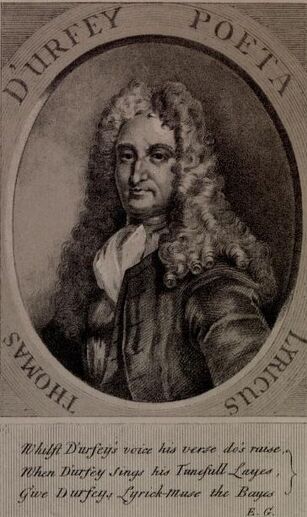

Thomas D'Urfey (1653-1723), from Songs Compleat, Pleasant and Divertive. London: W. Pearson for Jacob Tonson, 1719. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Thomas D'Urfey (1653 - 26 February 1723) was an English poet, playwright, and wit. He was an important innovator and contributor in the evolution of the ballad opera.

Life[]

Overview[]

D'Urfey was a well-known man-about-town, a companion of Charles II, who lived on to the reign of George I. His plays are now forgotten, and he is best known in connection with a collection of songs, Pills to Purge Melancholy. Addison describes him as a "diverting companion," and "a cheerful, honest, good-natured man." His writings are nevertheless extremely gross. His plays include Siege of Memphis (1676), Madame Fickle (1677), Virtuous Wife (1680), and The Campaigners (1698).[1]

Youth and family[]

D'Urfey, generally known as Tom Durfey, was born at Exeter in 1653. The date usually given, 1649, appears to be erroneous. He was of Huguenot descent, and maintained his protestantism to his last hour. His grandfather left La Rochelle before the siege ended in 1628, bringing his son with him, and settled in Exeter, where D'Urfey's father married Frances, a gentlewoman of Huntingdonshire, of the family of the Marmions, and thus connected with Shackerley Marmion the dramatist. Tom's uncle was Honoré D'Urfé, author of the romance of ‘Astrée,’ so much admired by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a relationship which is proudly referred to in D'Urfey's own writings.[2]

Career[]

He had been intended for the law, but says: "My good or ill stars ordained me to be a knight-errant in the fairy field of poetry." His 1st play was produced at the King's Theatre in 1676, and printed in 4to, a bombastic tragedy entitled The Siege of Memphis; or, The ambitious queen. He pleased the town more with his comedies of The Fond Husband; or, The plotting sisters, licensed 15 June 1676, and Madam Fickle; or, The witty false one, 1677. 2 more followed in 1678, The Fool turn'd Critic and Trick for Trick; or, The debauched hypocrite.[3]

His Squire Oldsapp; or, The night adventurers, 1679; The Virtuous Wife; or, Good luck at last, 1680; Sir Barnaby Whig; or, No wit like a woman's, 1681; and 2 others in 1682, The Royalist and The Injured Princess; or, The Fatal wager (which he called a trag-comedy), were full of bustle and intrigue, lively dialogue, and sparkling songs set to music by his friends Henry Purcell, Thomas Farmer, and Dr. John Blow. These songs increased his popularity.[3]

He was in demand to write birthday odes, epithalamia, prologues and epilogues, many of which are extant. He had joined Richard Shotterel on an heroic poem, Archerie Revived, and brought out his New Collection of Songs and Poems, 1683, among which was the memorable one beginning "The night her blackest sables wore,’ long afterwards erroneously claimed for Francis Semple of Beltrees.[3]

Amid all the commotion of the sham popish plot D'Urfey preserved the favor of both the court and the city. He was utterly devoid of malice, his satirical spirit was mirthful and never revengeful. Even when bitterly lampooned by the quarrelsome Tom Brown as "Thou cur, half French, half English breed" (who mocked him regarding a duel at Epsom in 1689 with one Bell, a musician, "I sing of a Duel, in Epsom befell, 'twixt Fa-sol-la D'Urfey and Sol-la-mi Bell), D'Urfey made no angry rejoinder, but took the abuse as a joke. He knew that the laugh was always on his side against the heavier hand. Both D'Urfey and Tom Brown were represented as subjected to a mock-trial in the Sessions of the Poets, holden at the foot of Parnassus Hill, before Apollo, July the 9th, 1696[3].

