No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

===Poetry=== |

===Poetry=== |

||

*''Poems''. New York; John W. Lovell, 1848; [https://archive.org/details/poems01king 2nd edition], Boston: [[Ticknor & Fields]], 1856. |

*''Poems''. New York; John W. Lovell, 1848; [https://archive.org/details/poems01king 2nd edition], Boston: [[Ticknor & Fields]], 1856. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11064 Andromeda, and other poems]''. London: John W. Parker, 1858; Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1858. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/poemscha00kingiala Poems]''. London & New York: [[Macmillan Publishers|Macmillan]], 1889. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/poemscha00kingiala Poems]''. London & New York: [[Macmillan Publishers|Macmillan]], 1889. |

||

*''[https://archive.org/details/cu31924013492594 The Poems of Charles Kingsley]''. London & Oxford, UK: [[Oxford University Press]]; London & Toronto: [[J.M. Dent]] / New York: [[E.P. Dutton]], 1913. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/cu31924013492594 The Poems of Charles Kingsley]''. London & Oxford, UK: [[Oxford University Press]]; London & Toronto: [[J.M. Dent]] / New York: [[E.P. Dutton]], 1913. |

||

===Plays=== |

===Plays=== |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11346 The Saint's Tragedy]''. London: John W. Parker, 1848. |

===Novels=== |

===Novels=== |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8374 Alton Locke, Tailor and Poet: An autobiography]''. London: [[Chapman & Hall]], 1850; New York: A.L. Burt, 1850. ''[https://archive.org/details/herewardlasteng01kinggoog Volume I], Volume II'' |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10364 Yeast: A problem]''. London: Nelson, 1851; New York: Harper, 1851. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/6308 Hypatia; or, New foes with an old face]''. London: John W. Parker, 1853. [https://archive.org/details/novelspoemsandl12kinggoog Volume I], Volume II |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1860 Westward Ho!]''.London: Nelson, 1855; New York: A.L. Burt, 1855; Chicago: Hooper, Clarke, 1855. |

| − | * |

+ | *''Two Years Ago'' (a novel). (2 volumes), Cambridge, UK: [[Macmillan Publishers|Macmillan]], 1857; Boston: [[Ticknor & Fields]], 1857. ''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10920 Volume I], [http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10995 Volume II]''. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7815 Hereward the Wake: "last of the English"]'', a novel. London & Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1866. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/tutorsstoryunpub00kinguoft The Tutor's Story: An unpublished novel]''. London: [[Smith, Elder]], 1916; New York: [[Dodd, Mead & Co.|Dodd, Mead]], 1916; Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1916. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/tutorsstoryunpub00kinguoft The Tutor's Story: An unpublished novel]''. London: [[Smith, Elder]], 1916; New York: [[Dodd, Mead & Co.|Dodd, Mead]], 1916; Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1916. |

||

===Non-fiction=== |

===Non-fiction=== |

||

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7954 Twenty-five Village Sermons]''. London: John W. Parker, 1849; Philadelphia: H. Hooker, 1854. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7954 Twenty-five Village Sermons]''. London: John W. Parker, 1849; Philadelphia: H. Hooker, 1854. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''Cheap Clothes and Nasty''. London: William Pickering, 1850. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11025 Phaeton, or Loose Thoughts for Loose Thinkers]''. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1852; Philadelphia: Herman Hooker, 1854. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11025 Phaeton, or Loose Thoughts for Loose Thinkers]''. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1852; Philadelphia: Herman Hooker, 1854. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8202 Sermons on National Subjects]''. London: Richard Griffin, 1854. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/695 Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore]''. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1855. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1275 Alexandria and her Schools: Four lectures delivered at the Philosophical Institution]''. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1854. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11381 Sermons for the Times]''. London: J.W. Parker, 1855. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7051 The Good News of God: Sermons]''. London: J.W. Parker, 1859; New York: Burt, Hutchinson, & Abbey, 1859. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3143 Sir Walter Raleigh and His Time], with other papers''. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1859. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3143 Sir Walter Raleigh and His Time], with other papers''. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1859. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''Miscellanies''. (2 volumes), London: John W. Parker, 1859. ''[https://archive.org/details/miscellanies01kingiala Volume I], [https://archive.org/details/miscellanies02kingiala Volume II]''. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[https://archive.org/details/a589092200kinguoft The Limits of Exact Science applied to History: An inaugural lecture, delivered before the University of Cambridge]''. Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1860. |

*''[http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000484476 New Miscellanies]''. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860. |

*''[http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000484476 New Miscellanies]''. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11536 Town and Country Sermons]''. London: Parker, Son & Bourn, 1861. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10325 The Gospel of the Pentateuch: A set of parish sermons]''. London: Parker, Son, & Bourn, 1863. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3821 The Roman and the Teuton: A series of lectures delivered before the University of Cambridge].'' Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1864. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10326 David, and other sermons]''. Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1865. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1335 Three Lectures delivered at the Royal Institution, on The Ancient Régime]''.London: Macmillan, 1867. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5687 The Water of Life, and other sermons]''. London: Macmillan, 1867; Philadelphia: [[J.B. Lippincott]], 1868. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7042 Discipline, and other sermons]''. London: Macmillan, 1868. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7042 Discipline, and other sermons]''. London: Macmillan, 1868. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8733 The Hermits']''. London: Macmillan, 1868; Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1868. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20433 Women and Politics]''. London: London National Society for Women's Suffrage, 1869. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20433 Women and Politics]''. London: London National Society for Women's Suffrage, 1869. |

||

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10669 At Last: a Christmas in the West Indies]''. London & New York: Macmillan, 1871; New York: Harper, 1871. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10669 At Last: a Christmas in the West Indies]''. London & New York: Macmillan, 1871; New York: Harper, 1871. |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''Sermons on National Subjects: Second series''. London: Macmillan, 1872. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10251 Town Geology]''. London: Strahan, 1872; New York: [[D. Appleton & Co.|D. Appleton]], 1873. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7042 Discipline, and other sermons]'' (1872) |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7032 Prose Idylls, new and old]''. London: Macmillan, 1873. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3142 Plays and Puritans, and other historical essays]''. London: Macmillan, 1873, |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17437 Health and Education]''. London: W. Isbister, 1874; New York: D. Appleton, 1874. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/18369 Westminster Sermons]''. London & New York: Macmillan, 1874. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/30944 Lectures delivered in America in 1874]''. London: [[Longman|Longmans, Green]], 1875; Philadelphia: Coates, 1875. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/villagesermonsto00kingrich Village Sermons, and Town and country sermons]''. London: Macmillan, 1877; London & New York: Macmillan, 1879. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/villagesermonsto00kingrich Village Sermons, and Town and country sermons]''. London: Macmillan, 1877; London & New York: Macmillan, 1879. |

||

*''[https://archive.org/details/cu31924007506177 All Saints Day, and other sermons]''. London: C. Kegan Paul, 1878. |

