John Keats (1795-1821). Portrait by William Hilton (1786-1839). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| John Keats | |

|---|---|

| Notable work(s) | 1819 odes |

John Keats (October 31, 1795 - February 23, 1821) was an English Romantic poet, generally considered to be among the greatest of English poets.

Life[]

John Keats documentary

Overview[]

Keats, was the son of the chief servant at an inn in London (who married his master's daughter, and died a man of some substance). He was sent to a school at Enfield, and having meanwhile become an orphan, was in 1810 apprenticed to a surgeon at Edmonton. In 1815 he went to London to walk the hospitals. He was not, however, at all enthusiastic in his profession, and having become acquainted with Leigh Hunt, Hazlitt, Shelley, and others, he gave himself more and more to literature. His earliest work — some sonnets — appeared in Hunt's Examiner, and his debut collection of Poems came out in 1817. This book, while containing much that gave little promise of what was to come, was not without touches of beauty and music, but it fell quite flat, finding few readers beyond his immediate circle. Endymion, begun during a visit to the Isle of Wight, appeared in 1818, and was savagely attacked in Blackwood and the Quarterly Review. These attacks, though naturally giving pain to the poet, were not, as was alleged at the time, the cause of his health breaking down, as he was possessed of considerable confidence in his own powers, and his claim to immortality as a poet. Symptoms of hereditary consumption, however, began to show themselves and, in the hope of restored health, he made a tour in the Lakes and Scotland, from which he returned to London none the better. The death soon after of his brother Thomas, whom he had helped to nurse, told upon his spirits, as did also his unrequited passion for Miss Fanny Brawne. In 1820 he published Lamia, and other poems, containing "Isabella," "Eve of St. Agnes," "Hyperion", and the odes to the "Nightingale" and "The Grecian Urn," all of which had been produced within a period of about 18 months. This book was warmly praised in the Edinburgh Review. His health had by this time completely given way, and he was likewise harassed by narrow means and hopeless love. He had, however, the consolation of possessing many warm friends, by some of whom, the Hunts and the Brawnes, he was tenderly nursed. At last in 1821 he set out, accompanied by his friend Severn, on that journey to Italy from which he never returned. After much suffering he died at Rome, and was buried in the Protestant cemetery there.[1]

The character of Keats was much misunderstood until the publication by R.M. Milnes of his Life and Letters, which gives an attractive picture of him. This, together with the accounts of other friends, represent him as "eager, enthusiastic, and sensitive, but humorous, reasonable, and free from vanity, affectionate, a good brother and friend, sweet-tempered, and helpful." In his political views he was liberal, in his religious, indefinite. Though in his life-time subjected to much harsh and unappreciative criticism, his place among English poets is now assured. His chief characteristics are intense, sensuous imagination, and love of beauty, rich and picturesque descriptive power, and exquisitely melodious versification.[1]

Along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Keats was a key figure in the second generation of the Romantic movement, despite the fact that his work had been in publication for only 4 years before his death.[2] After his death, his reputation grew to the extent that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He has had a significant influence on a diverse range of later poets and writers: Jorge Luis Borges, for instance, stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[3] Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and analyzed in English literature.

Youth and education[]

Keats was born on 31 October 1795 to Francis (Jennings) and Thomas Keats, the eldest of their 4 surviving children: John, George [1797-1841], Thomas [1799-1818), and Frances Mary or "Fanny" [1803-89]; another son died in infancy}. John was born in central London, although there is no clear evidence of the exact location.[4] His father worked as a hostler,[5] at the stables attached to the Swan and Hoop inn, an establishment Thomas later managed and where the growing family would live for some years. The Keats at the Globe pub now occupies the site, a few yards from modern day Moorgate station.

Keats was baptised at St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate and sent to a local dame school as an infant. In the summer of 1803, unable to attend Eton or Harrow due to the expense,[6][7] he was sent to board at John Clarke's school in Enfield, close to his grandparents' house. The small school had a liberal and progressive outlook, with a curriculum ahead of its time, a place altogether more modern than the larger, more prestigious schools. [8] In the family atmosphere at Clarke's, Keats developed an interest in classics and history which would stay with him throughout his short life. The headmaster's son, Charles Cowden Clarke, would become an important influence, mentor and friend, introducing Keats to Renaissance literature including Tasso, Spenser. and Chapman's translations.

