Pauline Johnson (1861-1913) circa 1895, in Canadian Singers and their Songs, 1919. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Emily Pauline Johnson (March 10, 1861 - March 7, 1913), was a Canadian poet, popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as both a writer and a performance poet.

Life[]

Overview[]

Commonly known as E. Pauline Johnson or Pauline Johnson, also known in Mohawk as Tekahionwake,[1] she was noted for poetry that celebrated her First Nations heritage; her father was a Mohawk chief and her mother an English immigrant. One such poem, "The Song my Paddle Sings," is frequently anthologized. Her poetry was published in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain.

Johnson belonged to a generation of widely read writers who began to define a Canadian literature. While her literary reputation declined in the years after her death, since the late 20th century there has been renewed interest in her life and works.

Family histories[]

Chiefswood, the birthplace of Pauline Johnson, a National Historic Site of Canada. Photo by Steve Colwill. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Johnson was born at Chiefswood, the family home built by her father in 1856 on the Six Nations Indian Reserve outside Brantford, Ontario. She was the youngest of 4 children of Emily Susanna (Howells) Johnson (1824-1898), a native of England, and George Henry Martin Johnson (1816-1884), a Mohawk chief. Howells had immigrated to the United States in 1832 as a young child with her father, stepmother and siblings. Howells met Johnson while living with her older sister on the reserve, where her brother-in-law was a missionary.

The Mohawk ancestors of George Johnson had historically lived in what became the state of New York, their traditional homeland in the present-day United States. In 1758, Pauline Johnson's great-grandfather, Tekahionwake, was born in New York. When he was baptized, he took the name Jacob Johnson, taking his surname from Sir William Johnson, the influential British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who acted as his godfather.[2] The Johnson surname was subsequently passed down in the family.

After the American Revolutionary War began, Loyalists in the Mohawk Valley came under intense pressure. The Mohawk and three other Iroquois tribes were allies of the British rather than the rebel colonists. Jacob Johnson and his family moved to Canada. After the war they settled permanently in Ontario on land given by the Crown in partial compensation for Iroquois losses of territory in New York.

Jacob Johnson's son, John Smoke Johnson, had a talent for oratory, spoke English as well as Mohawk, and demonstrated his patriotism to the Crown during the War of 1812. As a result, John Smoke Johnson was made a Pine Tree Chief at the request of the British government.[3] Although John Smoke Johnson's title could not be inherited. His wife Helen (Martin) was descended from the Wolf Clan and a founding family of the Six Nations. Through her lineage and influence (as the Mohawk were matrilineal), their son George Johnson was named chief.

George Johnson inherited his father's gift for languages and began his career as a church translator on the Six Nations reserve. Assisting the Anglican missionary, Johnson met and fell in love with Emily Howells.

Emily Howells was born in England to a well-established British family who immigrated to the United States in 1832.[4] Her father Henry Howells was a Quaker, who intended to join the American abolitionist movement. Emily's mother, Mary Best Howells, had died when the girl was 5, before the family left England her father remarried before they immigrated. In the U.S., he moved his family to several American cities, where he founded schools to gain an income, before settling in Eaglewood, New Jersey.[5] After his 2nd wife died Howells married a third time, and fathered in total 24 children.[6] Although he opposed slavery and encouraged his children to "pray for the blacks and to pity the poor Indians. Nevertheless, his compassion did not preclude the view that his own race was superior to others".[7]

At age 21, Emily Howells moved to the Six Nations reserve in Ontario, Canada to join her older sister, who had moved there with her Anglican missionary husband. Emily helped her care for her growing family. After falling in love with George Johnson, Howells gained a better understanding of the Native peoples and some perspective on her father's beliefs.[7]

Howells and Johnson married in 1853. The interracial marriage displeased both the Johnson and Howells families. The birth of their first child reconciled the Johnson family to the marriage.[7]

In 1856 Johnson built Chiefswood, a wooden mansion where the family lived for years.