*''[https://archive.org/details/cu31924007506177 All Saints Day, and other sermons]''. London: C. Kegan Paul, 1878. |

||

| Line 290: | Line 290: | ||

===Juvenile=== |

===Juvenile=== |

||

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/677 The Heroes; or, Greek fairy tales for my children]''. London: Blackie, 1855. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/36309 The Water-Babies: A fairy tale for a land baby]''. London: Ward, Lock, 1863; London & New York: Nelson, 1863; London: [[J.M. Dent]], 1957. |

| − | * |

+ | *''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1697 Madam How and Lady Why; or, First lessons in earth lore for children]''. London: [[George Bell|Bell & Daldy]], 1870. |

=== Collected editions=== |

=== Collected editions=== |

||

| − | *'' |

+ | *''Works''. London: Macmillan, 1878. |

*''Masterpieces from Charles Kingsley''. Philadelphia: Rodgers, 1890. |

*''Masterpieces from Charles Kingsley''. Philadelphia: Rodgers, 1890. |

||

*''Selections from Some of the Writings of Charles Kingsley''. London: Macmillan, 1884. |

*''Selections from Some of the Writings of Charles Kingsley''. London: Macmillan, 1884. |

||

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20711 Daily Thoughts: Selected from the writings of Charles Kingsley by his wife]'' (selected by Frances Eliza Grenfell Kingsley). London & New York: Macmillan, 1884. |

*''[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20711 Daily Thoughts: Selected from the writings of Charles Kingsley by his wife]'' (selected by Frances Eliza Grenfell Kingsley). London & New York: Macmillan, 1884. |

||

| − | *'' |

+ | *''Novels and Poems''. New York: J.F. Taylor, 1898. |

| − | *''Novels, Poems, and Letters |

+ | *''Novels, Poems, and Letters''. New York & London: Co-operative Publication Society, 1898-1899. ''Volume I, [http://archive.org/details/novelspoemsandl03kinggoog Volume II], [http://archive.org/details/herewardlasteng01kinggoog Volume III], Volume IV, Volume V, [http://archive.org/details/novelspoemsandl12kinggoog Volume VI], Volume VII, [http://archive.org/details/novelspoemsandl00kinggoog Volume VIII], Volume IX, Volume X'' |

*''The Pocket Charles Kingsley''. London: [[Chatto & Windus]], 1907. |

*''The Pocket Charles Kingsley''. London: [[Chatto & Windus]], 1907. |

||

| Line 309: | Line 309: | ||

<small>''Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy [[WorldCat]]''</small>.<ref>[http://www.worldcat.org/search?q=au%3ACharles+Kingsley&fq=&dblist=638 Search results = au:Charles Kingsley], WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Sep. 13, 2013.</ref> |

<small>''Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy [[WorldCat]]''</small>.<ref>[http://www.worldcat.org/search?q=au%3ACharles+Kingsley&fq=&dblist=638 Search results = au:Charles Kingsley], WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Sep. 13, 2013.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Young And Old a poem by Charles Kingsley|thumb|right|335 px]] |

[[File:Young And Old a poem by Charles Kingsley|thumb|right|335 px]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:The Dead Church a poem written by Charles Kingsley|thumb|right|335 px]] |

[[File:The Dead Church a poem written by Charles Kingsley|thumb|right|335 px]] |

||

*[[List of British poets]] |

*[[List of British poets]] |

||

| Line 332: | Line 332: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

; Poems |

; Poems |

||

| − | * |

+ | *"[http://gdancesbetty.blogspot.ca/2012/09/drifting-away.html Drifting Away: A Fragment]" |

| − | * |

+ | *Charles Kingsley in the ''Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900:'' "[http://www.bartleby.com/101/739.html "Airly Beacon"], [http://www.bartleby.com/101/740.html "The Sands of Dee"] |

| − | * |

+ | *[http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poets/kingsley-charles Kingsley, Charles (1819-1875)] (5 poems) at [[Representative Poetry Online]] |

*Kingsley in ''The English Poets: An anthology:'' [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1197.html Pallas in Olympus (from ''Andromeda''], "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1198.html The Last Buccaneer], [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1199.html The Sands of Dee (from ''Alton Loch'')]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1200.html A Farewell]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1201.html Dolcino to Margaret]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1202.html Airly Beacon]," [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1203.html A Boat-Song (from ''Hypatia'')], [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1204.html The Song of Madame Do-as-you-would-be-done-by (from ''The Water Babies'')], "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1205.html The 'Old, Old Song']" |

*Kingsley in ''The English Poets: An anthology:'' [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1197.html Pallas in Olympus (from ''Andromeda''], "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1198.html The Last Buccaneer], [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1199.html The Sands of Dee (from ''Alton Loch'')]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1200.html A Farewell]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1201.html Dolcino to Margaret]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1202.html Airly Beacon]," [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1203.html A Boat-Song (from ''Hypatia'')], [http://www.bartleby.com/337/1204.html The Song of Madame Do-as-you-would-be-done-by (from ''The Water Babies'')], "[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1205.html The 'Old, Old Song']" |

||

*Kingsley in ''[[A Victorian Anthology]]:'' [http://www.bartleby.com/246/570.html from ''The Saint's Tragedy''], "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/571.html The Sands of Dee]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/572.html The Three Fishers]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/573.html A Myth]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/574.html The Dead Church]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/575.html Anromeda and the Sea-Nymphs]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/576.html The Last Buccaneer]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/577.html Lorraine]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/578.html A Farewell]" |

*Kingsley in ''[[A Victorian Anthology]]:'' [http://www.bartleby.com/246/570.html from ''The Saint's Tragedy''], "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/571.html The Sands of Dee]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/572.html The Three Fishers]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/573.html A Myth]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/574.html The Dead Church]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/575.html Anromeda and the Sea-Nymphs]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/576.html The Last Buccaneer]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/577.html Lorraine]," "[http://www.bartleby.com/246/578.html A Farewell]" |

||

| − | * |

+ | *[http://theotherpages.org/poems/poem-kl.html#kingsley Index entry for Charles Kingsley] at [[Poets' Corner (website)|Poets' Corner]] |

*[http://www.poemhunter.com/charles-kingsley/ Charles Kingsley] at [[PoemHunter]] (86 poems) |

*[http://www.poemhunter.com/charles-kingsley/ Charles Kingsley] at [[PoemHunter]] (86 poems) |

||

*[http://www.poetrynook.com/poet/charles-kingsley Charles Kingsley] at Poetry Nook (131 poems) |

*[http://www.poetrynook.com/poet/charles-kingsley Charles Kingsley] at Poetry Nook (131 poems) |

||

| Line 343: | Line 343: | ||

*[https://www.google.ca/#q=charles+kingsley+poems+youtube Charles Kingsley] poems at [[YouTube]] |

*[https://www.google.ca/#q=charles+kingsley+poems+youtube Charles Kingsley] poems at [[YouTube]] |

||

;Books |

;Books |

||

| − | * |

+ | *{{gutenberg author|name=Charles Kingsley|id=Charles_Kingsley}} (plain text and HTML) |

*[http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=creator%3AKingsley%2C%20Charles%20-contributor%3Agutenberg%20AND%20mediatype%3Atexts Works by Charles Kingsley] at [[Internet Archive]] |

*[http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=creator%3AKingsley%2C%20Charles%20-contributor%3Agutenberg%20AND%20mediatype%3Atexts Works by Charles Kingsley] at [[Internet Archive]] |

||

*[http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Kingsley%2C%20Charles%2C%201819-1875 Charles Kingsley] at the [[Online Books Page]] |

