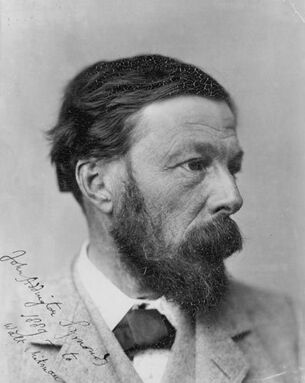

John Addington Symonds (1840-1893). Photo autographed to Walt Whitman, 1889. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

John Addington Symonds (5 October 1840 - 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic.

Life[]

Overview[]

Symonds, son of a physician in Bristol, was educated at Harrow and Oxford. His delicate health obliged him to live abroad. He published (1875-1886) History of the Italian Renaissance, and translated the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini. He also published some books of poetry, including Many Moods (1878) and Animi Figura (1882), and among his other publications were Introduction to the Study of Dante (1872), Studies of the Greek Poets (1873, 1876), Shakespeare's Predecessors in the English Drama (1884), and Lives of various poets, including Ben Jonson, Shelley, and Walt Whitman. He also made remarkable translations of the sonnets of Michelangelo and Campanella, and wrote upon philosophical subjects in various periodicals.[1]

Youth and education[]

Symonds was born at 7 Berkeley Square, Bristol, the only son of John Addington Symonds (1807–1871),[2] by his wife Harriet, eldest daughter of James Sykes of Leatherhead. He gave great intellectual promise, though associated with an incapacity for abstractions and a delight in the concrete, betokening the future historian and the artist which he became rather than the thinker which he would have liked to be.

At Harrow, whither he was sent in May 1854, he took little or no share in the school games, read with monotonous assiduity, but without the success commensurate with his ability, held aloof until his last year from boys of his own age, and became painfully shy.[3]

At Balliol, where he matriculated in 1858, his beginnings were not altogether promising; but soon, under the personal influence of Conington and Jowett, and of a host of friends whom his personality brought about him, he made rapid progress and gained brilliant distinction, obtaining a double 1st class in classics, the Newdigate, and an open fellowship at Magdalen College (27 Oct. 1862, after a failure at Queen's). Next spring he won a chancellor's prize for an English essay upon The Renaissance (Oxford, 1863, 8vo).[3]

The mental toil required by these achievements and still more mental restlessness and introspection impaired his health, developing the consumptive tendencies inherent in his mother's family – 6 months after his success at Magdalen he broke down altogether. Suffering from impaired sight and irritability of the brain, he sought refuge in Switzerland, and spent the winter in Italy.[3]

Marriage and early career[]

On 16 August 1864 he exchanged betrothal rings on the summit of Piz Languard with Janet Catherine North. They were married on 10 November at St. Clement's Church, Hastings. He settled in Albion Street, London, and afterwards at 47 Norfolk Square, where his eldest child, Janet, was born on 22 Octobr 1865.[3]

He began to study law, but soon found that this vocation suited neither his taste nor his health. The symptoms of pulmonary disease became more pronounced, and he was obliged to spend the greater part of several years on the continent, visiting the Riviera, Tuscany, Normandy (1867), and Corsica (1868). At length, in November 1868, he settled near his father at Victoria Square, Clifton, and devoted himself deliberately to a literary life.[3]

Symonds had already, in intervals of comparative health, contributed papers to the Cornhill Magazine and other periodicals; some of these, with other essays, were collected and published in 1874, under the title of Sketches in Italy and Greece (London, 8vo, 2nd edit. 1879). Further travel papers were collected in Sketches and Studies in Italy (London, 1879) and in Italian Byways (London, 1883, 8vo).[3]

His excellent Introduction to the Study of Dante (London, 1872, 8vo; 2nd edit. 1890, French version by Auger) was the result of lectures to a ladies' college at Clifton, and other lectures delivered at Clifton College produced his Studies of the Greek Poets in 2 series (1873 and 1876, both 3 editions). He edited the literary remains of his father, who died in 1871, and in the following year performed the same pious office for those of Conington, whom, after Jowett, he always considered his chief intellectual benefactor.[3]