The instability of Keats's childhood gave rise to a volatile character "always in extremes", given to indolence and fighting. However at 13 he began focusing his energy towards reading and study, winning an academic prize in midsummer 1809. [8]

In April 1804, when Keats was 8, his father was killed, fracturing his skull after falling from his horse on a return visit to the school. Thomas died intestate. Frances remarried 2 months later, but left her new husband soon afterwards, her 4 children going to live with the children's grandmother, Alice Jennings, in the village of Edmonton.[9]

In March 1810, when Keats was 14, his mother died of tuberculosis leaving the children in the custody of their grandmother who appointed two guardians to take care of the children. That autumn, Keats was removed from Clarke's school to apprentice with Thomas Hammond, a surgeon and apothecary, lodging in the attic above the surgery until 1813. Cowden Clarke, who remained a close friend of Keats, described this as "the most placid time in Keats's life".[10]

Early career[]

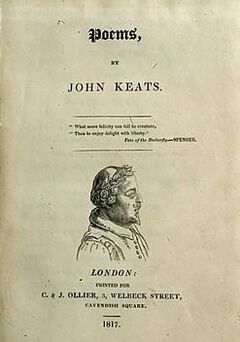

Title page of Keats' Poems, 1817. Courtesy Duke University.

Having finished his apprenticeship with Hammond, Keats registered as a medical student at Guy's Hospital (now part of King's College London) and began there in October 1815. Within a month of starting, he was accepted for a dressership position within the hospital, the equivalent of a junior house surgeon. It was a significant promotion marking a distinct talent for medicine, the role coming with increased responsibility and workload. His long and expensive medical training with Hammond and at Guys gave his family to assume this would be his lifelong career, assuring financial security. [8]

Keats's earliest surviving poem, An Imitation of Spenser, was written in 1814, when Keats was 19. His medical career took up increasing amounts of his writing time and exacerbated his ambivalence to anything other than poetry.[8] [11] Strongly drawn by ambition, inspired by fellow poets such as Leigh Hunt and Byron, and beleaguered by family financial crises that continued to the end of his life, he suffered periods of depression. His brother George wrote that John "feared that he should never be a poet, & if he was not he would destroy himself".[12]

In 1816, Keats received his apothecary's licence but before the end of the year he announced to his guardian that he had resolved to be a poet, not a surgeon. Though he continued his work and training at Guy's, Keats was devoting increasing time to the study of literature. In May 1816, Leigh Hunt agreed to publish the sonnet "O Solitude" in his magazine The Examiner, a leading liberal magazine of the day.[13] It is the first appearance of Keats's poems in print and Cowden Clarke refers to it as his friend's red letter day,[14] first proof that Keats's ambitions were valid. In the summer of that year he went down to the coastal town of Margate with Clarke to write. There he began Calidore and initiated the era of his great letter writing.

In October, Clarke introduced Keats to Hunt, a close friend of Byron and Shelley. 5 months later Poems, the 1st volume of Keats verse, was published, which included "I stood tiptoe" and "Sleep and Poetry".[13] It was a critical failure, arousing no interest, his publishers feeling ashamed of the book. [8] Still, Hunt went on to publish the essay "Three Young Poets" (Shelley, Keats and Reynolds), along with the sonnet "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer," promising great things to come.[15] He introduced Keats to many prominent men in his circle, including the editor of The Times, Thomas Barnes, writer Charles Lamb, conductor Vincent Novello and poet John Hamilton Reynolds, who would become a close friend.[16] It was a decisive turning point for Keats, establishing him in the public eye as a figure in what Hunt termed "a new school of poetry."[17] At this time Keats wrote to his friend Bailey "I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the Heart's affections and the truth of the imagination. What imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth".[2][18] This would eventually transmute into the concluding lines of "Ode on a Grecian Urn."