*[http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Kingsley%2C%20Charles%2C%201819-1875 Charles Kingsley] at the [[Online Books Page]] |

||

| Line 351: | Line 351: | ||

*[http://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Kingsley Charles Kingsley] in the ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]'' |

*[http://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Kingsley Charles Kingsley] in the ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]'' |

||

*[https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Kingsley,_Charles Kingsley, Charles] in the [[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition|1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'']] |

*[https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Kingsley,_Charles Kingsley, Charles] in the [[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition|1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'']] |

||

| − | * |

+ | *Frederick Waddy, "[http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cartoon_portraits_and_biographical_sketches_of_men_of_the_day/Canon_Kingsley "Canon Kingsley]," ''Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day'' (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1873) |

| − | *[http://www.bartleby.com/337/1196.html Critical Introduction] by [[William Ernest Henley]] |

||

{{DNB}} [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Kingsley,_Charles_(DNB00) Kingsley, Charles] |

{{DNB}} [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Kingsley,_Charles_(DNB00) Kingsley, Charles] |

||

Latest revision as of 21:17, 10 August 2020

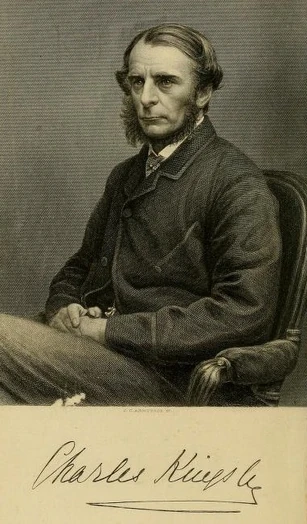

Charles Kingsley (1819-1875), from Charles Kingsley: His letters, and memories of his life, 1877. Courtesy Internet Archive.

| Charles Kingsley | |

|---|---|

| Born |

June 12 1819 Holne, Devon, England |

| Died |

January 23 1875 (aged 55) Eversley, Hampshire, England |

| Occupation | Clergyman, University professor, Historian, Writer (novelist) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Cambridge University |

| Period | 19th century |

| Genres | novels, poetry, children's literature |

Rev. Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 - 23 January 1875) was a priest of the Church of England and an English poet, academic, historian, and novelist, particularly associated with the West Country and northeast Hampshire.

Life[]

Overview[]

Kingsley, son of a clergyman, was born at Holne Vicarage near Dartmoor, but passed most of his childhood at Barnack in the Fen country, and Clovelly in Devonshire, and educated at King's College, London, and Cambridge. Intended for the law, he entered the Church, and became, in 1842, curate, and 2 years later rector, of Eversley, Hampshire. In the latter year he published The Saints' Tragedy, a drama, of which the heroine is St. Elizabeth of Hungary. 2 novels followed, Yeast (1848) and Alton Locke (1850), in which he deals with social questions as affecting the agricultural labouring class and the town worker respectively. He had become deeply interested in such questions, and threw himself heart and soul, in conjunction with F.D. Maurice and others, into the schemes of social amelioration, which they supported under the name of Christian socialism, contributing many tracts and articles under the signature of "Parson Lot." In 1853 appeared Hypatia, in which the conflict of the early Christians with the Greek philosophy of Alexandria is depicted; it was followed in 1855 by Westward Ho!, perhaps his most popular work; in 1857 by Two Years Ago, and in 1866 by Hereward the Wake. At Last (1870), gave his impressions of a visit to the West Indies. His taste for natural history found expression in Glaucus; or, The wonders of the shore (1855), and other works. The Water Babies is a story for children written to inspire love and reverence of Nature. Kingsley was in 1860 appointed to the Professorship of Modern History at Cambridge, which he held until 1869. The literary fruit of this was Roman and Teuton (1864). In the same year he was involved in a controversy with J.H. Newman, which resulted in the publication by the latter of his Apologia. Kingsley, who had in 1869 been made a Canon of Chester, became Canon of Westminster in 1873. Always of a highly nervous temperament, his over-exertion resulted in repeated failures of health, and he died in 1875. Though hot-tempered and combative, he was a man of singularly noble character. His type of religion, cheerful and robust, was described as "muscular Christianity." Strenuous, eager, and keen in feeling, he was not either a profoundly learned, or perhaps very impartial, historian, but all his writings are marked by a bracing and manly atmosphere, intense sympathy, and great descriptive power.[1]

Youth and education[]

Kingsley was born at Holne Vicarage, Devonshire, son of the Rev. Charles Kingsley by his wife, daughter of Nathan Lucas of Barbadoes and Rushford Lodge, Norfolk. His father (died 1860) had been bred as a country gentleman; but, from the carelessness of his guardians during a long minority, had been forced to adopt a profession, and had taken orders after 30. He took a curacy in the fens, and afterwards at Holne, whence he moved to Burton-on-Trent and Clifton in Nottinghamshire. He held the valuable living of Barnack in Northamptonshire (between Peterborough and Stamford) from 1824 to 1830, until the son of Bishop Marsh could take orders. He caught ague in the fen country, and was advised to remove to Devonshire, where he was presented to Clovelly. He remained there till, in 1836, he became rector of St. Luke's, Chelsea.[2]

Charles was a precocious child, writing sermons and poems at the age of 4. He was delicate and sensitive, and retained through life the impressions made upon him by the scenery of the fens and of Clovelly. At Clovelly he learnt to boat, to ride, and to collect shells.[2]

In 1831 he was sent to a school at Clifton, and saw the Bristol riots of August 1831, which he says for some years made him a thorough aristocrat. In 1832 he was sent to the grammar school at Helston, Cornwall, then under Derwent Coleridge. Kingsley was not a close student, though he showed great intellectual activity. He was not popular, rather despising his fellows, caring little for the regular games, although fond of feats of agility and of long excursions in search of plants and geological specimens. He wrote a good deal of poetry and poetical prose.[2]

In 1836 he went with his family to London, and became a student at King's College, London, walking in and out from Chelsea. He worked hard, but found London life dismal, and was not a little bored by the parish work in which his father and mother were absorbed. He describes the district visitors as ugly and splay-footed beings, "three-fourths of whom can't sing, and the other quarter sing miles out of tune, with voices like love-sick parrots."[2]

In October 1838 he entered Magdalene College, Cambridge, and at the end of his first year gained a scholarship. In the following vacation, while staying with his father in the country, he met, on 6 July 1839, his future wife, Fanny, daughter of Pascoe Grenfell. That, he said afterwards, was "my real wedding-day." They began an occasional correspondence, in which Kingsley confessed very fully to the religious doubts by which he, like others, was tormented at the time of the Oxford movement. He was occasionally so much depressed by these thoughts, and by the uncertainty of any fulfilment of his hopes, that he sometimes thought of leaving Cambridge to "become a wild prairie hunter." His attachment to Miss Grenfell operated as an invaluable restraint.[2]

He read Coleridge, Carlyle, and Maurice with great interest. Meanwhile, though his studies seem to have been rather desultory, he was popular at college, and threw himself into every kind of sport to distract his mind. He rowed, but specially delighted in fishing expeditions into the fens and elsewhere, rode out to Sedgwick's equestrian lectures on geology, and learnt boxing under a negro prize-fighter.[2]