It was only by Jeremy Collier that he could be provoked to reply, and even then it was chiefly in a song, "New Reformation begins through the nation!" which he embedded in the preface to his Campaigners, a comedy of 1698. Collier had first assailed him in A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage, &c., 1698, chiefly on account of D'Urfey's play of Don Quixote. Of all the combatants the lightest-hearted and least harmed was Tom.[3]

Before this date he produced on the stage and in quarto, seriatim, ‘The Commonwealth of Women,’ 1686; ‘Banditti,’ 1686; ‘A Fool's Preferment,’ 1688; ‘Bussy d'Amboise,’ adapted from Chapman's tragedy, and ‘Love for Money; or, the Boarding School,’ both in 1691; ‘The Marriage Hater Matched,’ concerning which he wrote a letter to Mr. Gildon, 1692; and ‘The Richmond Heiress; or, A Woman Once in the Right,’ 1693. His Comical History of Don Quixote was in 3 parts, 2 of which appeared in 1694, the third in 1696. His Cynthia and Endymion, an opera, and The Intrigues of Versailles, a comedy, belonged to 1697.[3]

On Thursday, 12 May 1698, the justices of Middlesex took proceedings against Congreve and D'Urfey (Luttrell, iv. 379). In the preface to his Campaigners, 1698, he fairly encountered his assailant the nonjuror, and says that "the first time he saw Collier was under the gallows, where he pronounced the absolution to wretches justly condemned by law to die for the intended murder of the king [William III] and the subversion of the protestant religion." This refers to the execution of Sir John Friend and Sir William Parkyns, in April 1696.[3]

D'Urfey's Famous History of the Rise and Fall of Massaniello was a play in 2 parts, the 1st of which was printed the next year, 1699, the 2nd in 1700. His comedy of The Bath; or, The western lass, followed in 1701. In his burlesque, Wonders in the Sun; or, the Kingdom of the Birds,’ a comic opera with music composed by Giovanni Battista Draghi, he brought on the stage actors dressed as parrots, crows, etc., and the business was farcical in the extreme. This justified the remark of Dryden, that "You don't know my friend Tom so well as I do. I'll answer for it he will write worse yet!" But Dryden, after his own conversion to Romanism, could not feel pleased at D'Urfey's protestant zeal. Moreover, he had in 1693 written a prologue to The Volunteers; or, The stockjobbers,’ of Dryden's rival, Tom Shadwell; and again in 1694 to J. Lacy's Sir Hercules Buffoon.[3]

The republication of D'Urfey's own songs (with the music), both in single sheets and in volumes, 3 collections between 1683 and 1685, had been continually bringing money from John Playford and presents from private patrons. Most of these songs appeared in successive editions of Wit and Mirth; or, Pills to purge melancholy, the earliest volume of which (but without music) is dated 1684; the proper series, dated 1699 and 1700, was followed at short intervals in 1706, 1710, &c., by similar collections, some entitled Songs Compleat, by Tom D'Urfey,[3] until in 1719, with a supplementary 6th volume in 1720, the whole were reissued in what may be called a standard edition, whereof D'Urfey's own songs filled the first 2 volumes, with a few of his poems and prologues at the end. The title of An Antidote against Melancholy: Made up in pills had been 1st used in 1661.[4]

In 1704 was issued his Tales, Tragical and Comical (dedicated to the Duke of Argyll), 6 in number, and in verse, respectively adapted from Xenophon's Cyropædia, Straparola, Machiavelli's Belphegor, and Boccaccio. His Tales: Moral and comical followed in 1706, comprising "The Banquet of the Gods," "Titus and Gissippus," "The Prudent Husband," and "Loyalty's Glory."[4]

A new ode, "Mars and Plutus," in an entertainment made for the Duke of Marlborough in 1706, was but one of the innumerable loyal ditties with which he hailed the victories of the army; another being "The French Pride abated,’ of the same date.[4]

2 of his comedies in 1709 were intended "to ridicule the ridiculers of our established doctrine" and the pretenders of his day; one was The Modern Prophets,’ the other was titled The Old Mode and the New; or, The country miss and her furbelow.[4]

Social life[]

Although of convivial habits, he was never drunk. His love and reverence for his mother are shown in his "Hymn to Piety, to my dear Mother, Mrs. Frances D'Urfey, written at Cullacombe, September 1698," beginning "O sacred Piety, thou morning star, that shew'st our day of life serene and fair."[5]

4 successive monarchs had been amused by him and had shown him personal favour. Charles II had leaned familiarly on his shoulder, holding a corner of the same sheet of music from which D'Urfey was singing the burlesque song, "Remember, ye Whigs, what was formerly done." James II had continued the friendship previously shown when he was Duke of York, and had often found benefit from the song-writer's attachment to his person, despite differences in religious opinions. D'Urfey wrote "An Elegy upon Charles II and a Panegyric on James II" in 1685. William and Mary gave solid marks of favour, D'Urfey writing "Gloriana, a funeral Pindarique Ode," in Mary's memory, 1695. Queen Anne delighted in his wit, and gave him 50 guineas when she admitted him to sing to her at supper, because he lampooned the Princess Sophia (then next in succession to herself), by his ditty, "The Crown's too weighty for shoulders of 'Eighty!"[4]