In the spring of 1873 he visited Sicily and Greece. With returning health his literary ambition rekindled. The first volume of the history of the Renaissance in Italy, The Age of the Despots, appeared in 1875 (2nd edit. 1880). ‘It was,’ he says, 'entirely rewritten from lectures, and the defect of the method is clearly observable in its structure." The second and third volumes, The Revival of Learning (1877 and 1882) and The Fine Arts (1877 and 1882; Italian version by Santarelli, 1879), were composed in a different fashion, with great injury to the author's health, which compelled him to work principally abroad.[3]

He gave 3 lectures at the Royal Institution in February 1877 upon Florence and the Medici, and then, after a tour in Lombardy, when he began translating the sonnets of Michaelangelo and Campanella, he returned in June to Clifton; there he broke down with violent hæmorrhage from the lungs.[3]

At Davos[]

Symonds left England with the intention of proceeding to Egypt, but, stopping almost by accident at Davos Platz, derived so much benefit from the air during the winter 1877-1878 that he determined to make that then little known resort his home. Symonds contributed his experiences in an attractive article to the Fortnightly of July 1878. The essay powerfully stimulated the formation of English colonies not only at Davos but elsewhere in the Engadine, and it formed the nucleus of an interesting series of chapters on Alpine subjects, collected in Our Life in the Swiss Highlands (London, 1891, 8vo; 5 of the papers were by his 3rd daughter, Margaret).[3]

From 1878 Symonds spent the greater part of his life at Davos. On 20 September 1882 he settled in a house which he had built during the summer of 1881, and named "Am Hof." The change was in many ways highly advantageous to him,[3] especially as it gave him a more definite outlet for the charitable instincts which had always formed a leading element in his nature. Becoming intimately acquainted with the life of the small community around him, he took a leading part in its municipal business, and was able to render it service in many besides pecuniary ways, though here, too, he was most generous. [4]

Notwithstanding his habitual association with men of the highest culture, no trait in his character was more marked than his readiness to fraternise with peasants and artisans. He always made a point of providing relief for others, when possible, from his own earnings as a man of letters, leaving his fortune intact for his family.[4]

Literary commissions thronged upon him. He had already written the life of Shelley (1878) for the ‘English Men of Letters’ series, and in 1886 the life of Sir Philip Sidney was added. Both are fully up to the average level, but neither possesses the distinction with which some writers of abridged biographies have known how to invest their work. His Elizabethan studies bore fruit in Shakespeare's Predecessors (1884, new edit. 1900), in a Life of Ben Jonson (1886 and 1888), and in several minor studies for the ‘Mermaid Series’ (prefixed to Best Plays of Marlowe, Thomas Heywood, Webster, and Tourneur).[3]

The History of the Italian Renaissance was completed in 1886 by 4 further volumes, Italian Literature (London, 2 vols. 8vo, 1881) and The Catholic Reaction (2 vols. 1886). He computed that the work, which was abridged by Lieut.-Col. A. Pearson in 1893, and reissued in 7 volumes in 1897–8, occupied him the best part of 11 years.[4]

Meanwhile Symonds had followed up his translations of Michelangelo's and Campanella's sonnets (London, 1878, 8vo) with several volumes of verse, a form of composition for which, conscious probably of the mastery which he had actually acquired over poetic technique, he felt more predilection than his natural gifts entirely justified. Many Moods, a volume of poems, had been published in 1878. New and Old followed in 1880, Animi Figura (of special autobiographic interest) in 1882, and Vagabunduli Libellus in 1884.[4]

His excellent translations from the Latin songs of mediæval students appeared, with an elaborate preface upon Goliardic literature, under the title Wine, Women, and Song, with a dedication to Robert Louis Stevenson (London, 8vo, 1884 and 1889). He was next induced to undertake a prose translation of the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, published in 1887 (London, 2 vols. 8vo; also 1890 and 1893). It is a masterly performance; a version of The Autobiography of Count Carlo Gozzi (1890) is not inferior, and is accompanied by a valuable essay on the Italian impromptu comedy. He also contributed to the 9th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica articles on Italian history, the Renaissance, and Tasso.[4]

Last years[]

