Isabella Valancy Crawford (1850-1887), from Canadian Singers and their Songs, 1919. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Isabella Valancy Crawford (December 25, 1850 - February 12, 1887) was an Irish-born Canadian poet and prose writer. "Crawford is increasingly being viewed as Canada's first major poet."[1] She is the author of "Malcolm's Katie," a poem that has achieved "a central place in the canon of nineteenth-century Canadian poetry."[2]

Life[]

Much of Crawford's early life is unknown; "so little remains of the usual sources of evidence. We have no interviews with the subject or with those who knew her; we have no letters, diaries, or journals.... Some of the most basic questions about her life are likely to remain unanswered."[3]

By her own account she was born in Dublin, Ireland, the 6th daughter of Dr. Stephen Dennis Crawford and Sydney Scott; but "No record has been found of that marriage or of the birthdates and birthplaces of at least six children, of whom Isabella wrote that she was the sixth."[4]

The family was in Canada by 1857; in that year, Dr. Crawford applied for a license to practice medicine in Paisley, Ontario (or Canada West, as it was then called).[3] "In a few years, disease had taken nine of the twelve children, and a small medical practice had reduced the family to semi-poverty."[5] Dr. Crawford served as Treasurer of Paisley Township, but "a scandal of a missing $500 in misappropriated Township funds and the subsequent suicide of one of his bondsmen" caused the family to leave Paisley in 1861.[3]

By chance Dr. Crawford met Richard Strickland of Lakefield. Strickland invited the Crawfords to live at his home, out of charity, and because Lakefield did not have a doctor. There the family became acquainted with Strickland's sisters, writers Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill.[4] Isabella Crawford reportedly began writing at that time.[3] She was also "thought to be" a close companion of Mrs. Traill's daughter, Katharine (Katie).[4]

In 1869 the family moved to Peterborough, and Crawford began to write and publish poems and stories.[6] Her first published poem, "A Vesper Star," appeared in The Toronto Mail on Christmas Eve, 1873.[4]

"When Dr. Crawford died, on 3 July 1875, the three women" – Isabella, her mother, and her sister Emma, all who were left in the household – "became dependent on Isabella's literary earnings."[4] After Emma died of tuberculosis, "Isabella and her mother moved in 1876 to Toronto, which was the centre of the publishing world in Canada."[3]

"Although Isabella had been writing while still living in Lakefield ... and had published poems in Toronto newspapers and stories in American magazines while living in Peterborough, when she moved to Toronto she turned her attention in earnest to the business of writing."[3] "During this productive period she contributed numerous serialized novels and novellas to New York and Toronto publications,"[6] "including the Mail, the Globe, the National, and the Evening Telegram.[1] She also contributed "a quantity of 'occasional' verse to the Toronto papers ... and articles for the Fireside Monthly. In 1886 she became the first local writer to have a novel, A little Bacchante, serialized in the Evening Globe.[4]

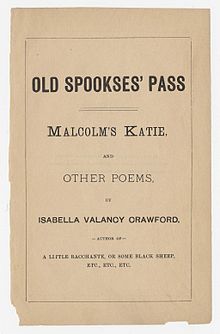

In her lifetime Crawford published only 1 book, Old Spookses' Pass, Malcolm's Katie, and other poems in 1884. It was privately printed and sold poorly.[6] Crawford paid for the printing of 1,000 copies, and presumably sent out many review copies; "there were notices in such London journals as the Spectator, the Graphic, the Leisure Hour, and the Saturday Review. These articles pointed to 'versatility of talent,' and to such qualities as 'humour, vivacity, and range of power,' which were impressive and promising despite her extravagance of incident and 'untrained magniloquence.'"[4] However, only 50 books sold. "Crawford was understandably disappointed and felt she had been neglected by 'the High Priests of Canadian Periodical Literature'" (Arcturus 84)."[1]

Crawford "died, in poverty, on February 12, 1887" in Toronto.[7] She was buried in Peterborough's Little Lake Cemetery near the Otonabee River.[8]

Writing[]

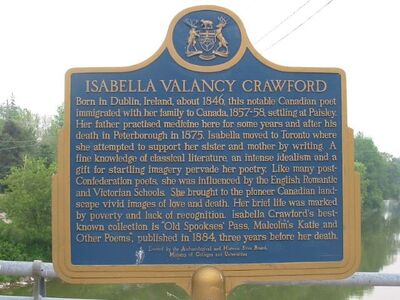

Isabella Valancy Crawford plaque in Paisley, Ontario. Photo by Alan L. Brown, June 2005. Photo used with permission from the website Ontario's Historical Placques (www.ontarioplaques.com).

