queen's Tragedy. London: privately printed, 1919.

Novels[]

- Love's Cross-Currents: A year's letters (novel). Portland, ME: Mosher, 1901; London: Chatto & Windus, 1905.

- Lesbia Brandon (edited by Randoph Hughes). London: Falcon Press, 1952,

- The Novels of A.C. Swinburne. Farrar, Straus Cudahy, 1962.

Short fiction[]

- Les Fleurs du Mal, and other stories. London: privately printed, 1913.

Non-fiction[]

- Notes on Poems and Reviews. London: J.C. Hotten, 1866.

- William Blake: A critical essay. London: Hotten, 1868; New York: Dutton, 1906.

- Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition, 1868 (with William Michael Rossetti). London: Hotten, 1868.

- Under the Microscope. London: D. White, 1872; Portland, ME: Mosher, 1899.

- George Chapman: A critical essay. London: Chatto & Windus, 1875.

- Essays and Studies. London: Chatto & Windus, 1875.

- Note of an English Republican on the Muscovite Crusade. London: Chatto & Windus, 1876.

- A Note on Charlotte Bronte. London: Chatto & Windus, 1877.

- A Study of Shakespeare. New York: Worthington, 1880.

- A Study of Victor Hugo. London: Chatto & Windus; New York: Worthington, 1886.

- Miscellanies. London: Chatto & Windus; New York: Worthington, 1886.

- A Study of Ben Jonson. London: Chatto & Windus; New York: Worthington, 1889.

- Studies in Prose and Poetry. London: Chatto & Windus; New York: Scribner, 1894.

- Percy Bysshe Shelley. Philadepphia, PA: Lippincott, 1903.

- Charles Dickens. London: Chatto & Windus, 1913.

- A Pilgrimage of Pleasure: Essays and studies. Boston: R.C. Badger, 1913.[21]

- A Study of Victor Hugo's "Les Miserables,". London: privately printed, 1914.

- Pericles, and other studies. London: privately printed, 1914.

- Thomas Nabbes: A Critical Monograph. London: privately printed, 1914.

- Christopher Marlowe in Relation to Greene, Peele and Lodge. London: privately printed, 1915.

- The Character and Opinions of Dr. Johnson. London: privately printed, 1918.

- Contemporaries of Shakespeare. London: Heinemann, 1919.

On Shakespeare[]

- The Age of Shakespeare. New York: Harper, 1908.

- Shakespeare. London, New York, Toronto, Melbourne: Henry Frowde for Oxford University Press, 1909.

Juvenile[]

- The Springtide of Life: Poems of childhood (edited by Edmund Gosse; illustrated by Arthur Rackham). London: Heinemann, 1918; Toronto: Musson, 1918; Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1918; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1926.[22]

Collected editions[]

- Collected Poetical Works (2 volumes). London: Heinemann, 1924.

- Complete Works (edited by Edmund Gosse & Thomas J. Wise). (20 volumes), London: Heinemann/ Wells, 1925-1927.

- New Writings (edited by Cecil Y. Lang). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1964.

Translated[]

- The Book of François Villon: The little testament and ballads translated into English verse by Algernon Charles Swinburne, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Payne. Boston: International Pocket Library, 1931.[23]

Letters[]

- The Swinburne Letters (edited by Cecil Y. Lang). (6 volumes), New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1962.

- Uncollected Letters (edited by Terry L. Meyers). (3 volumes), London: PIckering & Chatto, 2004.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[24]

See also[]

Algernon Charles Swinburne - Prelude Tristan & Isolde - a poem

Algernon Charles Swinburne "Atalanta in Calydon" Poem animation

A Forsaken Garden Algernon Charles Swinburne Audiobook Short Poetry

- Dolores (Notre-Dame des Sept Douleurs)

- List of British poets

- List of literary critics

- Timeline of British poetry

References[]

Gosse, Edmund (1912). "Swinburne, Algernon Charles". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement. 3. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 456-464.. Wikisource, Web, Mar. 5, 2017.

- Rikky Rooksby, A.C. Swinburne: A poet's life. Aldershot: Scolar, 1997. Press.