There are 2 men in Symonds whom it is hard to reconcile. His friends and intimates unanimously describe him as a man endowed with a zest and energy amounting to impetuosity, and their testimony is fully borne out by what is known of his taste for mountain-climbing and bodily exercise, his quick decision in trying circumstances, his ability in managing the affairs of the community to which he devoted himself, and the amount and facility of his literary productions. The evidence of his own memoirs and letters, on the other hand, would stamp him as a person given up to morbid introspection, and disabled by physical and spiritual maladies from accomplishing anything. The former is the juster view.[5]

In 1890 he published, under the title of Essays: Speculative and suggestive (London, 1890, 2 vols. 8vo, and 1893), a selection from the articles he had long been industriously contributing to reviews; 4 of these essays are on ‘Style,’ a subject to which they pay a somewhat ambiguous tribute; but 2 at least of the total number are excellent, one on The Philosophy of Evolution and the other a parallel between Elizabethan and Victorian Poetry. [4]

In 1892 Symonds issued the Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti (London, 2 vols. sm. 4to, 1892; 2nd edit. 1893). This was attempted on a scale involving an amount of toil in the collection of material from which, in his biographer's opinion, Symonds never recovered. The result was inadequate to the sacrifice; for although Symonds's work was meritorious, the new information he brought to light was not of paramount importance, and it was hardly worth his while to rewrite Michaelangelo's life unless he could treat it from a novel point of view.[4]

In 1893 he published another volume of detached criticisms, fancifully entitled In the Key of Blue. This book was remarkable, among other things, for an essay upon Edward Cracroft Lefroy, an unknown poet whose merits Symonds had detected, and whom he generously snatched from oblivion. In 1893 also, and upon the very day of Symonds's death, appeared Walt Whitman: A study (London, 8vo). It would hardly have been expected that such a rigid cultivator of poetic form as Symonds would find so much to admire in so amorphous a writer as Whitman, and in truth it was not so much the American's poetry that attracted him as identity of feeling on two cardinal points — democratic sympathy and the sentiment of comradeship.[4]

The intellectual and even physical activity of Symonds's life at Davos was cheered by the society of many other invalid refugees. Of these Robert Louis Stevenson was the most remarkable. "Beyond its splendid climate," says Stevenson in an unpublished letter, "Davos has but one advantage — the neighbourhood of J A. Symonds. I dare say you know his work, but the man is far more interesting." Stevenson celebrated Symonds as Opalstein (in "Talk and Talkers" in Memories and Portraits, 1887, p. 164). [4]

But serious lapses into ill-health and sad domestic bereavements caused Symonds much depression. His brother-in-law, Thomas Hill Green, who had married his sister Charlotte, died on 15 March 1882; his sister, Mary Isabella, wife of Sir Edward Strachey, on 5 October 1883; and his eldest daughter, Janet, in April 1887. [5]

During a visit to Rome in April 1893 a chill developed into pneumonia, and he expired on 19 April. He was interred in the protestant cemetery, close by Shelley; the Latin epitaph on his gravestone was written by Jowett.[5]

Writing[]

The posthumous works the publication of which Symonds desired, Blank Verse and Giovanni Boccaccio: Man and Author (London, 1894, 4to), did not add to his reputation. He bequeathed his papers to the care of Mr. Horatio F. Brown, the historian of Venice, who, by a skilful use of the autobiography (which Symonds had commenced in 1889), of diaries, and of letters contributed by friends, produced a model biography, executed on a large scale, but deeply interesting from beginning to end.[5]

Despite his tendency to abstract speculation, he had no capacity for it, although one of his essays, The Philosophy of Evolution, is a masterly presentation of the thoughts of others. When, however, he has to deal with something tangible, such as an historical incident or a work of art, whether literary or formative, he is invariably stimulating and suggestive, if not profound. Himself an Alexandrian, as one of his best critics has remarked, he is most successful in treating of authors whose beauties savor slightly of decadence, such as Theocritus, Ausonius, and Politian.[5]

His descriptive talent is especially remarkable, and his permanent reputation must mainly rest, apart from his translations, upon his History of the Italian Renaissance. Symonds's book, a labour of love, is not vivified by genius. It is a series of picturesque sketches rather than a continuous work, and the diverse aspects of the Renaissance, presented separately, are never sufficiently harmonised in the writer's mind. Detached portions are admirable, and if Symonds appears to have sometimes consulted his authors at second hand, it should be remembered that his access to libraries was greatly impeded by his captivity at Davos.[5]