He was a good pedestrian, and once walked to London in a day. His distractions, intellectual, emotional, and athletic, made him regard the regular course of study as a painful drudgery. He read classics with W.H. Bateson, afterwards master of St. John's, during his 1st and 3rd years, but could not be induced to work hard till his last 6 months. He then by great effort succeeded in obtaining the last place in the first class of the classical tripos of 1842. He was a ‘senior optime’ in the previous mathematical tripos.[3]

Early career[]

He had by this time decided to take orders, and in July 1842 was ordained by the Bishop of Winchester to the curacy of Eversley, Hampshire. Eversley is on the borders of Windsor Forest, a wild heather-covered country, with a then neglected population of "broom squires" and deerstealers, and with a considerable infusion of gypsies.[3]

Kingsley disliked the Oxford school, which to him represented sacerdotalism, asceticism, and Manichæism, and was eagerly reading Maurice's Kingdom of Christ. Carlyle and Arnold were also among his prophets. He soon became popular by hard work in his parish and genuine sympathy with the poor, but lived a secluded life, with little society beyond that of a few friends in the Military College at Sandhurst.[3]

A year's interruption in the correspondence with his future wife implies a cause for depression. In September 1843, however, he obtained through one of her relations, Lord Sidney Godolphin Osborne, a promise of a living from Lord Portman, and was advised to apply in the meantime for the curacy of Pimperne, near Blandford. The curacy was promised, and the correspondence was renewed. Early in 1844 he married. The living of Eversley fell vacant at the time, and the parishioners were anxious that he should succeed to it. In May 1844 he was accordingly presented to it by Sir John Cope, the patron, and settled there as rector soon afterwards.[3]

Heavy dilapidations and arrears of poor-rate fell upon the new incumbent; the house was unwholesome, and much drainage was required. The church was empty; no grown-up labourers in the parish could read or write, and everything was in a state of neglect. Kingsley set to work vigorously, and in time successfully, to remedy this state of things. His only recreation was an occasional day's fishing, and sometimes a day with the hounds on an old horse "picked up cheap for parson's work."[3]

In 1844 he made acquaintance with Maurice, to whom he had written for advice upon some of his difficulties. Maurice soon became a revered friend, whom he delighted to call his "master." In 1845 he was appointed a canon of Middleham by Dean Wood, father of an old college friend – a post which was merely honorary, though historically interesting.[3]

In 1842, just after taking his degree, he had begun to write the life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary. He finally changed his original prose into a drama, which was accepted, after some refusals from publishers, by Messrs. Parker, and appeared at the beginning of 1848 with a preface by Maurice. The book excited interest both in Oxford and in Germany. It was much admired by Bunsen, and a review by Conington, though not very favourable, led to a friendship with the critic.[4]

While showing high poetical promise, and indeed containing some of his best work, it is also an exposition of his sentiments upon the social and religious movements of the day. Though expressing sympathy with mediæval life, it is a characteristic protest against the ascetic theories which, as he thought, tended to degrade the doctrine of the marriage bond. The events of 1848 led to a more direct utterance.[4]

Character[]

Kingsley was above middle height, of spare but muscular and vigorous frame, with a strongly marked face, to which the deep lines between the brows gave an expression of sternness. He was troubled by a stammer. He prescribed and practised rules for its cure, but never overcame it in conversation, although in public speaking he could avoid it. The name of "muscular Christianity," first given in the Saturday Review, and some of his verses suggested the tough athlete; but he had a highly nervous temperament, and his characteristic restlessness made it difficult for him to sit still through a meal (Martineau in Kingsley, i. 300).[5]

He had taken to smoking at college to soothe his nerves, and, finding the practice beneficial, acquired the love of tobacco which he expresses in Westward Ho! His impetuous and excitable temper led him to overwork himself from the first, and his early writings gave promise of still higher achievements than he ever produced. The excessive fervour of his emotions caused early exhaustion, and was connected with his obvious weaknesses. He neither thought nor studied systematically, and his beliefs were more matters of instinct than of reason. He was distracted by the wide range and quickness of his sympathy.[5]

He had great powers of enjoyment. He had a passion for the beautiful in art and nature. No one surpassed him in first-hand descriptions of the scenery that he loved. He was enthusiastic in natural history, recognised every country sight and sound, and studied birds, beasts, fishes, and geology with the keenest interest. In theology he was a disciple of Maurice, attracted by the generous feeling and catholic spirit of his master. He called himself a "Platonist" in philosophy, and had a taste for the mystics, liking to recognise a divine symbolism in nature.[5]

At the same time his scientific enthusiasm led him to admire Darwin, Professor Huxley, and Lyell without reserve. He corresponded with J.S. Mill, expressed the strongest admiration of his books, and shared in his desire for the emancipation of women. Certain tendencies of the advocates of women's rights caused him to draw back; but he was always anxious to see women admitted to medical studies. His domestic character was admirable, and he was a most energetic country parson.[5]

He loved and respected the poor, and did his utmost to raise their standard of life. "He was," said Matthew Arnold in a letter of condolence to his family, "the most generous man I have ever known; the most forward to praise what he thought good, the most willing to admire, the most free from all thought of himself, in praising and in admiring, and the most incapable of being made ill-natured or even indifferent by having to support ill-natured attacks himself."[5]

This quality made him attractive to all who met him personally, however averse to some of his views. It went along with a distaste for creeds embodying a narrow and distorted ideal of life—a distaste which biassed his judgment of ecclesiastical matters, and gives the impression that the ancient Greeks or Teutons had more of his real sympathies than the early Christians.[5]

Christian socialist[]

His admiration for Maurice brought about a close association with the group who, with Maurice for leader, were attempting to give a Christian direction to the socialist movement then becoming conspicuous. Among others he came to know A.P. Stanley, Froude, Ludlow, and especially Thomas Hughes, afterwards his most intimate friend.[4]

He was appointed professor of English literature in Queen's College, Harley Street, just founded, with Maurice as president, and gave a course of weekly lectures, though ill-health forced him to give up the post a year later. His work at Eversley prevented him from taking so active a part as some of his friends, but he heartily sympathised with their aims, and was a trusted adviser in their schemes for promoting co-operation and "Christian socialism."[4]

His literary gifts were especially valuable, and his writings were marked by a fervid and genuine enthusiasm on behalf of the poor. He contributed papers to the ‘Politics for the People,’ of which the 1st number (of 17 published) appeared on 6 May 1848. He took the signature "Parson Lot," on account of a discussion with his friends, in which, being in a minority of 1, he had said that he felt like Lot, "when he seemed as one that mocked to his sons-in-law." Under the same name he published a pamphlet called Cheap Clothes and Nasty in 1850, and a good many contributions to the Christian Socialist: A journal of association, which appeared from 2 Nov. 1850 to 28 June 1851. The pamphlet was reprinted with Alton Locke and a preface by Thomas Hughes in 1881.[4]

He produced his first 2 novels under the same influence. Yeast was published in Fraser's Magazine in the autumn of 1848. He had been greatly excited by the events of the previous months, and wrote it at night, after days spent in hard parish work. A complete breakdown of health followed. He went for rest to Bournemouth in October, and after a second collapse spent the winter in North Devon. A further holiday, also spent in Devonshire, became necessary in 1849.[4]