In bad health and unhappy with living in London, Keats moved with his brothers into rooms at 1 Well Walk in April 1817. Both John and George nursed their brother Tom, who was suffering from tuberculosis. The house in Hampstead was close to Hunt and others from his circle, as well as the senior poet Coleridge who at the time lived in Highgate.[19] In June 1818, Keats began a walking journey around Scotland, Ireland and the Lake District with his friend Charles Armitage Brown.

George and his wife Georgina accompanied them as far as Lancaster and then headed to Liverpool, from where the couple would emigrate to America. They lived in Ohio and Louisville, Kentucky until 1841 when George's investments went bad. Like both of Keats's brothers, they died penniless and racked by tuberculosis. There would be no effective treatment for the disease until 1921.[20][21]

In July, while on the Isle of Mull for the walking tour, Keats caught a bad cold and "was too thin and fevered to proceed on the journey".[22] On his return south, Keats continued to nurse Tom, exposing himself to the highly infectious disease. Some biographers suggest that this is when tuberculosis, his "family disease", takes hold.[23][24][25] Tom Keats died on 1 December 1818.

Wentworth Place[]

Wentworth Place, now the Keats House Museum. Photo by ceridwen. Courtesy Geograph.org.

John Keats moved to the newly built Wentworth Place, owned by his friend Charles Armitage Brown, also on the edge of Hampstead Heath, a 10-minute walk south of his old home in Well Walk. This winter of 1818-19, though troubled, marks the beginning of Keats's annus mirabilis in which he wrote his most mature work.[2]

He had been greatly inspired by a series of recent lectures by Hazlitt on English poets and poetic identity and met with Wordsworth.[26] In December he attended Haydon's 'immortal dinner', along with Wordsworth and Charles Lamb. [27]

Keats composed 5 of his 6 great odes there in April and May and, although it is debated in which order they were written, "Ode to Psyche" starts the series. According to Brown, "Ode to a Nightingale" was composed under a mulberry tree in the garden.[28][29] Brown wrote, "In the spring of 1819 a nightingale had built her nest near my house. Keats felt a tranquil and continual joy in her song; and one morning he took his chair from the breakfast-table to the grass-plot under a plum-tree, where he sat for two or three hours. When he came into the house, I perceived he had some scraps of paper in his hand, and these he was quietly thrusting behind the books. On inquiry, I found those scraps, four or five in number, contained his poetic feelings on the song of our nightingale."[30] Dilke, co-owner of the house, strenuously denied the story, printed in Milnes' 1848 biography of Keats, dismissing it as pure delusion.

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

- Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,-

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

May 1819

The new and progressive firm Taylor & Hessey published Endymion, dedicated to Thomas Chatterton. It was damned by the critics, giving rise to Byron's quip that Keats was ultimately "snuffed out by an article". A particularly harsh review by John Wilson Croker appeared in the April 1818 edition of The Quarterly Review "It is not, we say, that the author has not powers of language, rays of fancy, and gleams of genius - he has all these; but he is unhappily a disciple of the new school of what has been somewhere called 'Cockney Poetry'; which may be defined to consist of the most incongruous ideas in the most uncouth language.... There is hardly a complete couplet enclosing a complete idea in the whole book. He wanders from one subject to another, from the association, not of ideas, but of sounds."[31]

John Gibson Lockhart wrote in Blackwood's Magazine: "To witness the disease of any human understanding, however feeble, is distressing; but the spectacle of an able mind reduced to a state of insanity is, of course, ten times more afflicting. It is with such sorrow as this that we have contemplated the case of Mr John Keats. [...] He was bound apprentice some years ago to a worthy apothecary in town. But all has been undone by a sudden attack of the malady [...] For some time we were in hopes that he might get off with a violent fit or two; but of late the symptoms are terrible. The phrenzy of the "Poems" was bad enough in its way; but it did not alarm us half so seriously as the calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy of Endymion. [...] It is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the [apothecary] shop Mr John, back to 'plasters, pills, and ointment boxes'.[32] It was Lockhart at Blackwoods who had coined the defamatory term "the Cockney School" for Hunt and his circle, including William Hazlitt and, squarely, Keats. The dismissal was as much political as literary - aimed at upstart young writers deemed uncouth for their lack of education, non-formal rhyming and "low diction". They had not attended Eton, Harrow or Oxbridge colleges and they were not from the upper classes.