As an original poet Symonds belongs to the class described by Johnson as extorting more praise than they are capable of affording pleasure. It is impossible not to admire the skill and science of his versification and the richness of his phraseology; but everything seems studied, nothing spontaneous; there is no sufficient glow of inspiration to fuse science and study into passion, and the perpetual glitter of fine words and ambitious thoughts becomes wearisome.[5]

He is much more successful as a translator, for here, the thoughts being furnished by others, there is no room for his characteristic defects, and his instinct for form and his copious vocabulary have full play. His versions of Michaelangelo's sonnets overcome difficulties which had baffled Wordsworth. Campanella, a still more crabbed original, is treated with even greater success, and difficulties of an opposite kind are no less triumphantly encountered in his renderings of the bird-like carols of Tuscany. His version of Benvenuto Cellini is likely to be permanently domesticated as an English book.[5]

Critical introduction[]

To read much of Symonds’s verse at a sitting is to be oppressed by a luxuriance that often runs to seed. His very facility, indeed, while it always gives his verse remarkable accomplishment, frequently leads him astray from the fine purposes of poetry, when he is content to describe the externalities of things, without exploring their sources. His work then, dazzling as it often is, becomes hard and slippery on the surface, and barren of the intimacy and precision which are the blood of poetry. In these moods—and they were not rare in his experience—he was the prey and not the master of words, and the seductiveness of a merely gorgeous verbal array confused his perception of the real nature of an image; as, for example —

Upon the pictured walls amid the blaze

Of carbuncle and turquoise, solid bosses

Of diamonds, pearl engirt, shot fiery rays:

Swan’s down beneath, with parrot plumage, glosses

Cedar-carved couches on the dais deep

In bloom of asphodel and meadow mosses.

Here languid men with pleasure tired may sleep:

Here revellers may banquet in the sheen

Of silver cressets: gourds and peaches heap

The citron tables; and a leafy screen,

This way and that with blossoms interlaced,

Winds through the hall in mazed alleys green.

This is striking virtuosity, but it is not the disciplined manner of poetry; it produces not an image in the mind, but a glittering confusion. It is, perhaps, in the shorter lyric, that searching test of a poet’s quality, that Symonds most suffered from his lack of strict poetic control; in this manner the large and impressive if florid gesture of his more elaborate work is of little use to him, and he finds himself untutored to stricter economy of the imagination, and the result is that his short lyrics, with very few exceptions, lack all the sudden and glowing presentation of words that means distinction. His really imposing accomplishment, too, was subject to startling lapses, such as

- Splits the throat

- Of maenad multitudes with shrill sharp shrieks,

and his literary scholarship should have saved him from such an indiscretion as —

- Pestilence-smitten multitudes, sere leaves

- Driven by the dull remorseless autumn breath.

And yet, in spite of his verbal ceremoniousness, and a habit of mind that too often led him from simple and stirring imaginative thought into every deft kind of fancy, he is justly allowed the honor of representation among his country’s poets. Not only had he great richness in description, which could be arresting when it was not unbridled, but there were moments when he wrote simply and with his eye on his object, as in Harvest, and the result gives him a place that we can only wish he had earned by a greater body of work of his best quality. There were other times when his very virtuosity reached such a pitch as to force something more than astonishment, as in Le Jeune Homme caressant sa Chimère, where he achieves a brilliance equalled by very few of his contemporaries.

Yet better, he could now and again subject himself to real emotional truth, and express it with sustained if unequal directness, as in Stella Maris. This sonnet sequence is, I think, his best achievement as a poet. The psychology may be a little uncertain, and the lover’s attitude is sometimes (e.g., Sonnets 52 and 53) intolerable, but the sequence as a whole does give real and often beautiful expression to a profound and passionate experience. There is here a spiritual intensity which Symonds generally missed, but by virtue of his having achieved it here and in one or two other places, he claims his place in the company of genuine poets.[6]

Homosexual writings[]