Youth and education[]

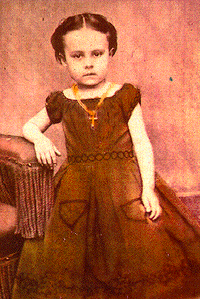

A young Pauline Johnson. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Emily and George Johnson encouraged their four children to respect and learn about both the Mohawk and the English aspects of their heritage. Because the children were born to a Native father, by British law they were legally considered Mohawk and wards of the British Crown. Because their mother was not Mohawk, they were excluded from aspects of the tribe's matrilineal culture. Their paternal grandfather John Smoke Johnson, who had also been a chief, was an authority in the lives of his grandchildren. He told them many stories in the Mohawk language, which they comprehended but did not speak fluently.[8] Pauline Johnson said that she inherited her talent for elocution from her grandfather. Late in life, she expressed regret for not learning more of his Mohawk heritage.[9]

Despite Emily and George Johnson's initial worries that their mixed-race family would not be socially accepted, they were acknowledged as a leading Canadian family [10] The Johnsons enjoyed a high standard of living, and their family and home were well known. Chiefswood was visited by intellectual and political guests such as inventor Alexander Graham Bell, painter Homer Watson, anthropologist Horatio Hale, and Lady and Lord Dufferin, Governor General of Canada.

A sickly child, Johnson did not attend Brantford's Mohawk Institute, established in 1834 as one of Canada's first residential schools for native children. Her education was mostly at home and informal, deriving from her mother, a series of non-Native governesses, a few years at the small school on the reserve, and self-directed reading in the family's expansive library. She became familiar with literary works by Byron, Tennyson, Keats, Browning, and Milton.[11] She enjoyed reading tales about Native peoples, such as Longfellow's epic poem The Song of Hiawatha and John Richardson's Wacousta.[12] At age 14, Johnson went to Brantford Central Collegiate with her brother Allen, and she graduated in 1877. A schoolmate was Sara Jeannette Duncan, who developed her own journalistic and literary career.

As government interpreter and hereditary Chief, George Johnson developed a reputation as a talented mediator between Aboriginal and European interests.[7] He was well respected in Ontario. However, he also made enemies because of his efforts to stop illegal trading of reserve timber. Physically attacked by Native and non-Native men involved in this traffic, Johnson suffered from health problems afterward. He died of a fever in 1884.[13]

Shortly after George Johnson's death in 1884, the family rented out Chiefswood. Pauline Johnson moved with her mother and sister to a modest home in Brantford.

Pauline Johnson posing. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Career[]

During the 1880s, Pauline Johnson wrote and performed in amateur theatre productions. She enjoyed the Canadian outdoors, where she traveled by canoe. In 1883 she published her earliest full-length poem, "My Little Jean," in the New York Gems of Poetry. She began to increase the pace of her writing and publishing afterward. In 1885 Charles G.D. Roberts published Johnson's "Cry from an Indian Wife" in The Week, Goldwin Smith's Toronto magazine. She based it on the battle of Cut Knife Creek during the Riel Rebellion. Roberts and Johnson became lifelong friends.[14]

In 1885, Johnson traveled to Buffalo, New York, to attend a ceremony honoring Iroquois leader Sagoyewatha (Red Jacket). She wrote a poem expressing admiration for him and a plea for reconciliation between British and Native peoples.[15] In 1886 she was commissioned to write an ode to mark the unveiling in Brantford of a statue honoring Joseph Brant, the important Mohawk leader during and after the American Revolutionary War. Her "Ode to Brant" was read at an October 13 ceremony before "the largest crowd the little city had ever seen."[16] It called for brotherhood between Native and white Canadians under British imperial authority.[17] The poem sparked a long article in the Toronto Globe and increased interest in Johnson's poetry and heritage. The Brantford businessman William F. Cockshutt read the poem,[16] as Johnson was reportedly too shy.[14]