The expenses of sickness and the heavy rates at Eversley tried his finances. He resigned the office of clerk-in-orders at St. Luke's, Chelsea, which he had held since his marriage, but which he now felt to be a sinecure. To make up his income he resolved to take pupils, and by a great effort finished Alton Locke in the winter of 1849–50. Messrs. Parker declined it, thinking that they had suffered in reputation by the publication of Yeast. It was, however, accepted by Chapman & Hall on the recommendation of Carlyle, and appears to have brought the author £150. (Kingsley, i. 277). It was published in August 1850, and was described by Carlyle as a "fervid creation still left half chaotic."[4]

Kingsley's writings exposed him at this time to many and often grossly unfair attacks. In 1851 he preached a sermon in a London church which, with the full knowledge of the incumbent, was to give the views of the Christian socialists, and was called The Message of the Church to the Labouring Man. At the end of the sermon, however, the incumbent rose and protested against its teaching. The press took the matter up, and the Bishop of London (Blomfield) forbade Kingsley to preach in his diocese. A meeting of working-men was held on Kennington Common to support Kingsley. The sermon was printed, and the bishop, after seeing Kingsley, withdrew the prohibition.[4]

The fear of anything called socialism was natural at the time; but Kingsley never adopted the socialist creed in a sense which could now shock the most conservative. In politics he was in later life rather a tory than a radical. He fervently believed in the House of Lords (see e.g. Kingsley, ii. 241–3), detested the Manchester school, and was opposed to most of the radical platform.[4]

He therefore did not sympathise with the truly revolutionary movement, but looked for a remedy of admitted evils to the promotion of co-operation, and to sound sanitary legislation (in which he was always strongly interested). He strove above all to direct popular aspirations by Christian principles, which alone, as he held, could produce true liberty and equality. Thus, when the passions roused in 1848 had cooled down, he ceased to be an active agitator, and became tolerably reconciled to the existing order.[4]

In 1851 he was attacked with gross unfairness or stupidity for the supposed immorality of Yeast, and replied in a letter to the Guardian by a mentiris impudentissime, which showed how deeply he had been stung. He sought relief from worry and work in the autumn of 1851 by his first tour abroad, bringing back from the Rhine impressions afterwards used in Two Years Ago.[4]

One of his private pupils, Mr. John Martineau, has given a very vivid account of his home life at Eversley during this period (Kingsley, i. 297–308). He had brought things into better order, and after his holiday in 1851 was able for some time to work without a curate. Not being able to get another pupil, he was compelled to continue his work single-handed, and again became over-exhausted.[4]

His remarkable novel, Hypatia, certainly 1 of the most successful attempts in a very difficult literary style, appeared in 1853, after passing through Fraser's Magazine. It was well received in Germany as well as England, and highly praised by Bunsen (Memoirs, ii. 309). Maurice took a part in criticising it during its progress, and gave suggestions which Kingsley turned to account.[4]

The winter of 1853-1854 was passed at Torquay for the sake of his wife, whose health had suffered from the damp of Eversley. Here his strong love of natural history led him to a study of seashore objects and to an article on the "Wonders of the Shore" in the North British Review, afterwards developed into Glaucus. In February he gave some lectures at Edinburgh on the Schools of Alexandria, and in the spring settled with his family at Bideford, his wife being still unable to return to Eversley. Here he wrote Westward Ho! It was dedicated to Bishop Selwyn and Rajah Brooke.[4] Brooke was a hero after his own heart, whom he knew personally and had heartily endeavoured to support (Kingsley, i. 222, 369–70, 444–5).[6]

While staying at Bideford Kingsley displayed one of his many gifts by getting up and teaching a drawing class for young men. In the course of 1855 he again settled at Eversley, spending the winter at a house on Farley Hill, for the benefit of his wife's health. Besides frequent lectures, sermons, and articles, he was now writing Two Years Ago, which appeared in 1857.[6]

Kingsley had been deeply interested in the Crimean war. Some thousands of copies of a tract by him called Brave Words to Brave Soldiers, had been distributed to the army. The Crimean pamphlet had been published anonymously, on account of the prejudices against him in the religious world. The prejudices rapidly diminished from this time. In 1859 he became one of the queen's chaplains in ordinary. He was presented to the queen and to the prince consort, for whom he entertained a specially warm admiration. He still felt the strain of overwork, having no curate, and shrank from London bustle, confining himself chiefly to Eversley.[6]

Professor of history[]

In May 1860 he was appointed to the professorship of modern history at Cambridge, vacant by the death in the previous autumn of Sir James Stephen. He took a house at Cambridge, but after 3 years found that the expense of a double establishment was beyond his means, and from 1863 resided at Eversley, only going to Cambridge twice a year to deliver his lectures. During the first period his duties at Eversley were undertaken by the Rev. Septimus Hansard. The salary of the professorship was £371, and the preparation of lectures interfered with other literary work.[6]

During the residence of the Prince of Wales at Cambridge a special class under Kingsley was formed for his benefit, and the prince won the affectionate regard of his teacher. The prince recommended him for an honorary degree at Oxford on the commemoration of 1863, but the threatened opposition of the high church party under Pusey induced Kingsley to retire, with the advice of his friends.[6]

Kingsley's tenure of the professorship can hardly be described as successful. The difficulties were great. The attempt to restore the professorial system had at that time only succeeded in filling the class-rooms with candidates for the ordinary degree. History formed no part of the course of serious students, and the lectures were in the main merely ornamental. Kingsley's geniality, however, won many friends both among the authorities and the undergraduates. Some young men expressed sincere gratitude for the intellectual and moral impulse which they received from him.[6]

Professor Max Müller says (Kingsley, ii. 266) "history was but his text," and his lectures gave the thoughts of "a poet and a moralist, a politician and a theologian, and, above all, a friend and counsellor of young men." They roused interest, but they did not lead to a serious study of history or an elevation of the position held by the study at the university. Kingsley's versatile mind, distracted by a great variety of interests, had caught brilliant glimpses, but had not been practised in systematic study. His lectures, when published, were severely criticised by writers of authority as savouring more of the historical novelist than of the trained inquirer.[6]

He was sensible of this weakness, and towards the end of his tenure of office became anxious to resign. His inability to reside prevented him from keeping up the friendships with young men which, at the beginning of his course, he had rightly regarded as of great value.[6]

Conflict with Newman[]

In the beginning of 1864 Kingsley had an unfortunate controversy with John Henry Newman. He had asserted in a review of Mr. Froude's History in Macmillan's Magazine for January 1864 that "Truth, for its own sake, had never been a virtue with the Roman catholic clergy," and attributed this opinion to Newman in particular.[6]

Upon Newman's protest, a correspondence followed, which was published by Newman (dated 31 Jan. 1864), with a brief, but cutting, comment. Kingsley replied in a pamphlet called What, then, does Dr. Newman mean? which produced Newman's famous Apologia.[6]

Kingsley was clearly both rash in his original statement and unsatisfactory in the apology which he published in Macmillan's Magazine (this is given in the correspondence). That Newman triumphantly vindicated his personal character is also beyond doubt. The best that can be said for Kingsley is that he was aiming at a real blot on the philosophical system of his opponent; but, if so, it must be also allowed that he contrived to confuse the issue, and by obvious misunderstandings to give a complete victory to a powerful antagonist. With all his merits as an imaginative writer, Kingsley never showed any genuine dialectical ability.[7]