Prose[]

While Crawford was a prolific writer, much of what she wrote is disposable. "For the most part Crawford's prose followed the fashion of the feuilleton of the day."[4] Her magazine writing "displays a skilful and energetic use of literary conventions made popular by Dickens, such as twins and doubles, mysterious childhood disappearances, stony-hearted fathers, sacrificial daughters, wills and lost inheritances, recognition scenes, and, to quote one of her titles, 'A kingly restitution'."[9] As a whole, though, it "was romantic-Gothic 'formula fiction.'"[4]

Poetry[]

It is her poetry that has endured. Just 2 years after her death, W.D. Lighthall included generous selections from her book in his groundbreaking 1889 anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion, bringing it to a wider audience.

"In the 20th century critics have given the work increasing respect and appreciation."[4] "Crawford's Collected Poems were edited (Toronto 1905) by J.W. Garvin, with an introduction by Ethelwyn Wetherald," a popular Canadian poet.[7] Wetherald called Craword "purely a genius, not a craftswoman, and a genius who has patience enough to be an artist." In his 1916 anthology, Canadian Poets, Garvin stated that Crawford was "one of the greatest of women poets."[5] Poet Katherine Hale, Garvin's wife, published a volume on Isabella Valancy Crawford in the 1920s Makers of Canada series.[1] All of this helped Crawford's poetry become more widely known.

A "serious critical assessment began in the mid-1940's with A.J.M. Smith, Northrop Frye, and E.K. Brown (who called her 'the only Canadian woman poet of real importance in the last century')."[1] "Recognition of Isabella Valancy Crawford's extraordinary mythopoeic power, and her structural use of images, came ... in James Reaney's lecture "Isabella Valancy Crawford" in Our living tradition (series 3, 1959)." [9] Then a "renewed interest in Crawford resulted in the publication of forgotten manuscripts and critical articles" in the 1970s.[6] "A reprint of the collected poems in 1972, with an introduction by poet James Reaney, made Crawford's work generally available; six of her short stories, edited by Penny Petrone, appeared in 1975; and in 1977 the Borealis Press published a book of fairy stories and a long unfinished poem, 'Hugh and Ion.'."[4]

Crawford wrote in a wide variety of forms and styles, ranging from the Walter Scott-like ballad doggerel (pun intended) of "Love Me, Love My Dog", to the eerie mysticism of "The Camp of Souls," to the eroticism of "The Lily Bed." But it is mainly her "long narrative poems [that] have received particular attention."[6]

"'Old Spookses' Pass' is a dialect poem, set in the Rocky Mountains, concerning a dream vision of a midnight cattle stampede towards a black abyss that is stilled by a whirling lariat; 'The helot' makes use of the Spartans' practice of intoxicating their helots in order to teach their own children not to drink, as the starting-point for a highly incantatory and hypnotic poem that ends in Bacchic possession and death; and 'Gisli the Chieftain' fuses mythic elements, such as the Russian spring goddess Lada and the Icelandic Brynhild, into a narrative of love, betrayal, murder, and reconciliation. These poems follow a pattern of depicting the world as a battleground of opposites — light and dark, good and evil — reconciled by sacrificial love."[9]

Malcolm's Katie[]

The bulk of critical attention has gone to "Malcolm's Katie." That poem is a long narrative in blank verse, dealing mainly with the love and trials of young Max and Katie in the 19th-century Canadian bush, but containing a second running narrative recounting the war between the North and South Winds (Winter and Summer personified as First Nations warriors), and also a collection of love songs in different stanza forms.