During the 1880s, Johnson built her reputation as a Canadian writer, regularly publishing in periodicals such as Globe, The Week, and Saturday Night. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, she published nearly every month, mostly in Saturday Night.[16] Johnson was one of a group of Canadian authors contributing to a distinct national literature,.[18][19] The inclusion of 2 of her poems in W.D. Lighthall's anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion (1889), signaled her recognition.[20] British critic Theodore Watts-Dunton noted her for praise in his review of the anthology: he quoted her entire poem "In the Shadows" and called her "the most interesting poetess now living."[16]

The Young Men's Liberal Association invited Johnson to a Canadian Authors Evening, held January 16, 1892 at the Toronto Art School Gallery. The only woman at the event, she read to an overflow crowd, along with luminaries such as Lighthall, William Wilfred Campbell, and Duncan Campbell Scott. "The poise and grace of this beautiful young woman standing before them captivated the audience even before she began to recite - not read, as the others had done" - her dramatic monologue, "A Cry from an Indian Wife." Johnson was the only author to be called back for an encore. "She had scored a personal triumph and saved the evening from turning into a disaster."[16]

The success of this performance began the poet's 15-year stage career, as she was signed up by Frank Yeigh, who had organized the Liberal event. He gave her the headline for her first show on February 19, 1892, where she debuted a new poem written for the event, "The Song my Paddle Sings ."[16] Johnson was perceived as quite young (although she was then 31), a beauty, and an exotic Native performer.[21] After her first recital season, she decided to emphasize the Native aspects by assembling and wearing a feminine Native costume.[22] She wore it during the first part of the show, when reciting her dramatic "Indian" lyrics. At intermission she changed into fashionable English dress; in the second half, she appeared as a Victorian lady to recite her "English" verse.[16]

Johnson's decision to develop her stage persona, and the popularity it inspired, showed that the audiences she encountered in Canada, England, and the United States recognized and were entertained by Native peoples in performance. The 1890s were also the period of popularity of Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show and ethnological aboriginal exhibits.[23] She and her siblings inherited an artifact collection from their father, which included significant items such as wampum belts and spiritual masks. She used some items in her stage performances, but sold most later to museums, such as the Ontario Provincial Museum, or to collectors, such as the prominent American George Gustav Heye.[24]

Later life[]

Siwash Rock in Stanley Park, Vancouver, the story of which is told in Legends of Vancouver. Johnson's burial site is nearby. Photo by Another Believer. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

After retiring from the stage in August 1909, Johnson moved to Vancouver, British Columbia and continued writing. Her pieces included a series of articles for the Daily Province, based on stories related by her friend Chief Joe Capilano of the Squamish people of North Vancouver. In 1911, to help support Johnson, who was ill and poor, a group of friends organized the publication of these stories under the title Legends of Vancouver. They remain classics of that city's literature.

One of the stories was a Squamish legend of shape shifting: how a man was transformed into Siwash Rock "as an indestructible monument to Clean Fatherhood."[25] In another, Johnson told the history of Deadman's Island, a small islet off Stanley Park. In a poem in the collection, she named one of her favourite areas "Lost Lagoon", as the inlet seemed to disappear at low tide. The body of water has since been transformed into a permanent, fresh-water lake at Stanley Park, but it is still called "Lost Lagoon".

The posthumous Shagganappi (1913) and The Moccasin Maker (1913) are collections of selected stories first published in periodicals. Johnson wrote on a variety of sentimental, didactic, and biographical topics. Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson provided a provisional chronological list of Johnson's writings in their book Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (2000).

