Allen Ginsberg (1924-1997). Drawing by George Sulzbach. Licensed under Creative Commons.

| Allen Ginsberg | |

|---|---|

| Born |

June 3, 1926 Newark, New Jersey, United States |

| Died | April 5, 1997 (aged 70) |

| Occupation | poet, activist, essayist |

| Literary movement | Beat, New American Poets, Postmodernism |

|

Influences

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (June 3, 1926 - April 5, 1997) was an American poet, best known as a founder of a major literary movement (the Beat Generation) and as a human rights activist.

Life[]

Overview[]

Ginsberg's poetry embodies the countercultural Beat spirit, bringing attention to unconventional subjects and themes. Among his other lifetime passions were world travel, photography, songwriting, and teaching.

His best-known collection, Howl, and other poems, has sold almost a million copies.[1]

Youth and education[]

Ginsberg was born in Newark, New Jersey. Both of his parents belonged to the 1920's New York literary counterculture, their political ideals heavily influenced Ginsberg. His father, Louis, was both a teacher and a poet; his mother, Naomi, suffered from poor mental health for most of her lifetime.

Naomi supported the American Communist Party, and often took Allen to party meetings. Ginsberg later said that his mother's bedtime stories often held the same premise: "The good king rode forth from his castle, saw the suffering workers and healed them."[2] Both her mental health and her social ideology had a tremendous impact on Ginsberg's world perspective.

As a teenager, Ginsberg wrote letters to The New York Times about political issues such as World War II and workers' rights.[2] He began reading poetry, becoming acquainted with and enamored of Walt Whitman's work, and naming Edgar Allan Poe as his favorite poet.

Upon graduating high school in 1943, Ginsberg attended Montclair State University briefly, before entering Columbia University in 1949 on a scholarship from the Young Men's Hebrew Association of Paterson.[3] He began his studies with the initial intent to become a labor lawyer. While at Columbia, Ginsberg contributed to the Columbia Review literary journal and the Jester humor magazine, and served as president of the Philolexian Society, the campus literary and debate group.

As a student at Columbia, he befriended William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac, all members of the eventual Beat movement. Also around this time, Ginsberg experienced an auditory hallucination of William Blake reading his poems "Ah Sunflower," "The Sick Rose," and "Little Girl Lost." He refers to this experience his "Blake vision,” and late often pointed to it as an influential moment in his life and his work, which redefined his understanding of the universe. He believed that he witnessed the interconnectedness of the universe. He looked at lattice work on the fire escape and realized some hand had crafted that; he then looked at the sky and intuited that some hand had crafted that also, or rather that the sky was the hand that crafted itself. He explained that this hallucination was not inspired by drug use, but said he sought to recapture that feeling later with various drugs.[4]

Private life[]

Ginsberg with Peter Orlovsky (1933-2010), 1978. Photo by Herbert Rusche. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Ginsberg's spiritual journey began early on with his spontaneous visions, and continued with an early trip to India. A chance encounter on a New York City street with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (they both tried to catch the same cab), a Tibetan Buddhist meditation master of the Vajrayana school, who became his friend and life-long teacher. Ginsberg helped Trungpa in founding the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado.

In 1954 in San Francisco, Ginsberg met Peter Orlovsky, who remained his life-long companion, and with whom he eventually shared his interest in Tibetan Buddhism.

Ginsberg was also involved with Hinduism. He befriended A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the Hare Krishna movement in the Western world, a relationship that is documented by Satsvarupa Gosvami in his biographical account Srila Prabhupada Lilamrta. Ginsberg donated money, materials, and his reputation to help the Swami establish a temple, and toured with him to promote his cause. Ginsberg also claimed to be the earliest person on the North American continent to chant the Hare Krishna mantra. He was mourned by the Hare Krishnas upon his passing in 1997.

Career[]

Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg, circa 1975. Photo by Elsa Dorfman. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Though he initially intended to become a labor lawyer, Ginsberg wrote poetry for most of his life. His admiration for the writing of Jack Kerouac inspired him to take poetry more seriously. In 1954, Ginsberg moved to San Francisco. Though he took odd jobs to support himself, in 1955, upon the advice of a psychiatrist, Ginsberg dropped out of the working world to devote his entire life to poetry.