Many of those lauding the poem have seen their own interests reflected in it. For instance, socialist Livesay gave a reading that made the poem sound like a manifesto of Utopian socialism:

- Crawford presents a new myth of great significance to Canadian literature: the Canadian frontier as creating 'the conditions for a new Eden,' not a golden age or a millennium, but 'a harmonious community, here and now.' Crawford's social consciousness and concern for humanity's future committed her, far ahead of her time and milieu, to write passionate pleas for brotherhood, pacifism, and the preservation of a green world. Her deeply felt belief in a just society wherein men and women would have equal status in a world free from war, class hatred, and racial prejudice dominates all her finest poetry."[4]

Others have similarly seen their concerns reflected in the poem. "Malcolm's Katie has been given a nationalistic reading by Robin Mathews, a feminist reading by Clara Thomas, a biographical reading by Dorothy Farmiloe and a Marxian reading by Kenneth Hughes, as well as various literary-historical readings by Dorothy Livesay, Elizabeth Waterston, John Ower, Robert Alan Burns and others."[2]

Not just interpretations on the poem's meaning, but evaluations of its worth, have varied widely. Its detractors have included poet Louis Dudek, who called Crawford "'a failed poet' of 'hollow convention ... counterfeit feeling ... and fake idealism'"; and Roy Daniells, who in The Literary History of Canada (1965) called "Malcolm's Katie" "a preposterously romantic love story on a Tennysonian model in which a wildly creaking plot finally delivers true love safe and triumphant." [2]

Some of the poem's supporters concede the Tennyson influence but point out that there is much more to it: "While appearing on the surface melodramatic and stereotyped, Crawford's love story is compelling and powerful; what seems at first a conventional conflict between rival suitors for the hand of the heroine becomes a serious, even profound, account of philosophical, social and ideological confrontations."[10] "In 'Malcolm's Katie' Crawford adapted to the setting of pioneer Canada the domestic idyll as she learned it from Tennyson. Striking and new, however, is Crawford's location of Max and Katie's conventional love story within a context of Native legends - Indian Summer and the battle of the North and South Winds."[9] This myth telling (however accurate it was as a portrayal of First Nations beliefs) is what many of its supporters see as giving the poem its power. For instance, writing about "Malcolm's Katie, critic Northrop Frye pronounced Crawford "the most remarkabe mythopoeic imagination in Canadian poetry":

- the "framework' of Isabella Crawford is that of an intelligent and industrious female songbird of the kind who filled so many anthologies in the last century. Yet the "South Wind" passage from Malcolm's Katie is only the most famous example of the most remarkable mythopoeic imagination in Canadian poetry. She puts her myth in an Indian form, which reminds us of the resemblance between white and Indian legendary heroes in the New World, between Paul Bunyan and Davy Crockett on the one hand and Glooscap on the other. The white myths are not necessarily imitated from the Indian ones, but they may have sprung from an unconscious feeling that the primitive myth expressed the imaginative impact of the country as more artificial literature could never do."[11]

Frye believed, and thought Crawford's "poetic sense" told her, "that the most obvious development in the romantic landscape is toward the mythological";[12] and he saw Crawford's attempt at an indigenous Canadian myth as the intellectual equivalent of the simultaneous pioneer exploration and settlement: "In the long mythopoeic passage from Isabella Crawford's Malcolm's Katie, beginning 'The South Wind laid his moccasins aside,' we see how the poet is, first, taming the landscape imaginatively, as settlement tames it physically, by animating the lifeless scene with humanized figures, and, second, integrating the literary tradition of the country by deliberately re-establishing the broken cultural link with Indian civilization."[13]

Hugh and Ion[]

Dorothy Livesay, researching Crawford's life for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography in 1977, discovered the manuscript of an uncompleted narrative poem in the Crawford fonds at Kingston, Ontario's Queen's University. Called Hugh and Ion, it deals with "Hugh and Ion, two friends who have fled the noxious city – probably contemporary Toronto – for purification in the primal wilderness [and] carry on a sustained dialogue, Hugh arguing for hope, light, and redemption and Ion pointing out despair, darkness, and intractable human perversity."[9]

Perhaps due to Crawford's Toronto experiences, this last poem marked a significant change in her views, showing the city as "a demonic, urban world of isolation and blindness which has wilfully cut itself off from the regenerative power of the wildernese. The confident innocence and romantic idealism, which account for much of the inner fire of Malcolm's Katie, have simply ceased to be operative.... Nowhere else in nineteenth-century Canadian literature, with the exception of Lampman's 'City [at] the End of Things," is there another example of the creative imagination being brought to bear, in so Blakean a manner, on the nascent social evils of the 'infant city.'"[10]