Johnson died of breast cancer in Vancouver on 7 March 7, 1913. Her funeral (the largest until then in Vancouver history) was held on what would have been her 52nd birthday. Her ashes were buried near Siwash Rock in Stanley Park. In 1922 a cairn was erected at the burial site, with an inscription reading in part, "in memory of one who's life and writings were an uplift and a blessing to our nation".[14]

Writing[]

Pauline Johnson monument in Stanley Park, Vancouver. Photo by Bobanney. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In her early works, Johnson wrote mostly about Canadian life, landscapes, and love in a post-Romantic mode, reflective of literary interests shared with her mother rather than her Mohawk heritage.[20]

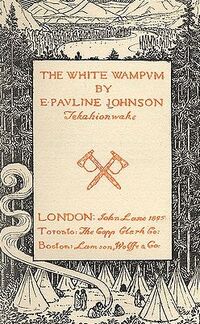

Scholars have had difficulty identifying Johnson's complete works, as much was published in periodicals. Her debut collection of poetry, The White Wampum, was published in London, England in 1895. It was followed by Canadian Born in 1903 and When George was King, and other poems, in 1908.

The contents of these volumes, together with additional poems, were published as Johnson's Collected Poems, Flint and Feather, in 1912, with an introduction by Watts-Dunton. Reprinted many times, this book was a best-selling title of Canadian poetry. [26]

Critical reputation[]

Despite the acclaim she received from contemporaries, Johnson's reputation declined sharply in the decades after her death.[27] It was not until 1961, with commemoration of the centenary of her birth, that she began to be recognized as an important Canadian cultural figure. A number of biographers and literary critics have downplayed her literary contributions, as they contend that her performances contributed most to her literary reputation during her lifetime.[28] W.J. Keith wrote: "Pauline Johnson's life was more interesting than her writing.... With ambitions as a poet, she produced little or nothing of value in the eyes of critics who emphasize style rather than content."[29]

Author Margaret Atwood admitted that she did not study literature by Native authors when preparing Survival: A thematic guide to Canadian literature (1972). At its publication, she had said she could not find Native works. She mused, "Why did I overlook Pauline Johnson? Perhaps because, being half-white, she somehow didn't rate as the real thing, even among Natives; although she is undergoing reclamation today."[30] Atwood's comments indicated that Johnson's multicultural identity contributed to her neglect by critics.

As Atwood noted, since the late 20th century, Johnson's writings and performance career have been reevaluated by literary, feminist, and postcolonial critics. They have appreciated her importance as a New Woman and a figure of resistance to dominant ideas about race, gender, Native Rights, and Canada.[31] The growth in literature written by First Nations people during the 1980's and 1990's has prompted writers and scholars to investigate Native oral and written literary history, to which Johnson made a significant contribution.[32]

Recognition[]

Ceremony unveiling the Pauline Johnson monument at her burial site in Stanley Park, 1922.

- In 1922, the city of Vancouver erected a monument in Pauline Johnson's honor in her well-loved Stanley Park.

- In 1945, Johnson was designated a Person of National Historic Significance.[33]

- In 1961, on the centennial of her birth, Johnson was celebrated with a commemorative stamp bearing her image, "rendering her the first woman (other than the Queen), the first author, and the first aboriginal Canadian to be thus honored.".[34]

- 4 Canadian schools have been named in Johnson's honor: elementary schools in West Vancouver, British Columbia; Scarborough, Ontario; Hamilton, Ontario; and Burlington, Ontario; and a secondary school, Pauline Johnson Collegiate & Vocational School, in Brantford, Ontario.

- Chiefswood, Johnson's childhood home constructed in 1856 in Brantford, has been listed as a National Historic Site of Canada, because of both her father's and her historical importance. Preserved as a house museum, it is the oldest Native mansion surviving from pre-Confederation times.[33]

- An Ontario Historical Plaque was erected in front of the Chiefswood house museum by the province to commemorate E. Pauline Johnson's role in the region's heritage.[35]

- On 11 March 2008, City Opera Vancouver announced its commission of Pauline, a chamber opera to star the dramatic mezzo Judith Forst. The composer was Christos Hatzis, with libretto by Margaret Atwood. The work was planned for premiere in early 2011. The first opera to be written about Pauline Johnson, it is set in Vancouver in March 1913, in the last week of her life.