In 1819, Keats wrote "The Eve of St. Agnes", "La Belle Dame sans Merci", "Hyperion", "Lamia" and Otho (critically damned and not dramatised until 1950). The poems "Fancy" and "Bards of passion and of mirth" were inspired by the gardens. In September, very short of money, he approached his publishers with a new book of poems. They were unimpressed with the collection, finding the presented versions of "Lamia" confusing, and describing "St Agnes" as having a "sense of pettish disgust" and "a 'Don Juan' style of mingling up sentiment and sneering" concluding it was "a poem unfit for ladies".[33] The final volume Keats lived to see, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, was eventually published in July 1820. It received greater acclaim than had Endymion or Poems, finding favourable notices in both The Examiner and Edinburgh Review.

Wentworth Place now houses the Keats House museum.[34]

Ambrotype of Fanny Brawne taken circa 1850 (photograph on glass)

Fanny and Isabella[]

- Main article: Fanny Brawne

Letters and poem drafts suggest that Keats first met Frances (Fanny) Brawne between September and November 1818.[35] It is likely that the 18-year-old Brawne was visiting the Dilke family at Wentworth Place, before she lived there. Like Keats, Brawne was a Londoner, born in the hamlet of West End near Hampstead on 9 August 1800. Her grandfather had kept a London inn, as Keats's father had done, and had also lost several members of her family to tuberculosis. She shared her first name with both Keats's sister and mother. Brawne had a talent for dress-making and languages . She describes herself as having "a natural theatrical bent".[36] During November 1818 an intimacy sprang up between Keats and Brawne but was very much shadowed by the impending death of Tom Keats, whom John was nursing.[37]

That year, he met the beautiful, talented and witty Isabella Jones, for whom he also felt a conflicted passion. He had met her in Hastings while on holiday in June. He "frequented her rooms" in the winter of 1818-1819, and says in his letters to George that he "warmed with her" and "kissed her".[38] It is unclear how close they ultimately became and biographers debate how influential she was to Keats's writing. Gittings maintained that The Eve of St. Agnes and The Eve of St Mark were suggested by her, that the lyric Hush, Hush! ["o sweet Isabel"] was about her and the first version of Bright Star might well have been for her.[39][40]

On 3 April 1819, Brawne and her widowed mother moved into the other half of Dilke's Wentworth Place and Keats and Brawne were able to see each other every day. Keats began to lend Brawne books, such as Dante's Inferno, and they would read together. He gave her the love sonnet "Bright Star" (perhaps revised for her) as a declaration. It was a work in progress and he continued to work on the poem until the last months of his life and the poem came to be associated with their relationship. "All his desires were concentrated on Fanny".[41] From this point we have no documented mention of Isabella Jones again.[41] Sometime before the end of June, he arrived at some sort of understanding with Brawne, far from a formal engagement as he still had too little to offer, with no prospects and financial stricture.[42]

Keats endured great conflict knowing his expectations as a struggling poet in increasingly hard straits would preclude marriage to Brawne. Their love remained unconsummated; jealousy for his 'star' began to gnaw at him. Darkness, disease and depression were around him, and are reflected in poems of the time such as The Eve of St. Agnes and La Belle Dame sans Merci where love and death both stalk. "I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks;" he wrote to her, "...your loveliness, and the hour of my death".[42] Keats writes to Brawne in one of his many notes and letters: "My love has made me selfish. I cannot exist without you - I am forgetful of every thing but seeing you again - my Life seems to stop there - I see no further. You have absorb'd me. I have a sensation at the present moment as though I was dissolving - I should be exquisitely miserable without the hope of soon seeing you. [...] I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion - I have shudder'd at it - I shudder no more - I could be martyr'd for my Religion - Love is my religion - I could die for that - I could die for you." (Letter, 13 October 1819).