Last years[]

Kingsley's health was now showing symptoms of decline. The Water Babies, published in 1863, was, says Mrs. Kingsley, "perhaps the last book, except his West Indian one, that he wrote with any real ease." Rest and change of air had been strongly advised, and in the spring of 1864 he made a short tour in France with Mr. Froude. In 1865 he was forced by further illness to retire for 3 months to the coast of Norfolk.[7]

From 1868 the Rev. William Harrison was his curate, and lightened his work at Eversley. Mr. Harrison contributed some interesting reminiscences to the memoir (Kingsley, ii. 281–8). In 1869 Kingsley resigned his professorship at Cambridge, stating that his brains as well as his purse rendered the step necessary (ib. ii. 293). Relieved from the strain, he gave many lectures and addresses.[7]

He was president of the education section at the Social Science Congress held in October 1869 at Bristol, and delivered an inaugural address, which was printed by the Education League; about 100,000 copies were distributed. He had joined the league, which was generally opposed by the clergy, in despair of otherwise obtaining a national system of education, but withdrew to become a supporter of W.E. Forster's Education Bill. At the end of the year he sailed to the West Indies on the invitation of his friend Sir Arthur Gordon, then governor of Trinidad. His At Last, a graphic description of his travels, appeared in 1870.[7]

In August 1869 Kingsley was appointed canon of Chester, and was installed in November. The next year he began his residence on 1 May, and found congenial society among the cathedral clergy. He started a botany class, which developed into the Chester Natural History Society. He gave some excellent lectures, published in 1872 as Town Geology, and acted as guide to excursions into the country for botanical and geological purposes.[7]

A lecture delivered at Sion College upon the "Theology of the Future" (published in Macmillan's Magazine) stated his views of the relations between scientific theories and theological doctrine, and for the later part of his life his interest in natural history determined a large part of his energy. He came to believe in Darwinism, holding that it was in full accordance with theology. Sanitary science also occupied much of his attention, and an address delivered by him in Birmingham in 1872, as president of the Midland Institute, led to the foundation of classes at the institute and at Saltley College (a place of training for schoolmasters) for the study of the laws of health.[7]

In 1873 he was appointed canon of Westminster, and left Chester, to the general regret of his colleagues and the people. His son, Maurice, had gone to America in 1870, and was there employed as a railway engineer. Returning in 1873, he found his father much changed, and urged a sea-voyage and rest.[7]

At the beginning of 1874 Kingsley sailed for America, was received with the usual American hospitality in the chief cities, and gave some lectures. After a visit to Canada, he went to the west, saw Salt Lake city, San Francisco, the Yosemite valley, and had a severe attack of pleurisy, during which he stayed at Colorado Springs. It weakened him seriously, and after his return in August 1874 he had an attack at Westminster, by which he was further shaken. His wife had a dangerous illness soon afterwards.[7]

He was able to preach at Westminster in November, but was painfully changed in appearance. On 3 Dec. he went with his wife to Eversley, catching fresh cold just before. At Eversley he soon became dangerously ill. His wife was at the same time confined to her room with an illness supposed to be mortal, and he could only send messages for a time. He died peacefully on 23 January 1875.[7]

He was buried at Eversley on 28 January, amid a great concourse of friends, including men of political and military distinction, villagers, and the huntsmen of the pack, with the horses and hounds outside the churchyard. Dean Stanley took part in the service, and preached a funeral sermon in Westminster Abbey (published) on 31 January.[7]

A Civil List pension was granted to Mrs. Kingsley upon her husband's death, but she declined the queen's offer of rooms in Hampton Court Palace.[7] She died at her residence at Bishop's Tachbrook, near Leamington, on Saturday, 12 Dec. 1891, aged 77.[5]

Kingsley's 4 children, all born at Eversley, were: 1. Rose Georgina (b. 1845); 2. Maurice (b. 1847), later of New Rochelle, New York; 3. Mary St. Leger (b. 1852 wife and widow of William Harrison, formerly rector of Clovelly; and 4. Grenville Arthur (b. 1857), later of Queensland. Mrs. Harrison wrote some well-known novels under the pseudonym "Lucas Malet."[5]

Writing[]

Poetry[]

He was a genuine poet, if not of the very highest kind. Some of his stirring lyrics are likely to last long, and his beautiful poem, "Andromeda," is perhaps the best example of the English hexameter.[5]

Novels[]

Yeast and Alton Locke show an even passionate sympathy for the sufferings of the agricultural labourer and of the London artisan. The ballad of the "poacher's widow" in Yeast is a denunciation of game-preservers vigorous enough to satisfy the most thoroughgoing chartist. But Kingsley's sentiment was thoroughly in harmony with the class of squires and country clergymen, who required in his opinion to be roused to their duties, not deprived of their privileges[4].

Like his previous books, Hypatia is intended to convey a lesson for the day, dealing with an analogous period of intellectual fermentation. It shows his brilliant power of constructing a vivid, if not too accurate, picture of a past social state.[4]

Westwrd Ho! is in some ways his most characteristic book, and the descriptions of Devonshire scenery, his hearty sympathy with the Elizabethan heroes, and the unflagging spirit of the story, make the reader indifferent to its obviously one-sided view of history.[6]

He always had keen military tastes; he studied military history with especial interest; many of the officers from Sandhurst and Aldershot became his warm friends; and he delighted in lecturing, preaching, or blessing new colours for the regiments in camp. Such tastes help to explain the view expressed in Two Years Ago, which was then less startling than may now seem possible, that the war was to exercise the great regenerating influence. The novel is much weaker than its predecessors, and shows clearly that if his desire for social reform was not lessened, he had no longer so strong a sense that the times were out of joint. His health and prospects had improved, a result which he naturally attributed to a general improvement of the world.[6]

Other works[]