Critical introduction[]

by Pelham Edgar

Isabella Valancy Crawford used to print her verses in the corners of a Toronto evening paper, and she gathered them into a volume shortly before she died. Her talent might have asserted itself more victoriously with altered conditions, but under circumstances apparently the most adverse it refused to acknowledge defeat. She was poor, she was isolated from intellectual friendships, she was without recognition, and almost, one may say, without a country — for she left Ireland too young to have her memories rooted there, and had grown up in a land that had but feebly as yet developed its sense of nationhood. The only patriotic theme that inspired her was the Riel rebellion with its three dead heroes.

We can discover models, or at least sources of inspiration, for her younger contemporaries, for Mr. Roberts, Mr. Carman, and Archibald Lampman, but in Miss Crawford’s case it is not possible to name either her masters on her disciples in the craft of verse. The certain strokes of her art proclaim her of the great tradition, yet she is not the slave of any particular style. She is not a picker up of discarded phrases nor a renovator of outworn themes. Her charm is peculiarly her own, and had her opportunities for literary intercourse been greater her originality, the most precious of her gifts, might conceivably have been less.

One is sensible throughout her work of the springing vigour of her poetic fancy, and of the unfailing wealth of her imagery, which is “fresh and has the dew upon it.” Miss Wetherald, whose introduction to the Collected Poems deserves to be read, speaks of her power of striking out in direct and forcible phrases “the athletic imagery that crowded her brain,” and nothing indeed is more remarkable than the energetic way in which she conceives and executes her themes. What has been said of her may seem excessive praise, but if one accepts these superlatives as bearing upon the work of an avowedly minor poet they may be condoned.

One last thing to note in a young poetry so preponderatingly descriptive as ours is Valancy Crawford’s entire freedom from pedantry. She strikes no bargain with nature, but she looks outwards with unspoiled eyes and combines all her century’s passion for beauty with the simplicity of a less sophisticated time.[14]

Recognition[]

Entrance to Isabella Valancy Crawford Park, Toronto. Photo by Alan L. Brown, September 2006. Photo used with permission from the website Toronton's Historical Placques, www.torontohistory.org.

For a dozen years after Crawford's death, her grave was unmarked. A fundraising campaign was begun in 1899, and on November 2, 1900, a 6-foot Celtic Cross was raised above her grave, inscribed: "Isabella Valancy Crawford / Poet / By the Gift of God."[15]

Crawford was designated a Person of National Historic Significance in 1947.[16]

A small garden park in downtown Toronto, at Front and John Streets (near the CN Tower), has been named Isabella Valancy Crawford Park.[17]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Old Spookses' Pass, Malcolm's Katie and Other Poems. Toronto: privately published, 1884.

- Collected Poems, (edited by John Garvin). Toronto: William Briggs , 1905.

- Isabella Valancy Crawford (edited by Katherine Hale). Toronto: Ryerson,1923.

- Hugh and Ion (edited by Glenn Clever). Ottawa: Borealis Press, 1977. ISBN 9780919594777

- Malcolm's Katie: A love story (edited by D.M.R. Bentley). London, ON: Canadian Poetry Press, 1987. ISBN 0921243030

Novel[]

- Winona, or, The foster-sisters. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2006. ISBN 9781551117096

Short fiction[]

- Selected Stories (edited by Penny Petrone). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1975. ISBN 0776643355

- Fairy Tales (edited by Penny Petrone). Ottawa: Borealis P, 1977. ISBN 0919594530

- Collected Short Stories (edited by Len Early & Michel Peterman). London, ON: Canadian Poetry Press, 2006. ISBN 9780921243014

Except where noted, bibliographical information from Open Library.[18]

Poems by Isabella Valancy Crawford[]

The Canoe

- The Lily Bed

- "Love Me, Love My Dog"