The Earl of Dorset had welcomed him at Knole Park, and had his portrait painted there. He was often at the Saturday reception of poets at Leicester House. At Winchendon, Buckinghamshire, Philip, duke of Wharton, enjoyed his company and erected a banqueting-house in the garden, called Brimmer Hall, chiefly on his account. He sang his own songs, with vivacity, most effectively, although he stammered in ordinary speech. He said, "The Town may da-da-da-m me as a poet, but they sing my songs for all that."[4]

Writing to Henry Cromwell, 10 April 1710, Alexander Pope mentions having

- learned without book a song of Mr. D'Urfey's, who is your only poet of tolerable reputation in this country. He makes all the merriment in our entertainments. Any man of any quality is heartily welcome to the best toping-table of our gentry who can roundly hum out some fragments or rhapsodies of his works.... Dares any one despise him who has made so many men drink?... But give me your ancient poet, Mr. D'Urfey’ (Pope, Correspondence, v. infra).[4] Pope refers to D'Urfey in the Dunciad, bk. iii. lines 145–148, when addressing Ned Ward, "Another D'Urfey, Ward, shall sing in thee!" He also wrote "a drolling prologue’ for what was said to be D'Urfey's last play."'Mr. Dryden's boy’ had been talked about, but Tom D'Urfey ‘was the last English poet who appeared in the streets attended by a page’ (Notes to the Dunciad).[4]

When Rowe died, in 1718, Arbuthnot wrote to Swift: ‘I would fain have Pope get a patent for the [laureate's] place, with a power of putting D'Urfey in as deputy." Gay mentions that D'Ureym ran his muse with what was long a favourite racing song, "To horse, brave boys, to Newmarket, to horse!" (first printed in 1684 in D'Urfey's Choice New Songs). Addison or Steele praises the same song, but D'Urfey wrote another Newmarket song, "The Golden Age is come!" which was sung before Charles II.[4]

Last years[]

Hitherto he had not fared ill, with the profits of benefit nights, but his dramatic works no longer attracted the public, and he seems to have fallen into poverty, although he had never married or indulged in prodigal expenditure.[4]

D'Urfey fell into distress, soon after he had produced his song on "The Moderate Man," although "living in a blooming old age, that still promises many musical productions; for if I am not mistaken," says Joseph Addison, "our British swan will sing to the last." A friendly notice on Thursday, 28 May 1713, in No. 67 of the Guardian, brought before the public the condition of their "good old friend and contemporary."[4]

Addison and Sir Richard Steele, whose affection for D'Urfey was the stronger, induced the managers of Drury Lane to devote 15 June 1713 to a performance of D'Urfey's Fond Husband; or, The plotting sisters, a comedy which Charles II had witnessed 3 times in the first 5 nights. Steele had in No. 82 of the Guardian written to remind his readers "that on this day, being the 15th of June,[4] The Plotting Sisters is to be acted for the benefit of the author, my old friend Mr. D'Urfey."[5]

Another benefit for D'Urfey was given at Drury Lane on 3 June 1714, when he appeared and spoke an "Oration on the Royal Family and the prosperous state of the Nation," being his 2nd appearance, before the performance of Court Gallantry; or, Marriage a-la-Mode.[5]

In 1721 William Chetwood, at the Cato's Head, Covent Garden, published a volume entitled New Operas and Comical Stories and Poems on Seueral Occasions, neuer before printed: Being the remaining pieces written by Mr. D'Urfey. Among these were The Two Queens of Brentford; or, Bayes no poetaster, a comic opera, a sequel to The Rehearsal); The Grecian Heroine; The Athenian Jilt; Ariadne; and a few miscellanies.[5]

D'Urfey died, "at the age of seventy," on 26 February 1723, and was buried at St. James's Church, Piccadilly. He was buried handsomely at the expense of the earl of Dorset (Le Neve, MS. Diary; Genest writes "on March 11"). Steele followed him to the grave, and wore the watch and chain which D'Urfey bequeathed to him. Printed 3 years later in Miscellaneous Poems, i. 6, 1726, is an "Epitaph upon Tom D'Urfey:"—

Here lyes the Lyrick, who, with tale and song,

Did life to three score years and ten prolong;

His tale was pleasant and his song was sweet,

His heart was cheerful — but his thirst was great.