Kingsley's works are: ‘The Saint's Tragedy,’ 1848. ‘Twenty-five Village Sermons,’ 1849. ‘Alton Locke,’ 1850. ‘Yeast, a Problem,’ 1851 (published in ‘Fraser's Magazine’ in 1848, and cut short to please the proprietors; for intended conclusion see Kingsley, i. 219). ‘Phaethon, or Loose Thoughts for Loose Thinkers,’ 1852. ‘Sermons on National Subjects,’ 1st ser. 1852, 2nd ser. 1854. ‘Hypatia,’ 1853 (from ‘Fraser's Magazine’). ‘Alexandria and her Schools’ (lectures at Edinburgh), 1854. ‘Who causes Pestilence?’ (four sermons), 1854. ‘Sermons for the Times,’ 1855. ‘Westward Ho!’ 1855. ‘Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore,’ 1855. ‘The Heroes, or Greek Fairy Tales,’ 1856. ‘Two Years Ago,’ 1857. ‘Andromeda, and other Poems,’ 1858; ‘Poems’ (1875) includes these and ‘The Saint's Tragedy.’ ‘The Good News of God,’ a volume of sermons, 1859. ‘Miscellanies,’ 1859. ‘Limits of Exact Science, as applied to History’ (inaugural lecture at Cambridge), 1860. ‘Town and Country Sermons,’ 1861. ‘Sermons on the Pentateuch,’ 1863. ‘The Water Babies,’ 1863. ‘David’ (four sermons before the university), 1865. ‘Hereward the Wake,’ 1866. ‘The Ancien Régime’ (three lectures at the Royal Institution), 1867. ‘The Water of Life, and other Sermons,’ 1867. ‘The Hermits’ (Sunday Library, vol. ii.), 1868. ‘Discipline, and other Sermons,’ 1868. ‘Madam How and Lady Why’ (from ‘Good Words for Children’), 1869. ‘At Last: a Christmas in the West Indies,’ 1871. ‘Town Geology’ (lectures at Chester), 1872. ‘Prose Idylls,’ 1873. ‘Plays and Puritans,’ 1873. ‘Health and Education,’ 1874. ‘Westminster Sermons,’ 1874. ‘Lectures delivered in America,’ 1875. ‘All Saints' Day, and other Sermons’ (edited by W. Harrison), 1878. Kingsley also published some single sermons and pamphlets besides those mentioned in the text. Various selections have also been published. He wrote prefaces to Miss Winkworth's translation of ‘Tauler’ and the ‘Theologia Germanica,’ and to Brooke's ‘Fool of Quality.’ Kingsley coined the term pteridomania in his 1855 book Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore.[8]

Critical introduction[]

Charles Kingsley, author on the one hand of Cheap Clothes and Nasty, and of The Water-Babies on the other, was the type of a certain order of modern man: the man of whom much is expected, who is trained up to the fulfilment of many purposes, who is subject to many influences, open to many sorts of impressions, and possessed of many active holds upon life. He came of choice and generous stock; and from the first it was determined for him that he should do something and be somebody. It seems natural that he should have developed into one of the busiest men of his time. His, indeed, was a sane and active mind in a sane and active body, and he made noble use of the endowment. He died after a lifetime of such steady, earnest, and varied endeavour as is within the compass of but few.

As a writer, he is seen to greatest advantage in his prose, which is clear, nervous, full of vivacity and significance, and often very powerful and expressive. His verse, however, has a great deal of merit, and may be read with some true pleasure. He had a capacity for poetry, as he had capacities for many things beside, and he cultivated it as he cultivated all the others. His sense of rhythm seems to have been imperfect. His ear was correct, and he often hit on a right and beautiful cadence; but his music grows monotonous, his rhythmical ideas are seldom well sustained or happily developed.

His work abounds in charming phrases and in those verbal inspirations that catch the ear and linger long about the memory:— as witness the notes that are audible in the opening verses of "The Sands of Dee," the "pleasant Isle of Avès" of "The Last Buccanier," and the whole first stanza of the song of the Old Schoolmistress in The Water-Babies. But, as it is with his music, so is it with his craftsmanship as well. He would begin brilliantly and suggestively and end feebly and ill, so that of perfect work he has left little or none.

It is also to be noted of him that his originality was decidedly eclectic — an originality informed with many memories and showing sign of many influences; and that his work, even when its purpose is most dramatic, is always very personal, and has always a strong dash in it of the sentimental manliness, the combination of muscularity and morality, peculiar to its author. For the rest, Kingsley had imagination, feeling, some insight, a great affection for man and nature, a true interest in things as they were and are and ought to be — above all, as they ought to be!— and a genuine vein of lyric song.

His work is singularly varied in quality and tone as in purpose and style. Now it is hot and crude and violent — violent without power — as in "Alton Locke’s Song" and "The Bad Squire"; now, mannered and affected, as in "The Red King" and "The Weird Lady"; now, human and pathetic, as in "The Last Buccanier" and "Airly Beacon"; now, fierce and random and turbid, as in "Santa Maura" and "The Saint’s Tragedy"; now, aesthetic, experimental, even imitative, as in "The Longbeards’ Saga", "Earl Haldane’s Daughter", and "Andromeda"; now rhetorical and vague and insincere, and now natural, simple, direct, large in handling and earnest in expression, as only true poetry can be.

There are fine passages everywhere in Kingsley, and of spirit and point he has an abundance. But it is as a writer of songs that the public have chosen to remember him, and they, as it seems to me, are right. The best of his songs will take rank with the 2nd best in the language.

On the whole, Charles Kingsley was not so much a man of genius as a man of many instincts, many accomplishments, and many capacities. He will always be remembered with respect and admiration; for he was, in John Mill’s phrase, ‘one of the good influences of his time,’ and an excellent writer beside.[9]

Recognition[]

Charles Kingsley statue at Bideford, Devon, England. Photo by Mark New. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

A cross was erected by his wife in Eversley churchyard. A Kingsley Memorial Fund provided a restoration of the church and a bust (by Mr. Woolner) in Westminster Abbey.[7]

Kingsley's life was written by his widow in 1877, entitled Charles Kingsley: His letters and memories of his life. A portrait is prefixed to the 1st volume, and an engraving from Mr. Woolner's bust to the 2nd.[7]

On 23 September 1876, the memorial bust of Kinsgley was unveiled in St George's chapel, Westminster Abbey. In 2014 it was moved to Poets' Corner.[10]

Kingsley's novel Westward Ho! led to the founding of a town by the same name — the only place name in England which contains an exclamation mark — and even inspired the construction of a railway, the Bideford, Westward Ho! and Appledore Railway. Few authors can have had such a significant effect upon the area which they eulogised. A hotel in Westward Ho! was named for him and it was also opened by him.

A hotel opened in 1897 in Bloomsbury, London, was named after Kingsley. It still exists, and is now known as The Kingsley by Thistle. The original reason for the chosen name was that the hotel was opened by teetotallers who admired Kingsley for his political views and his ideas on social reform.

His poems "Airly Beacon" and "The Sands of Dee" were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[11]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Poems. New York; John W. Lovell, 1848; 2nd edition, Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1856.

- Andromeda, and other poems. London: John W. Parker, 1858; Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1858.

- Poems. London & New York: Macmillan, 1889.

- The Poems of Charles Kingsley. London & Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; London & Toronto: J.M. Dent / New York: E.P. Dutton, 1913.

Plays[]

- The Saint's Tragedy. London: John W. Parker, 1848.

Novels[]

- Alton Locke, Tailor and Poet: An autobiography. London: Chapman & Hall, 1850; New York: A.L. Burt, 1850. Volume I, Volume II

- Yeast: A problem. London: Nelson, 1851; New York: Harper, 1851.

- Hypatia; or, New foes with an old face. London: John W. Parker, 1853. Volume I, Volume II

- Westward Ho!.London: Nelson, 1855; New York: A.L. Burt, 1855; Chicago: Hooper, Clarke, 1855.

- Two Years Ago (a novel). (2 volumes), Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1857; Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1857. Volume I, Volume II.

- Hereward the Wake: "last of the English", a novel. London & Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1866.

- The Tutor's Story: An unpublished novel. London: Smith, Elder, 1916; New York: Dodd, Mead, 1916; Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1916.

Non-fiction[]

- Twenty-five Village Sermons. London: John W. Parker, 1849; Philadelphia: H. Hooker, 1854.

- Cheap Clothes and Nasty. London: William Pickering, 1850.