He studied under William Carlos Williams, who guided his development and introduced him to other prominent area poets including Kenneth Rexroth and Michael McClure.

With the help of Rexroth, Ginsberg and McClure organized a poetry reading at the new “6” Gallery. The result was "The Six Gallery reading" on October 7, 1955.[5] The event, in essence, brought together the East and West Coast factions of the Beat Generation. That night was the first public reading of Howl, a poem that brought world-wide fame to Ginsberg and many of the poets associated with him. An account can be found in Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums, describing collecting change from each audience member to buy jugs of wine, and Ginsberg reading passionately, drunken, with arms outstretched.

Howl was considered scandalous at the time of its publication due to the rawness of its language, which is frequently explicit. Shortly after Howl, and other poems was published in 1956 by City Lights Bookstore, it was banned for obscenity. The ban became a cause célèbre among defenders of the First Amendment, and was later lifted after Judge Clayton W. Horn declared the poem to possess redeeming social importance. The work became one of the most widely read poems of the century, translated into more than 22 languages.

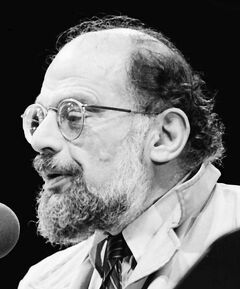

Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997) in 1979. Photo by Hans van Dijk / Anefo. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 1957 Ginsberg left San Francisco, and after a spell in Morocco, he and Orlovsky joined friend Gregory Corso in Paris. Corso introduced them to a shabby lodging house above a bar at 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur that was to become known as the Beat Hotel. They were soon joined by William S. Burroughs and others. It was a productive, creative time for all of them, and it was also a time when Ginsberg began to experiment with drugs as tools for inspiring creative energy. In Paris, Ginsberg finished his epic poem Kaddish, Corso composed "Bomb" and "Marriage," and Burroughs (with Ginsberg’s and Corso’s help) put together Naked Lunch, from previous writings. This period was documented by the photographer Harold Chapman, who moved in at about the same time, and took pictures constantly of the residents of the 'hotel' until it closed in 1963.

In the 1960's, Ginsberg's work became increasingly politically driven, and though he continued to publish his work, his poetry became somewhat overshadowed by his activism. He introduced to Vietnam War protesters the idea of "flower power," whereby protest took the form of promoting values of happiness, love, and peace. Ginsberg also played a key role in ensuring that a 1965 protest of the war — which took place at the Oakland-Berkeley city line and drew several thousand marchers — was not violently interrupted by the California chapter of the notorious motorcycle gang, the Hell's Angels, and their leader, Sonny Barger.

Allen Ginsberg on Late Night, June 10, 1982

His advocacy work extended also to gay rights. Ginsberg was an early proponent of freedom for men who loved other men, having already in 1943 discovered within himself "mountains of homosexuality." He expressed this desire openly and graphically in his poetry. He also struck a note for gay marriage by listing Peter Orlovsky, his lifelong companion, as his spouse in his “Who’s Who” entry. Later homosexual writers saw his frank talk about homosexuality as an opening to speak more openly and honestly about something often before only hinted at or spoken of in metaphor.

Music and chanting were both important parts of Ginsberg's live delivery during poetry readings. He often accompanied himself on a harmonium, and was often accompanied by a guitarist. Attendance at his poetry readings was generally standing room only for most of his career, no matter where he appeared.

Death and burial[]

Allen Ginsberg at Miami Book Fair International, 1985. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Miami Dade College archives and Wikimedia Commons.