Front cover of the 1983 reprint edition

In 1873, Symonds wrote A Problem in Greek Ethics, a work of what could later be called "gay history," inspired by the poetry of Walt Whitman.[7] The work, "perhaps the most exhaustive eulogy of Greek love,"[8] remained unpublished for a decade, and then was printed at first only in a limited edition for private distribution.[9] Although the Oxford English Dictionary credits medical writer C.G. Chaddock for introducing "homosexual" into the English language in 1892, Symonds had already used the word in A Problem in Greek Ethics.[10] Symonds's approach throughout most of the essay is primarily philological. He treats "Greek love" as central to Greek "esthetic morality."[8] Aware of the taboo nature of his subject matter, Symonds referred obliquely to pederasty as "that unmentionable custom" in a letter to a prospective reader of the book,[11] but defined "Greek love" in the essay itself as "a passionate and enthusiastic attachment subsisting between man and youth, recognised by society and protected by opinion, which, though it was not free from sensuality, did not degenerate into mere licentiousness."[12]

Symonds studied classics under Benjamin Jowett at Balliol College, Oxford, and later worked with Jowett on an English translation of Plato's Symposium.[13] When Jowett was critical of Symonds' opinions on sexuality,[14] Symonds asserted that "Greek love is for modern studies of Plato no 'figure of speech' and no anachronism, but a present poignant reality."[15] Symonds struggled against the desexualization of "Platonic love," and sought to debunk the association of effeminacy with homosexuality by advocating a Spartan-inspired view of male love as contributing to military and political bonds.[16] When Symonds was falsely accused of corrupting choirboys, Jowett supported him, despite his own equivocal views of the relation of Hellenism to contemporary legal and social issues that affected homosexuals.[17]

Symonds also translated classical poetry on homoerotic themes, and wrote poems drawing on ancient Greek imagery and language such as Eudiades, which has been called "the most famous of his homoerotic poems": "The metaphors are Greek, the tone Arcadian, and the emotions a bit sentimental for present-day readers."[18]

One of the ways in which Symonds and Whitman expressed themselves in their correspondence on the subject of homosexuality was through references to ancient Greek culture, such as the intimate friendship between Callicrates, "the most beautiful man among the Spartans," and the soldier Aristodemus.[19]

While the taboos of Victorian England prevented Symonds from speaking openly about homosexuality, his works published for a general audience contained strong implications and some of the first direct references to male-male sexual love in English literature. For example, in "The Meeting of David and Jonathan", from 1878, Jonathan takes David "In his arms of strength / [and] in that kiss / Soul into soul was knit and bliss to bliss".

The same year, his translations of Michelangelo's sonnets to the painter's beloved Tommaso Cavalieri restore the male pronouns which had been made female by previous editors. By the end of his life, Symonds' homosexuality had become an open secret in Victorian literary and cultural circles.

In particular, Symonds' memoirs, written over a 4-year period, from 1889 to 1893, form the earliest known self-conscious homosexual autobiography. In addition to realizing his own homosexuality,

Over a century after Symonds' death his earliest work on homosexuality, Soldier Love and Related Matter, was finally published by Andrew Dakyns (grandson of Symonds' associate, Henry Graham Dakyns), Eastbourne, E. Sussex, England 2007. Soldier Love, or Soldatenliebe since it was limited to a German edition. Symonds' English text is lost. This translation and edition by Dakyns is the only version ever to appear in the author's own language.[20]

Recognition[]

Symonds won the Newdigate Prize in 1860 with a poem on The Escorial.[3]

Portraits of Symonds while at Harrow and Balliol, about 1870, in 1886, and 1891, are reproduced in the Life (1895). Another portrait is prefixed to Our Life in the Swiss Highlands, 1890.[3]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Escorial: A prize poem, recited in the theatre, Oxford, June 20, 1860. Oxford: T. & G. Shrimpton, 1860.

- Verses. Bristol, UK: privately printed by I. Arrowsmith, 1871.

- Many Moods: A volume of verse. London: Smith, Elder, 1878.

- New and Old: A volume of verse. London: Smith, Elder, 1880.

- Animi Figura. London: Smith, Elder, 1882.

Non-fiction[]

- The Renaissance: An essay read in the theatre, Oxford, June 17, 1863. Oxford, UK: Henry Hammans, 1863.

- Waste: A lecture delivered at the Bristol Institution for the Advancement of Science, Literature and the Arts. London: Bell & Daldy, 1863.