- Malcolm's Katie: A Love Story

See also[]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wanda Campbell, "Isabella Valancy Crawford," Hidden Rooms: Early Canadian Women Poets (Toronto: Canadian Poetry Press, 2000), Canadian Poetry, UWO, Web, Mar. 31, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 D.M.R. Bentley, Introduction to Malcolm's Katie by Isabella Valancy Crawford, Canadian Poetry Press, UWO, Web, Mar. 30, 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Catherine Sheldrick Ross, "A New Biography of Isabella Valancy Crawford," Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews No. 38 (Spring/Summer 1996), UWO, Web, Mar. 31, 2011.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Dorothy Livesay, "Crawford, Isabella Valancy," Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, Web, Mar. 31, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 John Garvin, "Isabella Valancy Crawford," Canadian Poets (Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild, & Stewart, 1916), UPenn.edu, Web, Mar. 31, 2011

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 C.J. Taylor, "Crawford, Isabella Valancy," Canadian Encyclopedia (Edmonton: Hurtig, 1988), 531.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Crawford, Isabella Valancy," Encyclopedia of Canada (Toronto: University Associates, 1948), II, 145, Print.

- ↑ Elwood Jones, "A Great Poet We Hardly Knew," Peterborough Examiner, Article ID# 953499, Web, Apr. 13, 2011

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Catherine Ross, "Isabella Valancy Crawford Biography," Encyclopedia of Literature, 7642. JRank.org, Web, Mar. 31, 2011.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 James F. Johnson, "Malcolm's Kate, Hugh and Ion: Crawford's Changing Narrative Vision," Canadian Poetry: Studies/Documents/Reviews, No. 3 (Fall/Winter 1978), UWO, Web, Apr. 1, 2011

- ↑ Northrop Frye, "The Narrative Tradition in Canadian Poetry," The Bush Garden (Toronto: Anansi, 1971, 147-148).

- ↑ Northrop Frye, "Letters From Canada 1954," The Bush Garden, 34.

- ↑ Northrop Frye, "Preface to an Uncollected Anthology," The Bush Garden, 178.

- ↑ from Pelham Edgar, "Critical Introduction: Isabella Valancy Crawford (1850–1887)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Feb. 19, 2016.

- ↑ Elizabeth Galvin, Isabella Valancy Crawford, We Scarcely Knew Her (Hamilton: Dundurn, 1994), 78-79.

- ↑ "Persons of National Historic Significance," Wikipedia, Web, Apr. 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Isabella Valancy Crawford," Toronto's Historical Plaques, Web, Apr. 27, 2011.

- ↑ Search results: Isabella Valancy Crawford, OpenLibrary.org, Web, May 9, 2011.

External links[]

- Poems

- Crawford in A Victorian Anthology: "The Canoe," "The Axe"

- 2 poems by Crawford: "The Lily Bed," "O, Love builds on the azure sea"

- Crawford in The English Poets: An anthology: "La Blanchisseuse," "Said the Daisy," "The Rose," "O Love"

- Selected Poetry of Isabella Valancy Crawford - profile & 6 poems (The Camp of Souls, The Canoe, The Dark Stag, The Lily Bed, Malcolm's Katie: A Love Story, Old Spookses' Pass, Said the West Wind) at Representative Poetry Online

- Isabella Valancy Crawford in Canadian Poets - (Songs for the Soldiers, His Mother, His Wife and Baby, His Sweetheart, from 'Malcolm's Katie,' from 'The Helot,' The Mother's Soul)

- Isabella Valancy Crawford at PoemHunter (67 poems)

- Isabella Valancy Crawford at Poetry Nook (132 poems)

- Audio / video

- Isabella Valancy Crawford poems at YouTube

- Books

- Isabella Valancy Crawford at Canadian Poetry

- Works by Isabella Valancy Crawford at Project Gutenberg

- Isabella Valancy Crawford at Amazon.com

- About

- Isabella Valancy Crawford in the Canadian Encyclopedia

- Isabella Valancy Crawford in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- Winona; or, The foster-sisters at Broadview Press

- Isabella Valancy Crawford in the Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- "Malcolm's Katie: Love, Wealth, and Nation Building" by Robin Mathews

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

- This is a signed article by User:George Dance. It may be edited for spelling errors or typos, but not for substantive content except by its author. If you have created a user name and verified your identity, provided you have set forth your credentials on your user page, you can add comments to the bottom of this article as peer review.

|