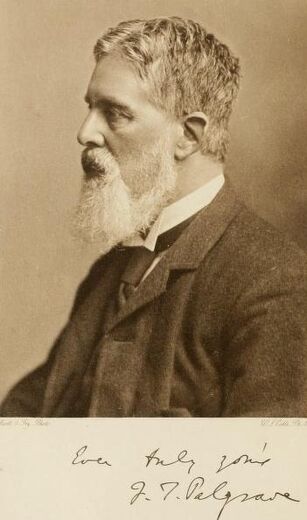

Francis Turner Palgrave (1824-1897), from His journals and memories of his life, 1899. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Francis Turner Palgrave (28 September 1824 - 24 October 1897) was an English poet, literary critic, anthologist, and academic.

Life[]

Overview[]

Palgrave, son of Sir Francis Palgrave, was educated at Oxford, was for many years connected with the Education Department, of which he rose to be assistant secretart; and from 1886-95 he was professor of poetry at Oxford. He wrote several volumes of poetry, including Visions of England (1881), and Amenophis (1892), which, though graceful and exhibiting much poetic feeling, were the work rather of a man of culture than of a poet. His great contribution to literature was his anthology, The Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics (1864), selected with marvellous insight and judgment. A 2nd series showed these qualities in a less degree. He also published an anthology of sacred poetry.[1]

Youth[]

Palgrave was the eldest son of historian and antiquary Sir Francis Palgrave (born Myron Cohen, 1788-1861). He was born at Great Yarmouth, in the house of his maternal grandfather, Dawson Turner, a banker of that town, on 28 September 1824. His childhood was spent partly there, but chiefly in his father's suburban residence at Hampstead.[2]

He grew up, in both houses, amid an atmosphere of high artistic culture and strenuous thought. He was familiar from infancy with collections of books, pictures, and engravings, and when he visited Italy with his parents at the age of 14, was already capable of appreciating, and being profoundly influenced by, what he saw there both in art and nature. This gravity and sensibility beyond his years was further reinforced by the fervid anglo-catholicism of his family.[2]

His earlier education was at home; he was afterwards (1838-43) a day boy at Charterhouse, from which in 1842 he gained a scholarship at Balliol College, Oxford, and went into residence there in 1843. There he joined the brilliant circle which included Arnold, Clough, Doyle, Sellar, and Shairp, and which has been commemorated by the last-named of these in the posthumous volume of poems entitled Glen Desseray (prefaced and edited by Palgrave himself 40 years later).[2]

Palgrave took a 1st class in classics in 1847, having already, some months previously, been elected a fellow of Exeter College; he did not graduate until 1856, when he earned both a B.A. and an M.A.[2]

Career[]

Palgrave by Samuel Lawrence (1812-1884), 1872. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Early in 1846 Palgrave had been engaged for some months as assistant private secretary to W.E. Gladstone, then secretary of state for war and the colonies. Soon after completing his probationary year at Exeter he returned to the public service by accepting an appointment under the education department, in which the rest of his active life was spent.[3]

From 1850 to 1855 he was vice-principal, under Dr. Temple (later archbishop of Canterbury), of Kneller Hall, a government training college for elementary teachers at Twickenham. Tennyson was then living in the neighborhood, and the acquaintance begun in 1849 between the 2 grew into a warm and lasting friendship. In 1854 Palgrave published Idyls and Songs, a small volume of poems which has not achieved permanence.[3]

In 1855 Palgrave returned to London on the discontinuance of the training college, and served in Whitehall, as examiner and then as assistant secretary of the education department, until his retirement in 1884.[3]

He was for several years art critic to the Saturday Review, and contributed a large number of reviews and critical essays dealing with art and literature to the Quarterly Review and other periodicals.[3]

During annual holidays spent with Tennyson in England or abroad, the scheme and contents of the Golden Treasury were now being evolved. It was published in 1861, and obtained an immediate and decisive success which has continued for 40 years.[3]

In 1862 Palgrave was employed in the revision of the official catalogue of the fine art department of the exhibition of that year, and the compilation of a descriptive handbook to the art collections there.[3] There was a minor scandal in 1862 when Palgrave was commissioned to write a catalogue for the 1862 International Exhibition, in which he praised his friend, sculptor Thomas Woolner, and denigrated other sculptors, especially Woolner's main rival Carlo Marochetti. The well known controversialist Jacob Omnium pointed out in a series of letters to the press that the 2 men lived together. William Holman Hunt wrote a reply supporting Palgrave and Woolner,[4] but Palgrave was forced to withdraw the catalogue.