- An Introduction to the Study of Dante. London: Smith, Elder, 1872.

- Miscellanies. London: Macmillan, 1871.

- Studies of the Greek Poets. London: Smith, Elder, 1873.

- Honolulu, HI: University Press of the Pacific, 2002.

- Renaissance in Italy. (7 volumes), London: Smith, Elder, 1875–1886;

- Volume I: The age of the despots. London: Smith, Elder, 1875.

- Volume II: The revival of learning. London: Smith, Elder, 1877.

- Volume III: The fine arts. London: Smith, Elder, 1877

- Volume IV: Italian literature, Part I. London: Smith, Elder, 1881

- Volume V: Italian literature, Part II. London: Smith, Elder, 1881.

- Volumes VI-VII: The Catholic reaction, Parts Volumes I-II. London: Smith, Elder, 1886.

- Shelley. London: Macmillan, 1878; New York: Harper, 1879.

- Sketches and Studies in Italy and Greece. London: Smith, Elder, 1879.

- Second series. London: Smith, Elder, 1898.

- Third series. London: Smith, Elder, 1898.

- Shakspere's Predecessors in the English Drama. London: Smith, Elder, 1884.

- New Italian Sketches. Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1884.

- Sir Philip Sidney. London & New York: Macmillan, 1886; New York & London: Harper, 1886.

- Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Essays: Speculative and suggestive. (2 volumes), London: Chapman & Hall, 1890.

- Our Life in the Swiss Highlands. London & Edinburgh: A. & C. Black, 1892.

- A Problem in Modern Ethics: Being an inquiry into the phenomenon of sexual inversion, addressed especially to medical psychologists and jurists. London: 1896.

- In the Key of Blue, and other prose essays. London: Elkin Mathews & John Lane / New York: Macmillan, 1893.

- The Life of Michelangelo Buonarotti. London: J.C. Nimmo, 1893; New York: Modern Library, 1893.

- Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- A Short History of the Renaissance in Italy (edited by Alfred Pearson). London: Smith, Elder, 1893; New York: Holt, 1893.

- Walt Whitman: A Study. London: John C. Nimmo, 1893; London: Routledge, 1893.

- A Problem in Greek Ethics: Being an inquiry into the phenomenon of sexual inversion, addressed especially to medical psychologists and jurists. London: 1901.

- Last and first: Being two essays: The new spirit; and Arthur Hugh Clough. New York: Nicholas L. Brown, 1919.

- Memoirs (edited by Phyllis Grosskurth). London: Hutchinson, 1984; New York: Random House, 1984; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Soldier Love, and related matter (translated from German by Andrew Graham Dakyns). Eastbourne, UK: Andrew Dakyns, 2007.

Translated[]

- The Sonnets of Michael Angelo Buonarroti and Tommaso Campanella. Now for the first time translated into rhymed English. London: Smith Elder, 1878.

- Wine, Women, and Song; Mediaeval Latin students' songs now first translated into English verse, with an essay. London: Chatto & Windus, 1884.

- Benvenuto Cellin: The Life of Benvenuto Cellini: Newly translated into English. London: John C. Nimmo, 1888.

- Carlo Gozzi, The Memoirs of Count Carlo Gozzi. (2 volumes), London: John C. Nimmo, 1890. Volume I, Volume II

Edited[]

- John Conington, The Works of Virgil: Translated into English prose. London: George Bell, 1880; Boston, W. Small; Lee and Shepard / New York, C.T. Dillingham, 1880.

Letters and journals[]

- Letters and Papers (edited by Horatio F. Brown). London: John Murray, 1923.

- Letters (edited by Robert Peters & Herbert M. Schueller). Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1967-1969.

- Volume I: 1844-1868. 1967.

- Volume II: 1869-1884. 1968.

- Volume III: 1885-1893. 1969.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[21]

See also[]

John Addington Symonds - "The Vanishing Point"

Christmas Lullaby by John Addington Symonds

References[]

Garnett, Richard (1898) "Symonds, John Addington (1840-1893)" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 55 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 272-275. Wkisource, Web, Mar. 5, 2017.

- Phyllis Grosskurth, John Addington Symonds: A BNiography. 1964.