Ginsberg had suffered for years from hepatitis, which by 1988 had developed into cirrhosis of the liver. In March 1997, a biopsy revealed the presence of untreatable liver cancer, and he was given 4 months to a year to live.[6]

Ginsberg continued to write through his final illness, writing his last poem, "Things I'll Not Do (Nostalgias)" on March 30, 1997.[7] A collection of his later poetry, including a set of poems written after his cancer diagnosis, was published as Death and Fame: Poems, 1993-1997. A reviewer from Publishers Weekly hailed the volume as "a perfect capstone to a noble life" and said "there has never been an American poet as public as Ginsberg."[8]

Ginsberg died April 5, 1997, surrounded by a group of family and friends in his East Village loft in New York City. He was 70 years old.[9]

Ginsberg is buried in his family plot in Gomel Chesed Cemetery, 1 of a cluster of Jewish cemeteries at the corner of McClellan Street and Mt. Olivet Avenue near the city lines of Elizabeth and Newark, New Jersey.

Writing[]

Most of Ginsberg's very early poetry was written in formal rhyme and meter, like his father or like his idol William Blake, and included archaic pronouns like "thee." Ginsberg’s mentor, Williams, hated most of his early poems; Williams told Ginsberg later, "In this mode perfection is basic, and these poems are not perfect." He taught Ginsberg not to emulate the old masters but to speak with his own voice and the voice of the common American. Williams taught him to focus on strong visual images, in line with Williams' own motto, "No ideas but in things." His time studying under Williams led to a tremendous shift from the early formalist work to the brilliance of his later work. Early breakthrough poems include "Bricklayer's Lunch Hour" and "Dream Record."

Ginsberg's poetry was strongly influenced by modernism (specifically Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Hart Crane, and most importantly Williams), Romanticism (specifically Percy Shelley and John Keats), the beat and cadence of jazz (specifically that of bop musicians such as Charlie Parker), and his Kagyu Buddhist practice and Jewish background. He considered himself to have inherited the visionary poetic mantle handed down from English poet and artist William Blake and American poet Walt Whitman. The power of Ginsberg's verse, its searching, probing focus, its long and lilting lines, as well as its New World exuberance, all echo the continuity of inspiration which he claimed.

Ginsberg also intensively studied haiku and the paintings of Paul Cezanne, from which he adapted a concept important to his work, which he called the "Eyeball Kick." He noticed in viewing Cezanne's paintings that when the eye moved from one color to a contrasting color, the eye would spasm, or "kick." Likewise, he discovered that the contrast of 2 seeming opposites was a common feature in haiku. Ginsberg used this technique in his poetry, putting together 2 starkly dissimilar images: something weak with something strong, an artifact of high culture with an artifact of low culture, something holy with something unholy. The example Ginsberg most often used was "hydrogen jukebox" (which later became the title of an opera he wrote with Philip Glass).

Like Williams, Ginsberg's line breaks were often determined by breath: one line in Howl, for example, should be read in one breath. Ginsberg claimed he developed such a long line because he had long breaths (saying perhaps it was because he talked fast, or he did yoga, or he was Jewish). The famous long line could also be traced back to his study of Whitman; Ginsberg claimed Whitman's long line was a dynamic technique few other poets had ventured to develop further. Ginsberg also commonly employed catachresis. For example, from Howl: "secret gas station solipsisms of johns" is perhaps designed to make 'solipsism' sound like a sexual act. Another example is "what peaches and what penumbra" from "Supermarket in California" is perhaps designed to make penumbra seem like a fruit or like something you can buy in a supermarket.

Ginsberg claimed throughout his life that his biggest inspiration was Kerouac's concept of “spontaneous prose.” He believed literature should come from the soul without conscious restrictions. However, Ginsberg was much more prone to revise than Kerouac. For example, when Kerouac saw the first draft of Howl he disliked the fact that Ginsberg had made editorial changes in pencil (transposing "negro" and "angry" in the first line, for example). Kerouac only wrote out his concepts of “spontaneous prose” at Ginsberg's insistence because Ginsberg wanted to learn how to apply the technique to his poetry.

Ginsberg developed an individualistic, easily identifible style. Howl came out during a potentially hostile literary environment less welcoming to poetry outside of tradition; there was a renewed focus on form and structure among academic poets and critics partly inspired by New Criticism. Consequently, Ginsberg often had to defend his choice to break away from traditional poetic structure, often citing Williams, Pound, and Whitman as precursors.