- A modern study of his religious attitudes: Margot Kathleen Louis, Swinburne and His Gods: The roots and growth of an agnostic poetry ISBN 0-7735-0715-9

- Jerome McGann, Swinburne: An experiment in criticism (1972) initiated modern Swinburne criticism.

- Robert Peters's Crowns of Apollo

- A.C. Swinburne, Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day (illustrated by Frederick Waddy). London: Tinsley, 1873. Web, Jan. 6, 2011, 48-49.

- Wakeling, E; Hubbard T; Rooksby, R (2008) Lewis Carroll, Robert Louis Stevenson and Algernon Charles Swinburne by their contemporaries. London: Pickering & Chatto, 3 vols.

Fonds[]

- The Swinburne Project: A digital archive of the life and works of Algernon Charles Swinburne. The site includes texts of Swinburne's works as well as letters and other material supplemental to Meyers, Uncollected Letters (above).

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 John William Cousin, "Swinburne, Algernon Charles," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 368-369. Wikisource, Web, Mar. 10, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gosse (1912), 456.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Gosse (1912), 457.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 Gosse (1912), 458.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Gosse (1912), 459.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 Gosse (1912), 463.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Gosse (1912), 464.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Gosse (1912), 460.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 Gosse (1912), 461.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 Gosse (1912), 462.

- ↑ A.C. Swinburne: Biography

- ↑ from Edmund W. Gosse, "Critical Introduction: Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Algernon Charles Swinburne". The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Literature, 1901-1950. Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/nomination/nomination.php?action=advsearch&start=11&key1=candcountry&log1==&string1=GB&log10=&log11=&order1=year&order2=nomname&order3=cand1name. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ Alphabetical list of authors: Shelley, Percy Bysshe to Yeats, William Butler, Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 19, 2012.

- ↑ Studies in Song by Algernon Charles Swinburne, Project Gutenberg, July 28, 2012.

- ↑ [selectionsfromposwin Selections from the Poetical Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1889)], Internet Archive, Web, July 28, 2012.

- ↑ Songs of the Springtides (1891), Internet Archive, July 28, 2012.

- ↑ Anactoria, and other lyrical poems (1906), Internet Archive, Web, July 28, 2012.

- ↑ Bothwell: a tragedy (1874), Internet Archive, Web, July 28, 2012.

- ↑ The Tragedies of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1906), Internet Archive. Web, Nov. 26, 2013.

- ↑ A Pilgrimage of Pleasure: essays and studies (1913), Internet Archive, Web, July 28, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Algernon Charles Swinburne, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Apr. 30, 2022.

- ↑ Search results = au:JOhn Payne 1842-1916, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Oct. 20, 2013.

- ↑ Algernon Charles Swinburne 1837-1909, Poetry Foundation, Web, July 28, 2012.

External links[]

- Poems

- 4 poems by Swinburne: "March: An ode," "When the Hounds of Spring," "August," "Hendecasyllabics"

- Algernon Charles Swinburne 1837-1909 at the Poetry Foundation

- Swinburne in the Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse: "Hertha," "A Nympholept"

- Algernon Charles Swinburne in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900: "Chorus from 'Atalanta'," "Hertha," "Ave atque Vale," and "Itylus"

- Swinburne in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "A Match," "Hesperia," "In Memory of Walter Savage Landor," "Love at Sea," from Rosamond, from Chastelard, from Bothwell, "Sapphot," "Hope and Fear," "On the Deaths of Thomas Carlyle and George Eliot," "Hertha," "Étude Réaliste," "The Roundel," "A Forsaken Garden," "On the Monument Erected to Mazzini at Genoa"

- from Atalanta in Calydon: I. Chorus, "When the Hounds of Spring", from the Chorus, "We Have Seen Thee, O Love",

- Swnburne in The English Poets: An anthology: Extract from Erechtheus: Chthonia to Athens, "A Forsaken Garden," From "Pan and Thalassius", "A Reiver's Neck-Verse"

- Extracts from Atalanta in Calydon: Chorus: "When the hounds of spring are on winter’s traces", Chorus: "Before the beginning of years", Itylus, A Match, From the Triumph of Time, Rococo, In Memory of Walter Savage Landor, The Garden of Proserpine, Love at Sea, Hendecasyllabics