- The Canadian actor Donald Sutherland narrated the following quote from her poem "Autumn's Orchestra", at the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

- Know by the thread of music woven through

- This fragile web of cadences I spin,

- That I have only caught these songs since you

- Voiced them upon your haunting violin.

- In 2010, composer Jeff Enns was commissioned to create a song based on Johnson's poem "At Sunset". His work was sung and recorded by the Canadian Chamber Choir under the artistic direction of Julia Davids.[36][37]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The White Wampum. Toronto: Copp Clark / London: John Lane / Boston: Lamson, Wolffe, 1895.

- In the Shadows. Gouverneur, NY: Adirondack, 1898.

- Canadian Born. Toronto: G.N. Morang, 1903.

- When George Was King, and other poems. Brockville, ON: Brockville Times, 1908.

- Flint and Feather. Toronto: Musson, 1912.

- Flint and Feather: Complete poems of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (edited by Theodore Watts-Dunton). Toronto: Musson, 1913; 18th edition, 1969.

- Pauline Johnson, Her Life and Work: Biography written by and poems selected by Marcus Van Steen (edited by Van Steen). Toronto: Hodder & Stoughton, 1965.

Fiction[]

- The Mocassin Maker. Toronto: William Briggs, 1913.

- (edited by A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1987; Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press,1988.

Juvenile[]

- Legends of Vancouver. Vancouver: privately printed, 1911; Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild, & Stewart, 1911; Vancouver: Vancouver Business and Professional Women's Club, 1952

- (illustrated by Laura Wee Lay Laq). Kingston, ON: Quarry Press, 1981

- Honolulu, HI: University Press of the Pacific, 2003.

- The Shagganappi. Toronto: William Briggs, 1913.

- The Lost Island. Vancouver, BC: Simply Read, 2004.

Collected editions[]

- E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake): Collected poems and selected prose (edited by Carole Gerson & Veronica Strong-Boag). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[38]

Poems by Johnson[]

Canadian Born (Emily Pauline Johnson Poem)

Thistle down by E Pauline Johnson

See also[]

Day Dawn (Emily Pauline Johnson Poem)

- The Confederation poets

- Canadian First Nations Poets

- List of Canadian poets

- Timeline of Canadian poetry

References[]

The Song My Paddle Sings - video 640x480 MP4

- Crate, Joan. Pale as Real Ladies: Poems for Pauline Johnson, London, ON: Brick Books, 1991. ISBN 0-919626-43-2

- Gerson, Carole (1998), ""The Most Canadian of all Canadian Poets": Pauline Johnson and the Construction of a National Literature", Canadian Literature 158: 90-107

- Gray, Charlotte (2002), Flint and Feather: The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake, Toronto: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-002000-65-2

- Jackel, David (1983), "Johnson, Pauline", The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-195402-83-9

- Johnston, Shelia M.F. (1997), Buckskin & Broadcloth: A Celebration of E. Pauline Johnson-Tekahionwake 1861-1913, Toronto: Natural Heritage, ISBN 1-896219-20-9

- Keith, W. J. (2002), "2040", Canadian Book Review Annual, Toronto: Peter Martin Associates

- Keller, Betty. Pauline: A Biography of Pauline Johnson. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1981. ISBN 0-888943-22-9

- Lyon, George W. "Pauline Johnson: A Reconsideration", Studies in Canadian Literature 15 (1990): 136-159.

- McRaye, Walter. Pauline Johnson and Her Friends. Toronto: Ryerson, 1947.

- Monture, Rick (2002), "'Beneath the British Flag': Iroquois and Canadian Nationalism in the Work of Pauline Johnson and Duncan Campbell Scott", Essays on Canadian Writing: 118-141

- Shrive, Norman. "What Happened to Pauline?", Canadian Literature 13 (1962): 25-38.