Ginsberg's style may have seemed to critics chaotic or unpoetic, but to Ginsberg it was an open, ecstatic expression of thoughts and feelings that were naturally poetic. He believed strongly that traditional formalist considerations were archaic and didn't apply to reality. Though some, Diana Trilling for example, have pointed to Ginsberg's occasional use of meter (for example the anapest of "who came back to Denver and waited in vain"), Ginsberg denied any intention toward meter and claimed instead that meter follows the natural poetic voice, not the other way around; he said, as he learned from Williams, that natural speech is occasionally dactylic, so poetry that imitates natural speech will sometimes fall into a dactylic structure but only ever accidentally.

Howl[]

Ginsberg is best known for Howl (1956), an epic poem about the self-destruction of his friends of the Beat Generation and what he saw as the destructive forces of materialism and conformity in the United States at the time.

An important figure when considering inspiration for Howl is Carl Solomon, to whom the poem is dedicated. Solomon was a Dada and surrealism enthusiast (he introduced Ginsberg to Antonin Artaud) who suffered bouts of depression. Solomon wanted to commit suicide, but he thought a form of suicide appropriate to dadaism would be to go to a mental institution and demand a lobotomy. The institution refused, giving him many forms of therapy, including electroshock therapy. Much of the final section of part I of Howl is a description of this.

Ginsberg used Solomon as an example of all those ground down by the machine of "Moloch." Ginsberg said the image of Moloch was inspired by peyote visions he had of the Francis Drake Hotel in San Francisco which appeared to him as a skull; he took it as a symbol of the city (not specifically San Francisco, but all cities). Moloch has subsequently been interpreted as any system of control, including the conformist society of post-World War II America focused on material gain, which Ginsberg frequently blamed for the destruction of all those outside of societal norms.

Kaddish[]

While Howl remains Ginsberg's most legendary work, Kaddish perhaps equaled Howl in epic scope and accomplishment. Written as an elegy, it was intended to be a tribute to his mother, and in it Ginsberg recounted their relationship and the emotional impact that her mental troubles had on him and his family.

Recognition[]

As a student at Columbia, Ginsberg won the Woodberry Poetry Prize.

Ginsberg won the National Book Award for his book The Fall of America. In 1993, the French minister of culture awarded him the medal of “Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres” (the “Order of Arts and Letters”). He was named a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College and he also helped found and direct the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in Colorado.

Publications[]

- Howl, and other poems (with introduction by William Carlos Williams ). San Francisco: City Lights, 1956

- (revised edition) Grabhorn-Hoyem, 1971

- (40th anniversary edition) City Lights, 1996.

- Siesta in Xbalba and Return to the States. privately printed, 1956.

- Kaddish, and other poems, 1958-1960. San Francisco: City Lights, 1961.

- Empty Mirror: Early poems. Chevy Chase, MD: Corinth Books, 1961, 1970.

- A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley. Grabhorn Press, 1963.

- Reality Sandwiches: 1953-1960. City Lights, 1963.

- The Change. Writer's Forum, 1963.

- Kral Majales (title means "King of May"). Kensington, CA: Oyez, 1965.

- Wichita Vortex Sutra. London: Housmans, 1966; Brunswick, ME: Coyote Books, 1967.

- TV Baby Poems. Cape Golliard Press, 1967, Grossman, 1968.

- Airplane Dreams: Compositions from journals. Toronto: Anansi, 1968; San Francisco: City Lights, 1969.

- Ankor Wat (with Alexandra Lawrence). Fulcrum Press, 1968.

- Scrap Leaves, Tasty Scribbles. Poet's Press, 1968.

- Wales: A visitation, July 29, 1967. Cape Golliard Press, 1968.

- The Heart Is a Clock. Gallery Upstairs Press, 1968.

- Message II. Gallery Upstairs Press, 1968.

- Planet News. City Lights, 1968.

- For the Soul of the Planet Is Wakening... Desert Review Press, 1970.

- The Moments Return: A poem. Grabhorn-Hoyem, 1970.