Palgrave married, in December 1862, Cecil, daughter of J. Milnes Gaskell, M.P., who predeceased him on 27 March 1890, and left surviving him a son and 4 daughters.[5]

Also in 1862 he wrote a memoir of Clough, who had died the autumn before. In 1866 he published a volume of Essays on Art, and a critical biography of Scott prefixed to a collected edition of his poems. Among other productions of this period were an edition of Shakespeare's Poems (1865), a volume of Stories for Children (1868), and another of Lyrical Poems (1871).[3] He published a small collection of Hymns in 1867 which ran to 3 editions, each slightly enlarged.[6]

The Children's Treasury of English Song, a companion volume for children to the Golden Treasury, and the result, like it, of many years of thought and selection, appeared in 1875. The other anthologies made by him may be mentioned (here together: Chrysomela, a volume of selections from Robert Herrick (1877), Tennyson's Select Lyrics (1885), and the Treasury of Sacred Song (1889).

2 more volumes of original poems, the Visions of England (1881) and Amenophis (1892), complete the list of his own contributions to English poetry.[3]

Last years[]

In 1884 Palgrave resigned his assistant secretaryship in the education department. The remainder of his life was divided between London and the country house at Lyme Regis which he had bought in 1872, with almost annual visits to Italy.[3]

In 1885 he was elected to the professorship of poetry at Oxford, vacated by the death of John Campbell Shairp. He had already declined to be put in nomination for that chair in 1867 as Arnold's successor, and had actually been a candidate in 1877, but had withdrawn then in Shairp's favour. He held the chair for 2 quinquennial terms, 1885-1895.[3]

A 2nd series of the Golden Treasury, the response to many appeals for inclusion of later poets, was published only in the year before his death. In it the selection made failed to give general satisfaction; and indeed the judgments in poetry of a man of 70 are likely to have lost much and gained little in the years of declining life. By that time too the way he had opened 35 years before was thronged with followers, and the new volume took a place only as 1 among the crowd.[3]

A volume of his Oxford lectures, Landscape in Poetry (1897), collected and revised by him after he vacated the chair, was Palgrave's last published work.[5]

Palgrave was one of those men whose distinction and influence consist less in creative power than in that appreciation of the best things which is the highest kind of criticism, and in the habit of living, in all matters of both art and life, at the highest standard. This quality, which is what is meant by the classical spirit, he possessed to a degree always rare, and perhaps more rare than ever in the present age. Beyond this, but not unconnected with it, were qualities which only survive in the memory of his friends childlike transparency of character, affectionateness, and quick human sympathy.[5]

His health had been for some years failing, and he died after a brief illness on 24 October 1897.[5]

Writing[]

Poet[]

Much of the inner history and not a little also of the outward incident of his life up to its time is recorded in the remarkable volume published by him pseudonymously in 1858, under the title of The Passionate Pilgrim, the Dichtung und Wahrheit of a highly cultured and delicately sensitive mind. The work is now little known, but is notable for the mingled breadth and subtlety of its psychology, and is only marred by a slight overloading of quotation. This was, however (and the same may be said of much of his later writing), no ostentation of learning, but the natural overflow of unusual knowledge and a power of critical appreciation which was in excess of his own creative faculty. Here, as so often elsewhere, the imaginative precocity fostered in him by his early surroundings had to be paid for by a certain lack of sustained force in his mature work.[3]

His Visions of England (1880–1881) has dignity and lucidity, but little of the "natural magic" which the greatest of his predecessors in the Oxford chair considered rightly to be the test of inspiration.

Critic[]

Palgrave published both criticism and poetry, but his work as a critic was by far the more important. His criticism is considered to demonstrate fine and sensitive tact, quick intuitive perception, and generally sound judgment.

His Handbook to the Fine Arts Collection, International Exhibition, 1862, and his Essays on Art (1866), though flawed, were full of striking judgments strikingly expressed. His Landscape in Poetry (1897) showed wide knowledge and critical appreciation of one of the most attractive aspects of poetic interpretation.

Anthologist[]

But Palgrave's principal contribution to the development of literary taste was contained in his Golden Treasury of English Songs and Lyrics (1861), an anthology of the best poetry in the language constructed upon a plan sound and spacious, and followed out with a delicacy of feeling which could scarcely be surpassed.