- Phaeton, or Loose Thoughts for Loose Thinkers. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1852; Philadelphia: Herman Hooker, 1854.

- Sermons on National Subjects. London: Richard Griffin, 1854.

- Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1855.

- Alexandria and her Schools: Four lectures delivered at the Philosophical Institution. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1854.

- Sermons for the Times. London: J.W. Parker, 1855.

- The Good News of God: Sermons. London: J.W. Parker, 1859; New York: Burt, Hutchinson, & Abbey, 1859.

- Sir Walter Raleigh and His Time, with other papers. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1859.

- Miscellanies. (2 volumes), London: John W. Parker, 1859. Volume I, Volume II.

- The Limits of Exact Science applied to History: An inaugural lecture, delivered before the University of Cambridge. Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1860.

- New Miscellanies. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860.

- Town and Country Sermons. London: Parker, Son & Bourn, 1861.

- The Gospel of the Pentateuch: A set of parish sermons. London: Parker, Son, & Bourn, 1863.

- The Roman and the Teuton: A series of lectures delivered before the University of Cambridge. Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1864.

- David, and other sermons. Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1865.

- Three Lectures delivered at the Royal Institution, on The Ancient Régime.London: Macmillan, 1867.

- The Water of Life, and other sermons. London: Macmillan, 1867; Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1868.

- Discipline, and other sermons. London: Macmillan, 1868.

- The Hermits'. London: Macmillan, 1868; Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1868.

- Women and Politics. London: London National Society for Women's Suffrage, 1869.

- At Last: a Christmas in the West Indies. London & New York: Macmillan, 1871; New York: Harper, 1871.

- Sermons on National Subjects: Second series. London: Macmillan, 1872.

- Town Geology. London: Strahan, 1872; New York: D. Appleton, 1873.

- Discipline, and other sermons (1872)

- Prose Idylls, new and old. London: Macmillan, 1873.

- Plays and Puritans, and other historical essays. London: Macmillan, 1873,

- Health and Education. London: W. Isbister, 1874; New York: D. Appleton, 1874.

- Westminster Sermons. London & New York: Macmillan, 1874.

- Lectures delivered in America in 1874. London: Longmans, Green, 1875; Philadelphia: Coates, 1875.

- Village Sermons, and Town and country sermons. London: Macmillan, 1877; London & New York: Macmillan, 1879.

- All Saints Day, and other sermons. London: C. Kegan Paul, 1878.

- True Words for Brave Men. London: C. Kegan Paul, 1878.

- Scientific Lectures and Essays. London: Macmillan, 1880.

- Historical Lectures and Essays. London & New York: Macmillan, 1880.

- Sanitary and Social Lectures and Essays. London: Macmillan, 1880.

- Literary and General Lectures and Essays. London: Macmillan, 1880.

- Out of the Deep: Words for the sorrowful. London & New York: Macmillan, 1880.

- Charles Kingsley's Sermons. New York: Worthington, 1890.

- The Eternal Goodness, and other sermons. Boston & New York: T.Y. Crowell, 1895.

- Words of Advice to School-Boys; Collected from hitherto unpublished notes and letters of the late Charles Kingsley;(edited by E.F. Johns). London: Simpkin, 1912.

- Charles Kingsley's American Notes: Letters from a lecture tour, 1874 (edited by Robert Bernard Martin). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1958.

Juvenile[]

- The Heroes; or, Greek fairy tales for my children. London: Blackie, 1855.

- The Water-Babies: A fairy tale for a land baby. London: Ward, Lock, 1863; London & New York: Nelson, 1863; London: J.M. Dent, 1957.

- Madam How and Lady Why; or, First lessons in earth lore for children. London: Bell & Daldy, 1870.

Collected editions[]

- Works. London: Macmillan, 1878.

- Masterpieces from Charles Kingsley. Philadelphia: Rodgers, 1890.

- Selections from Some of the Writings of Charles Kingsley. London: Macmillan, 1884.

- Daily Thoughts: Selected from the writings of Charles Kingsley by his wife (selected by Frances Eliza Grenfell Kingsley). London & New York: Macmillan, 1884.

- Novels and Poems. New York: J.F. Taylor, 1898.

- Novels, Poems, and Letters. New York & London: Co-operative Publication Society, 1898-1899. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III, Volume IV, Volume V, Volume VI, Volume VII, Volume VIII, Volume IX, Volume X

- The Pocket Charles Kingsley. London: Chatto & Windus, 1907.

Letters[]

- Frances Eliza Grenfell Kingsley, Charles Kingsley: His letters and memoirs of his life. London: C. Kegan Paul, 1872; London: H.S. King, 1872; London & New York: Macmillan, 1921. Volume I, Volume II.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[12]

Young And Old a poem by Charles Kingsley

See also[]

The Dead Church a poem written by Charles Kingsley

References[]

- Darwin, Charles (1887), Darwin, F, ed., The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter., London: John Murray (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin) Retrieved on 20 July 2007

Stephen, Leslie (1892) "Kingsley, Charles" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 31 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 175-181. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 4, 2018.

- Frederick Waddy, ""Canon Kingsley," Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1873), 90-92. Wikisource, Wikimedia, Web, Jan. 6, 2011.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Kingsley, Charles," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 222. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 4, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Stephen, 175.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Stephen, 176.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 Stephen, 177.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Stephen, 180.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Stephen, 178.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 Stephen, 179.

- ↑ Peter D. A. Boyd's Pteridomania

- ↑ from William Ernest Henley, "Critical Introduction: Charles Kingsley (1819-1875)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Feb. 16, 2017.

- ↑ Charles Kingsley, People, History, Westminster Abbey. Web, July 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Alphabetical list of authors: Jago, Richard to Milton, John". Arthur Quiller-Couch, editor, Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919). Bartleby.com, Web, May 6, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Charles Kingsley, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Sep. 13, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Drifting Away: A Fragment"

- Charles Kingsley in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900: ""Airly Beacon", "The Sands of Dee"

- Kingsley, Charles (1819-1875) (5 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- Kingsley in The English Poets: An anthology: Pallas in Olympus (from Andromeda, "The Last Buccaneer, The Sands of Dee (from Alton Loch)," "A Farewell," "Dolcino to Margaret," "Airly Beacon," A Boat-Song (from Hypatia), The Song of Madame Do-as-you-would-be-done-by (from The Water Babies), "The 'Old, Old Song'"

- Kingsley in A Victorian Anthology: from The Saint's Tragedy, "The Sands of Dee," "The Three Fishers," "A Myth," "The Dead Church," "Anromeda and the Sea-Nymphs," "The Last Buccaneer," "Lorraine," "A Farewell"

- Index entry for Charles Kingsley at Poets' Corner

- Charles Kingsley at PoemHunter (86 poems)

- Charles Kingsley at Poetry Nook (131 poems)

- Audio / video

- Charles Kingsley poems at YouTube

- Books

- Works by Charles Kingsley at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- Works by Charles Kingsley at Internet Archive

- Charles Kingsley at the Online Books Page

- Charles Kingsley at Amazon.com

- Charles Kingsley at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- About

- Charles Kingsley in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Kingsley, Charles in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Frederick Waddy, ""Canon Kingsley," Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1873)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Kingsley, Charles

|