- Ginsberg's Improvised Poetics (edited by Mark Robison). Anonym Books, 1971.

- New Year Blues. New York: Phoenix Book Shop, 1972.

- Open Head. Melbourne, Victoria: Sun Books, 1972.

- Bixby Canyon Ocean Path Word Breeze. New York: Gotham Book Mart, 1972.

- Iron Horse. Chicago: Coach House Press (Chicago), 1972.

- The Fall of America: Poems of these states, 1965-1971. City Lights, 1973.

- The Gates of Wrath: Rhymed poems, 1948-1952. San Francisco: Grey Fox, 1973.

- Sad Dust Glories: Poems during work summer in woods, 1974. Seattle, WA: Workingman's Press, 1975.

- First Blues: Rags, ballads, and harmonium songs, 1971-1974. New York: Full Court Press, 1975.

- Mind Breaths: Poems, 1972-1977. City Lights, 1978.

- Poems All over the Place: Mostly seventies. Wheaton, MD: Cherry Valley, 1978.

- Mostly Sitting Haiku. Fanwood, NJ: From Here Press, 1978

- revised & expanded, 1979.

- Careless Love: Two rhymes. Red Ozier Press, 1978.

- Straight Hearts' Delight: Love poems and selected letters (with Peter Orlovsky). San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1980.

- Plutonian Ode: Poems, 1977-1980. City Lights, 1982.

- Collected Poems, 1947-1980. New York: Harper, 1984.

- (expanded edition) Collected Poems: 1947-85. New York: Penguin, 1995.

- Many Loves. Pequod Press, 1984.

- Old Love Story. Lospecchio Press, 1986.

- White Shroud. Harper, 1986.

- Cosmopolitan Greetings: Poems, 1986-1992. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

- Illuminated Poems (illustrated by Eric Drooker). New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1996.

- Selected Poems, 1947-1995. HarperCollins, 1996.

- Death and Fame: Poems, 1993-1997 (edited by Bob Rosenthal, Peter Hale, and Bill Morgan, with foreword by Robert Creeley). New York: HarperFlamingo, 1999.

- Wait Till I'm Dead: Uncollected poems (edited by [Bill Morgan, with introduction by Rachel Zucker). New York: Grove Press, 2016.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[10]

Audio / video[]

Poetry Breaks Allen Ginsberg Reads "A Supermarket in California"

Allen Ginsberg Reading Howl (Part 1)

Allen Ginsberg's LSD poem to William Buckley

Allen Ginsberg Reads Beat Poetry at Royal Albert Hall London 1965

Allen Ginsberg reads America

- Allen Ginsberg Reading (LP). Berkeley, CA: Fantasy, 1959.

- Allen Ginsberg reads Kaddish. (LP) New York: Atlantic, 1966; (CD) New York: Water, 2006.

- Allen Ginsberg and the Daily Planet (LP). New York: EMR Enterprises, 1969.

- Ginsberg's Thing (LP). New York: Douglas, 1970.

- Allen Ginsberg Live!. San Francisco: S Press, 1976.

- Allen Ginsberg Reading (cassette). Boulder, CO: Naropa Institute, 1980.

- Allen Ginsberg on KPFK, 1985 (cassette). Mill Valley, CA: Sound Photosynthesis, 1985.

- Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems and songs, 1949-1993 (CD). Los Angeles: Rhino / Word Beat, 1994.

- The Lion for Real (CD). New York: Mercury 1997.

- Howl, and other poems (CD). Berkeley, CA: Fantasy, 1998.

- Allen Ginsberg (CD). New York: Random House Audio, 2004.

- The Allen Ginsberg Audio Collection (CD). New York: Caedmon, 2004.

Except where noted, discographical information courtesy the WorldCat.[11]

See also[]

References[]

- Bullough, Vern L. "Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context." Harrington Park Press, 2002.

- Charters, Ann (ed.). The Portable Beat Reader. New York: Penguin Books, 1992. ISBN 0140151028

- Clark, Thomas. "Allen Ginsberg." Writers at Work—The Paris Review Interviews.