Tuberculosis took hold and he was advised to move to a warmer country by his doctors. In September 1820 Keats left for Rome and they both knew it was very likely they would never see each other again. He died there five months later. None of Brawne's letters to Keats survive, though we have his own letters. As the poet had requested, Brawne's were destroyed upon his death. She stayed in mourning for Keats for six years. In 1833, more than 12 years after his death, she married and went on to have three children, outliving Keats by more than 40 years.[34][43] The 2009 film Bright Star, written and directed by Jane Campion, focuses on Keats' relationship with Fanny Brawne.

Death[]

Graves of John Keats and Joseph Severn in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome. Photo by Howard Hudson. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

During 1820, Keats displayed increasingly serious symptoms of tuberculosis, to the extent that he suffered two lung haemorrhages in the first few days of February.[44][45] He lost large amounts of blood and was bled further by the attending physician. Hunt nursed him in London for much of the summer. At the suggestion of his doctors, he agreed to move to Italy with his friend Joseph Severn.

On 13 September, they left for Gravesend and 4 days later boarded the sailing brig Maria Crowther. Keats wrote his final revisions of "Bright Star" aboard the ship. The journey was a minor catastrophe: storms broke out followed by a dead calm that slowed the ship's progress. When it finally docked in Naples, the ship was held in quarantine for 10 days because of a suspected outbreak of cholera in Britain. Keats reached Rome on November 14, by which time all hope of a warmer climate had evaporated.[46]

On arrival in Italy, he moved into a villa on the Spanish Steps in Rome, today the Keats-Shelley Memorial House museum. Despite care from Severn and Dr. James Clark, his health rapidly deteriorated. The medical attention Keats received may have hastened his death.[47] In November 1820, Clark declared that the source of his illness was "mental exertion" and that the source was largely situated in his stomach. Clark eventually diagnosed consumption (tuberculosis) and placed Keats on a starvation diet of an anchovy and a piece of bread a day intended to reduce the blood flow to his stomach. He also bled the poet; a standard treatment of the day, but likely a significant contributor to Keats's weakness.[48]

Keats's friend Brown writes: "They could have used opium in small doses, and Keats had asked Severn to buy a bottle of opium when they were setting off on their voyage. What Severn didn't realise was that Keats saw it as a possible resource if he wanted to commit suicide. He tried to get the bottle from Severn on the voyage but Severn wouldn't let him have it. Then in Rome he tried again. [...] Severn was in such a quandary he didn't know what to do, so in the end he went to the doctor who took it away. As a result Keats went through dreadful agonies with nothing to ease the pain at all." [48]

Keats was furious with both Severn and Clarke when they refused laudanum (opium). He repeatedly demanded "how long is this posthumous existence of mine to go on?". Severn writes, "Keats raves till I am in a complete tremble for him," [48] continuing, "about four, the approaches of death came on. [Keats said] 'Severn - I - lift me up - I am dying - I shall die easy; don't be frightened - be firm, and thank God it has come.' I lifted him up in my arms. The phlegm seem'd boiling in his throat, and increased until eleven, when he gradually sank into death, so quiet, that I still thought he slept."[49]

Keats's grave in Rome

He died on 23 February 1821 and was buried in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome. His last request was to be placed under an unnamed tombstone which contained only the words (in pentameter), "Here lies one whose name was writ in water." Severn and Brown erected the stone, which under a relief of a lyre with broken strings, contains the epitaph: This Grave / contains all that was Mortal / of a / Young English Poet / Who / on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart / at the Malicious Power of his Enemies / Desired / these Words to be / engraven on his Tomb Stone: / Here lies One / Whose Name was writ in Water. 24 February 1821"