The enterprise had often been attempted before, and often renewed since; but Palgrave's at once blotted out all its predecessors, and retains its primacy among the large and yearly increasing ranks of similar or cognate volumes towards which it has given the 1st stimulus. In itself it is, like all anthologies, open to criticism both for its inclusions and its omissions. In later editions some of these criticisms were admitted and met by Palgrave himself. But it remains a rare instance in which critical work has a substantive imaginative value, and entitles its author to rank among creative artists.[3]

Recognition[]

In 1878 he had been made an honorary LL.D. of Edinburgh University.[3]

In 1885 he was elected Oxford Professor of Poetry. He held the chair for 2 5-year terms, 1885-1895.[3]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Idyls and Songs, 1848-1854. London: J.W. Parker, 1854.

- Hymns. London: Macmillan, 1868; New York: A.D.F. Randolph, 1868.

- Lyrical Poems. London & New York: Macmillan, 1871.

- A Lyme Garland: Being verses, mainly written at Lyme Regis, or upon the scenery of the neighbourhood. Lyme, UK: Printed for the school fund by Dunster, 1874.

- Ode for the Twenty-first of June, 1887 (chapbook). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1887.

- Amenophis, and other poems: Sacred and secular. London & New York: Macmillan, 1892.

Fiction[]

- The Passionate Pilgrim; or, Eros and Anteros (as "Henry J. Thurston"). London: Chapman & Hall, 1858.

- London: P. Davies, 1924.

Non-fiction[]

- Essays on Art. Cambridge, UK, & London: Mamillan, 1866.

- Landscape in poetry from Homer to Tennyson: With many illustrative examples. London & New York: Macmillan, 1897.

Juvenile[]

- The Five Days' Entertainments at Wentworth Grange. London: Macmillan, 1868.

Edited[]

- The Golden Treasury: Of the best songs and lyrical poems in the English language. Cambridge, UK, & London: Macmillan, 1861.

- revised and expanded as The Golden Treasury of the Best Songs and Lyrical Poems in the English language: Together with one hundred additional poems (to the end of the nineteenth century). London & New York: Oxford University Press, 1921.

- Palgrave's "The Golden Treasury": To which is appended the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. New York: Modern Library, 1944.

- The Children's Treasury of Lyrical Poetry. London & New York: Macmillan, 1875.

- The Children's Treasury of English Song. New York: Macmillan, 1875.

- The Visions of England. London: Macmillan, 1881.

- Robert Herrick, Chrysomela: A selection from the lyrical poems of Robert Herrick. London & New York: Macmillan, 1892.

- The Treasury of Sacred Song: Selected from the English lyrical poetry of four centuries. Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1899.

- Poems of Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats: Selected from "The golden treasury" of Francis Turner Palgrave. Boston: Ginn, 1914.

Letters and journals[]

- Francis Turner Palgrave: His journals and memories of his life (edited by Gwenllian Florence Palgrave). London, New York & Bombay: Longmans Green, 1899.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[7]

See also[]

| Preceded by John Campbell Shairp |

Oxford Professor of Poetry 1885-1895 |

Succeeded by William John Courthope |

References[]

- Gwenllian F. Palgrave, Francis Turner Palgrave: His journals and memories of his life. New York: Longmans, Green, 1899.

Mackail, John William (1901). "Palgrave, Francis Turner". In Sidney Lee. Dictionary of National Biography, 1901 supplement. 3. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 242-244.. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 18, 2018.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Palgrave, Francis Turner," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 294. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 18, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Mackail, 242.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Mackail, 243.

- ↑ James H. Coombs, A Pre-Raphaelite friendship: The correspondence of William Holman Hunt and John Lucas Tupper, UMI Research Press, 1986, p.133.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Mackail, 244.

- ↑ Palgrave, Francis Turner (1867). Hymns. London: Macmillan. pp. 34.

- ↑ Search results = au:Francis Turner Palgrave, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Oct. 19, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- "The City of God"

- "The Golden Land"

- Francis Turner Palgave at Poets' Corner (6 poems)

- Palgrave in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "The Ancient and Modern Muses," "Pro Mortuis," "William Wordsworth," "A Little Child's Hymn," "A Danish Barrow"

- Francis Turner Palgrave at Hymnary (profile & 20 hymns)

- Francis Turner Palgrave at Poetry Nook (38 poems)

- Francis Turner Palgrave at PoemHunter (58 poems)

- Books

- Works by Francis Turner Palgrave at Project Gutenberg

- Francis Turner Palgrave at Amazon.com

- About

- Francis Turner Palgrave in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Francis Turner Palgrave in NNDB

- F.T. Palgrave in the Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- Francis Turner Palgrave in The Sacred Poets of the Nineteenth Century

- Francis Turner Palgrave in Twickenham

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Palgrave, Francis Turner

|