Grieve, Reader, grieve, that he, too soon grown old,

His song has ended, and his tale is told.[5]

Writing[]

His comedies were not more licentious than Dryden's or Ravenscroft's, or others of their day, but few kept possession of the stage, although The Plotting Sisters was revived in 1726, 1732, and 1740. 3 editions of it appeared in his lifetime, but no modern reprint of his dramas has been attempted, the contemporary issue having been large enough to keep the market supplied.[5]

His songs have never lost popularity, and many are still sung throughout Scotland under the belief that they were native to the soil. D'Urfey certainly visited Edinburgh, perhaps more than once, and made close acquaintance with Allan Ramsay, early in the 18nth century, at his shop in the Luckenbooths. Addison's testimony is complete: "He has made the world merry, and I hope they will make him easy so long as he stays among us... They cannot do a kindness to a more diverting companion, or a more cheerful, honest, good-natured man." Again in the Tatler he is praised: "Many an honest gentleman has got a reputation in this country by pretending to have been in the company of Tom D'Urfey. Many a present toast, when she lay in her cradle, has been lulled asleep by D'Urfey's sonnets."[5]

Among his fugitive works was "Collin's Walk through London and Westminster: A poem in burlesque," 1690; and he wrote a "Vive le Roy" for George I in 1714.[5]

Quotations[]

"All animals, except man, know that the principal business of life is to enjoy it."

Recognition[]

Memorial to Durfey at St. James's Church, Piccadilly

At St. James's Church, Piccadilly, where D'Urfey was buried, a Yorkshire slab tablet to his memory was placed on the south wall outside, with the concise inscription, "Tom D'Urfey, dyed Febry ye 26th, 1723."[5]

A good copper-plate portrait of D'Urfey, handsome and good-humoured, in a full-bottomed wig, is prefixed to vol. i. of the ‘Pills,’ 1719, engraved by G. Vertue, after a painting by E. Gouge. E. Gouge adds these lines below the portrait:—

- Whilst D'Urfey's voice his verse does raise,

- When D'Urfey sings his tunefull lays,

- Give D'Urfey's Lyrick Muse the bayes.[5]

In another print, engraved from a sketch taken at Knole, he is represented looking at some music, with 2 large books under his arm.[5]

His poem "Chloe Divine" was included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[6]

His lasting achievement lay in his best songs: 10 of the 68 songs in the The Beggar's Opera were D'Urfey's.

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- A New Collection of Songs and Poems. London: Joseph Hindmarsh, 1683.

- An elegy upon ... Charles II. London: Jo. Hindmarsh, 1685.

- A poem congratulatory on the birth of the young prince. London: Joseph Knight & Francis Saunders, 1688.

- Collin's Walk through London and Westminster: A poem in burlesque. London: Rich. Parker / Abel Roper, 1690; London: John Bullard, 1690.

- New Poems: Consisting of satyrs, elegies, and odes. London: John Bullord / Abel Roper, 1690.

- A Pindarick Ode on New-Year's-Day. London: Abel Roper, 1691.

- A Pindarique Poem on the Royal navy. London: Randall Taylor, 1691.

- Gloriana: A funeral Pindarique poem, sacred to the blessed memory of ... Queen Mary. London: Samuel Briscoe, 1695.

- Albion's blessing. A poem panegyrical on ... King William III. London: W. Onley for Robert Battersby / Thomas Cater, 1698.

- A New Ode; or, dialogue between Mars ... and Plutus. London: 1706.

- Songs Compleat, Pleasant and Divertive. (2 volumes), London: W. Pearson for Jacob Tonson, 1719. Volume I, Volume III, Volume IV, Volume V

- Wit and Mirth; or, Pills to purge melancholy. (6 volumes), London: W. Pearson for Jacob Tonson, 1719-1720. Volume V, Volume VI

- Songs (edited by Thomas Lawrence Day). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933.

- Lewd Songs and Low Ballads of the Eighteenth Century: Bawdy songs From Thomas D'urfey's 'Pills to Purge Melancholy' (1719). Boulder, CO: Bartholomew Press, 1991.

Plays[]

- The Siege of Memphis; or, The ambitious queene: A tragedy. London: W. Cademan, 1676.

- Madam Fickle: or the witty false one. A comedy. London: Thomas Newcomb, for James Magnes & Rich. Bentley, 1677.

- A Fond Husband; or, The plotting sisters: A comedy. London: Thomas Newcomb, for James Magnes & Rich. Bentley, 1677.