- The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds (edited by Phyllis Grosskurth). London: Hutchinson, 1984; New York: Random House, 1984.

Fonds[]

- John Addington Symonds papers, University of Bristol Library Special Collections

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Symonds, John Addington," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 370. Wikisource, Web, Mar. 10, 2018.

- ↑ Garnett, 272.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Garnett, 273.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Garnett, 274.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Garnett, 275.

- ↑ from John Drinkwater, "Critical Introduction: John Addington Symonds (1840–1893)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 28, 2016.

- ↑ Katz, Love Stories, p. 244. Katz notes that "Whitman's knowledge of and response to ancient Greek love is the subject for a major study" (p. 381, note 6).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 DeJean, "Sex and Philology," p. 139.

- ↑ Katz, Love Stories, p. 244. A Problem in Greek Ethics was later published without attribution in Havelock Ellis's Sexual Inversion (1897); see Eric O. Clarke, Virtuous Vice: Homoeroticism and the Public Sphere (Duke University Press, 2000), p. 144.

- ↑ DeJean, "Sex and Philology," p. 132, pointing to the phrase "homosexual relations" (here as it appears in the later 1908 edition).

- ↑ Katz, Love Stories, p. 262.

- ↑ As quoted by Pulham, Art and Transitional Object, p. 59, and Anne Hermann, Queering the Moderns: Poses/Portraits/Performances (St. Martin's Press, 2000), p. 148.

- ↑ Robert Aldrich, The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art, and Homosexual Fantasy (Routledge, 1993):78.

- ↑ Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality, 74, notes that Jowett, in his lectures and introductions, discussed love between men and women when Plato himself had been talking about the Greek love for boys.

- ↑ Aldrich, The Seduction of the Mediterranean, p. 78, citing a letter written by Symonds. Passage discussed also by Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality, p. 130 and Bart Schultz, Henry Sidgwick: An Intellectual Biography (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 381.

- ↑ Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality, p. 130.

- ↑ Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality, 88, 91.

- ↑ Aldrich, The Seduction of the Mediterranean, p. 78.

- ↑ Katz, Love Stories, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Soldier Love and Related Matter translated and edited by Andrew Dakyns. andrew.dakyns@balliol.oxon.org

- ↑ Search results = au:John Addington Symonds, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Nov. 27, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Venice" at Poetry Atlas

- John Addington Symonds at AllPoetry (2 poems)

- 3 poems by Symonds: "In February," "Harvest," "A Christmas Lullaby"

- Symonds in the Oxford Book of Victorian Verse: "Le Jeune Homme Caressant Sa Chimère," (Koina ta ton philon), "Farewell"

- Symonds in the Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse: "The Vanishing Point," "The Prism of Life," "Adventate Deo," "An Invocation"

- Symonds in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "An Episode," "Lux Est Umbra Dei," "The Nightingale," "The Fall of a Soul," "Farewell," "Il Fior Degli Eroici Furori," "Venice," "Thyself," "The Sonnet"

- Symonds in The English Poets: An anthology: "The Shepherd to the Evening Star," "Le Jeune Homme Caressant sa Chimère," "In the Inn at Berchtesgaden," Friends, "Harvest"

- Poetry at the John Addington Symonds pages (9 poems)

- John Addington Symonds at Poetry Nook (108 poems)

- Prose

- Audio / video

- John Addington Symonds poems at YouTube

- John Addington Symonds at LibriVox

- Books

- Works by John Addington Symonds at Project Gutenberg

- Symonds's translation of The Life of Benvenuto Cellini, Vol. 1, Posner LIbrary, Carnegie Mellon University Vol. 2, Carnegie Mellon University

- John Addington Symonds, Waste: a lecture delivered at the Bristol institution for the advancement of science, literature..., 1863

- John Addington Symonds, The Principles of Beauty, 1857

- John Addington Symonds at Amazon.com

- About

- John Addington Symonds in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Symonds, John Addington in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Biography, GLBTQ encyclopedia

- John Addington Symonds in the Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- 1998 Symonds International Symposium

- Robert Peters' MSS, Indiana University

- Psychoanalytic Quarterly

- The John Addington Symonds pages

- The John Addington Symonds Pages compiled by Rictor Norton

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Symonds, John Addington

|