There is a discrepancy of a day between the official date of death and the grave marking. Severn and Brown had added their lines to the stone in protest at the critical reception of Keats's work. Hunt blamed his death on the scathing attack of "Endymion" by the Quarterly Review. Seven weeks after the funeral, Shelley memorialised Keats in his poem Adonais.[50] Clark saw to the planting of daisies on the grave, saying that Keats would have wished it. For public health reasons, the Italian health authorities burned the furniture in Keats's room, scraped the walls, made new windows, doors and flooring.[51][52] The ashes of Shelley (d. 8 July 1822), one of Keats's most fervent champions, are also buried there along with Severn (d. 3 August 1879) who nursed Keats to the end. Describing the vista of the site today, Marsh wrote, "In the old part of the graveyard, barely a field when Keats was buried here, there are now umbrella pines, myrtle shrubs, roses, and carpets of wild violets". [46]

Writing[]

How to Read the Poetry of John Keats

The poetry of Keats is characterized by "vivid imagery, great sensuous appeal, and an attempt to express a philosophy through classical legend."[53]

Poetry[]

Relief on wall near his grave in Rome

When Keats died at the age of 25, he had been seriously writing poetry for only about 6 years, from 1814 until the summer of 1820, and publishing for 4. It is believed that, in his lifetime, sales of Keats's 3 volumes of poetry amounted to only 200 copies.[54]

His earliest published poem, the sonnet O Solitude appeared in the Examiner in May 1816, while his collection Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes and other poems was published in July 1820 before his final voyage to Rome. The compression of his poetic apprenticeship and maturity into so short a time is a remarkable aspect of Keats's work.[2] Although he was prolific during his short writing life, and is now one of the most studied and admired of British poets, his reputation rests on a small body of work, centred on the Odes,[55] and it was only in the creative outpouring in the last years of his short life that he was able to express in craft the inner intensity for which he has been lauded since his death.[56] Keats was convinced that he had made no mark in his lifetime. Knowing he was dying, he wrote to Fanny Brawne in February 1820, "I have left no immortal work behind me - nothing to make my friends proud of my memory - but I have lov'd the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time I would have made myself remember'd."

Keats's skills were acknowledged in his lifetime by several influential allies such as Shelley and Hunt.[54] His admirers praised him for thinking "on his pulses", for having developed a style which was more heavily loaded with sensualities, more gorgeous in its effects, more voluptuously alive than any poet who had come before him: 'loading every rift with ore'.[57] Shelley had corresponded often with Keats when he was ill in Rome and loudly declared that Keats's death had been brought on by bad reviews in the Quarterly Review. Seven weeks after the funeral he wrote "Adonais", a despairing elegy,[58] calling Keats's early death a personal and public tragedy:

The loveliest and the last,

The bloom, whose petals nipped before they blew

Died on the promise of the fruit.[59][60]

Shelley's admiration for Keats's work was not shared by their contemporary Byron. In September 1820 Byron wrote from Ravenna to his publisher, John Murray, thanking him for sending him some recently-published books, but complaining about most of them, including "Johnny Keats's p*ss a bed poetry."[61]

Although Keats wrote that "if poetry comes not as naturally as the Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all", poetry did not come easy to Keats, his work the fruit of a deliberate and prolonged self-education in classical literature. He may have possessed an innate poetic sensibility, but his early works were clearly of a poet learning his craft; his first attempts at verse were often vague, languorously narcotic and lacking a clear eye.[56] His poetic sense was based on the conventional tastes of his friend Charles Cowden Clarke, who first introduced him to the classics, and came also from the predilections of Hunt's Examiner, which Keats had read from a boy.[62] Hunt scorned the Augustan or 'French' school, dominated by Pope, and attacked the earlier Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge, now in their forties, as unsophisticated, obscure and crude writers. Indeed, during Keats's few years as a publishing poet, the reputation of older Romantic school was at its lowest ebb. Keats came to echo these sentiments in his work, identifying himself with a 'new school' for a time, somewhat alienating him from Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron and providing the basis for the scathing attacks from Blackwoods and The Quarterly.[62]

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eaves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.