- The Fool Turn'd Critick: A comedy. London: James Magnes & Richard Benelty, 1678.

- Trick for Trick; or, The debauch'd hypocrite. A comedy. London: Langley Curtiss, 1678.

- Squire Oldsapp; or, The night-adventures: A comedy. London: James Magnes & Richard Benelty, 1679.

- The Virtuous Wife; or, Good luck at last: A comedy. London: T.N., for R. Bentley & M. Magnes, 1680.

- The Progress of Honesty; or, A view of the court and city. London: Joseph Hindmarsh, 1681.

- Sir Barnaby Whigg; or, No wit like a woman's: A comedy. London: A.G. & J.P. for Joseph Hindmarsh, 1681.

- The Injur'd Princess; or, The fatal wager. London: R. Bentley & M. Magnes, 1682.

- The Royalist: A comedy. London: Joseph Hindmarh, 1692.

- The Malcontent: A satyr: Being the sequel to The progress of honesty. London: Joseph Hindmarsh, 1684.

- The banditti; or, A ladies distress: A play. London: J.B., for R. Bentley, & J. Hindmarsh, 1686.

- The commonwealth of women; a play. London: R. Bentley, & J. Hindmarsh, 1686.

- A Fool's Preferment; or The dukes of Dunstable. A comedy. London: Jos. Knight, and Fra. Saunders, 1688.

- Love for Money; or, The boarding school: A comedy. London: J. Hindemarsh, 1691.

- The Marriage-hater Match'd: a comedy. London: Richard Bentley, 1692.

- The Richmond Heiress; or, A woman once in the right: A comedy. London: Samuel Briscoe, 1693.

- The Comical History of Don Quixote. Part I, London: Samuel Briscoe, 1694; Part II, London: 1694; Part III, London: 1696.

- The Intrigues at Versailles; or, A jilt in all humours: A comedy. London: F. Saunders / P. Buck / R. Parker / et al, 1697.

- A new opera called Cinthia and Endimion; or, the lovers of the deities. London: W. Onley, for Sam. Briscoe / R. Wellington, 1697.

- The Campaigners; or, The pleasant adventures at Brussels: A comedy. London: A. Baldwin, 1698.

- The famous history of the rise and fall of Massaniello; in two parts. London: John Nutt, 1699, 1700.

- The Bath; or, The Western lass. A comedy. London: Peter Buck, 1701.

- Wonders of the Sun; or, The kingdom of the birds. London: Jacob Tonson, 1706.

- The Modern Prophets; or, New wit for a husband: A comedy. London: Bernard Lintott, 1709.

- The Old Mode and the New; or, The country miss with her furbeloe: A comedy. London: Bernard Lintott, 1709.

- The English stage Italianiz'd: In a new dramatic entertainment, called Dido and Aeneas; or, Harlequin. London: Thomas Moore, 1727.

Short fiction[]

- Stories, Moral and Comical. London: Fr. Leach, for Isaac Cleave, 1707.

Collected editions[]

Translated[]

- Madeleine de Scudéry, Zelinda: An excellent new romance. London: T.R. & N.T. for James Magnes / Richard Bentley, 1692.

- Tales Tragical and Comical. From the prose of antique Italian, Spanish, and French authors. London: Bernard Lintott, 1704.

Over The Hills And Far Away (Traditional)

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[7]

See also[]

200. Oh, No, John (Traditional)

References[]

- Cyrus Lawrence Day, "The Songs of Thomas D'Urfey," Harvard Studies in English IX. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933.

Ebsworth, Joseph Woodfall (1888) "D'Urfey, Thomas" in Stephen, Leslie Dictionary of National Biography 16 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 251-255. Wikisource, Web, Jan. 2, 2018.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "D'Urfey, Thomas," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 125. Web, Jan. 2, 2018.

- ↑ Ebsworth, 251.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Ebsworth, 252.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Ebsworth, 253.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Ebsworth, 254.

- ↑ "Chloe Divine", Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 4, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Thomas D'Urfey, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, May 25, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Chloe Divine"

- Thomas D'Urfey at PoemHunter ("Chloe Divine")

- Thomas D'Urey (1653-1723) info & 3 poems at English Poetry, 1579-1830

- Thomas D'Urfey at Poetry Nook (9 poems)

- Books

- Works by Thomas d'Urfey at Project Gutenberg

- Thomas D'Urfey at Amazon.com

- About

- Thomas Durfey in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- The Contemplator's short biography of Thomas D'Urfey (1653-1723)

- "D'Urfey, Thomas" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: D'Urfey, Thomas

|