- Gifford, Barry (ed.). As Ever: The Collected Letters of Allen Ginsberg & Neal Cassady. Berkeley: Creative Arts Books, 1977. ISBN 0916870081

- Hrebeniak, Michael. Action Writing: Jack Kerouac's Wild Form. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2006. ISBN 0809326949

- Miles, Barry. Ginsberg: A Biography. London: Virgin Publishing Ltd., 2001. ISBN 0753504863

- Podhoretz, Norman. "At War with Allen Ginsberg," in Ex-Friends. New York: Free Press, 1999. ISBN 0684855941

- Raskin, Jonah. American Scream: Allen Ginsberg's Howl and the Making of the Beat Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 0520240154

- Schumacher, Michael (ed.). Family Business: Selected Letters Between a Father and Son. Bloomsbury, 2002. ISBN 1582342164

- Schumacher, Michael. Dharma Lion: A Biography of Allen Ginsberg. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994. ISBN 0312112637

- Trigilio, Tony. "Strange Prophecies Anew": Rereading Apocalypse in Blake, H.D., and Ginsberg. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2000. ISBN 0838638546

- Trigilio, Tony. Allen Ginsberg's Buddhist Poetics. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007. ISBN 0809327554

- Tytell, John. Naked Angels: Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1976. ISBN 1566636833

- Warner, Simon (ed.). Howl for Now: A 50th Anniversary Celebration of Allen Ginsberg's Epic Protest Poem. West Yorkshire, UK: Route, 2005. ISBN 1901927253

Fonds[]

- Allen Ginsberg papers, 1937 - 1994 housed at the Stanford University Libraries

- Allen Ginsberg film and video archive, 1983 - 1996 housed at the Stanford University Libraries

Notes[]

- ↑ "Birth of the Beat generation: 45th anniversary of "Howl" read at Six Gallery," San Francisco Chronicle, October 28, 2000, UPenn.edu, Web, July 20, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bonesy Jones, The Biography Project: Allen Ginsberg, Popsubculture.com. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- ↑ Wilborn Hampton, “Allen Ginsberg, Master Poet of Beat Generation, Dies at 70,” New York Times (April 6, 1997). Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- ↑ Barry Miles, Ginsberg: A Biography (London: Virgin Publishing Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0753504863).

- ↑ Robert Siegel, “Birth of the Beat Generation: 50 Years of 'Howl',” National Public Radio (Oct. 7, 2005). Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Steve Silberman, Allen Ginsberg dying of liver cancer," Wired, April 3, 1997. Web, Mar. 15, 2019.

- ↑ Allen Ginsberg, Collected Poems. 1947-1997, 1160-1161.

- ↑ "Allen Ginsberg," Contemporary Authors Online (Gale, 2004).

- ↑ Death of Allen Ginsberg, Tributes.com. Web, mar. 15, 2019.

- ↑ Allen Ginsberg 1926-1997, Poetry Foundation, Web, July 15, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Allen Ginsberg, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Oct. 11, 2015.

External links[]

- Poems

- "A Supermarket in California"

- Full text of "Howl" at wussu.

- Allen Ginsberg profile & 5 poems at the Academy of American Poets.

- Allen Ginsberg 1926-1997 at the Poetry Foundation.

- Online Poems by Allen Ginsberg

- Allen Ginsberg at PoemHunter (47 poems)

- Prose

- Audio / video

- Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997) at The Poetry Archive

- Allen Ginsberg reads "Howl"

- Links, streaming audio & video

- Allen Ginsberg at YouTube

- Allen Ginsberg at Vimeo

- Books

- Allen Ginsberg at Amazon.com

- About

- Allen Ginsberg at The Beat Page

- Allen Ginsberg at Biography.com

- Allen Ginsberg at NNDB

- Allen Ginsberg at Find a Grave

- Allen Ginsberg Official website

- The Allen Ginsberg Project weblog

- "After 50 Years, Ginsberg's 'Howl' Still Resonates" by John McChesney, NPR

This article uses text from the New World Encyclopedia.

|