- Strong-Boag, Veronica; Gerson, Carole (2000), Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-802041-62-0

- Van Steen, Marcus (1965), Pauline Johnson: Her Life and Work, Toronto: Hodder & Stoughton

Fonds[]

Notes[]

- ↑ pronounced: dageh-eeon-wageh, literally: 'double-life']. Pauline Johnson Archive: Tekahionwake, "Tekahionwake: An Indian poetess in London", Archives & Research Collections, McMaster University. Web, Nov. 15, 2009.

- ↑ Douglas Leighton, John "Smoke" Johnson, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- ↑ Johnston 1997, 21.

- ↑ Gray, 8-9}}

- ↑ Gray, 11.

- ↑ Gray, 12.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Gray, 57.

- ↑ Gray, 47.

- ↑ Johnston, 21.

- ↑ Gray, 61.

- ↑ Jackel 1983, 398.

- ↑ Gray, 53.

- ↑ Gray, 81.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Pauline Johnson Biography," Famous Biographies, QuotesQuotations.com, Web, Apr. 30, 2011.

- ↑ Gray, 90

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 John Coldwell Adams, "Pauline Johnson"," Confederation Voices, Canadian Poetry, 30 April 2011.

- ↑ Gray, 90.

- ↑ Monture 2002.

- ↑ Gerson 1998.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Strong-Boag & Gerson, 101.

- ↑ Strong-Boag & Gerson, 102.

- ↑ Strong-Boag & Gerson, 9-10.

- ↑ Strong-Boag & Gerson, 111.

- ↑ Michelle A Hamilton, Collections and Objections: Aboriginal material culture in xouthern Ontario, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010

- ↑ Legends of Vancouver.

- ↑ J.W. Garvin, "E. Pauline Johnson," Canadian Poets (Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1916), 147, UPenn.edu, Web, June 23, 2011.

- ↑ Gerson 1998, 91.

- ↑ See, for example, Van Steen 1965, or Jackel 1983.

- ↑ Keith 2002.

- ↑ Atwood, 243.

- ↑ Strong-Boag & Gerson, 3.

- ↑ Strong-Boag & Gerson, 174.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Chiefswood National Historic Site Website

- ↑ Gerson 1998, 90.

- ↑ Ontario Plaque

- ↑ Video for At Sunset performed by Canadian Chamber Choir

- ↑ In Good Company, Canadian Chamber Choir CD including "At Sunset"

- ↑ Search results = au:E. Pauline Johnson, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Sep. 8, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- Emily Pauline Johnson at the Poetry Foundation

- Johnson in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "The Song My Paddle Sings," "At Husking Time," "The Vagabonds"

- 5 poems by Johnson: "The Songster," "In the Shadows," "Marshlands," "Autumn's Orchestra," "The Idlers"

- Johnson, E. Pauline (1861-1913) (5 poems - Brier: Good Friday, Flint and Feather, The Pilot of the Plains, Shadow River: Muskoka, The Song my Paddle Sings) at Representative Poetry Online

- E. Pauline Johnson in Canadian Poets (7 poems)

- Emily Pauline Johnson at PoemHunter (97 poems)

- Puuline Johnson at Poetry Nook (198 poems)

- Audio

- Books

- Works by Pauline Johnson at Project Gutenberg

- Pauline Johnson at Amazon.com

- About

- Pauline Johnson in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Pauline Johnson in the Canadian Encyclopedia

- Pauline Johnson at Canadian Women Poets

- Pauline Johnson at NNDB

- Johnson, Emily Pauline in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- E. Pauline Johnson at English-Canadian Writers

- Etc.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

| This page uses content from Wikinfo . The original article was at Wikinfo:Pauline Johnson. The list of authors can be seen in the (view authors). page history. The text of this Wikinfo article is available under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license. |

|