September 1819

By the time of his death, Keats had therefore been associated with the taints of both old and new schools: the obscurity of the first wave Romantics and the uneducated affectation of Hunt's "Cockney School". Keats's reputation after death mixed the reviewers' caricature of the simplistic bumbler with the image of the hyper-sensitive genius killed by high feeling, which Shelley later portrayed. [62]

Letters[]

Keats' letters were first published in 1848 and 1878. During the 19th century, critics had deemed them unworthy of attention, even detracting from the body of poetic works.[63] However during the 20th century they became almost as admired and studied as his poetry,[27] and rank highly in the history of all English literary correspondence.[64] T.S. Eliot described them as "certainly the most notable and most important ever written by any English poet."[27][65] Keats spent a great swath of his time as a poet considering poetry itself, its constructs and impacts, a deep interest unusual amongst his milieu, who were more easily distracted by metaphysics or politics, fashions or science. As Eliot wrote of Keats's conclusions: "There is hardly one statement of Keats' about poetry which [...] will not be found to be true, and what is more, true for greater and more mature poetry than anything Keats ever wrote."[63]

Keats and his friends, poets, critics, novelists, and editors were prolific daily letter writers and Keats' ideas are bound up in the ordinary, his day-to-day missives sharing news, parody and social commentary. Born of an "unself-conscious stream of consciousness," they are impulsive, full of awareness of his own nature and his weak spots.[63]When his brother George went to America, Keats wrote to him in great detail, the body of letters becoming "the real diary" and self-revelation of Keats's life, as well as containing an exposition of his philosophy, and the first drafts of poems containing some of Keats's finest writing and thought.[66] Gittings describes them as akin to a "spiritual journal" not written for a specific other, so much as for synthesis.[63]

Keats also reflects on the background and composition of his poetry, and specific letters often coincide with or anticipate the poems they describe.[63] Writing to his brother George in spring 1819, Keats explored the idea of the world as "the vale of Soul-making", anticipating the great odes that he would write some months later.[63][67] In the letters, Keats coined ideas such as the Mansion of Many Apartments and the Chameleon Poet, concepts that came to gain common currency and capture the public imagination, despite only making single appearances as phrases in his correspondence.[68] The poetical character, Keats argues "has no self - it is every thing and nothing - It has no character - it enjoys light and shade; [...] What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion [chameleon] Poet. It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity - he is continually in for - and filling some other Body - The Sun, the Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute - the poet has none; no identity - he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God's Creatures." He outlines Negative capability as the poetic state in which we are "capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason. [...Being] content with half knowledge" where one trusts in the heart's perceptions.[69] He writes later "I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the Heart's affections and the truth of Imagination - What the imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth - whether it existed before or not - for I have the same Idea of all our Passions as of Love they are all in their sublime, creative of essential Beauty"[70] again and again turning to the question of what it means to be a poet.[26] "My Imagination is a Monastry and I am its Monk", Keats notes to Shelley. In September 1819, Keats wrote to Reynolds "How beautiful the season is now - How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it ... I never lik'd the stubbled fields as much as now- Aye, better than the chilly green of spring. Somehow the stubble plain looks warm - in the same way as some pictures look warm - this struck me so much in my Sunday's walk that I composed upon it".[71] The final stanza of his last great ode: "To Autumn" runs:

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,-

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Long after his death, To Autumn would go on to become one of the most highly regarded poems in the English language: "Each generation has found it one of the most nearly perfect poems in English."[72] The 1888 Encyclopaedia Britannica declared that, "Of these [odes] perhaps the two nearest to absolute perfection, to the triumphant achievement and accomplishment of the very utmost beauty possible to human words, may be that of to Autumn and that on a Grecian Urn."[73]

There are areas of his life and daily routine that Keats does not describe. He mentions little about his childhood, his parents or his financial straits and is seemingly embarrassed to discuss them. In his last year, as his health gave way, his concerns often gave way to despair and morbid obsessions. The publications of letters to Fanny Brawne in 1870 focused on this period and emphasised this tragic aspect, giving rise to widespread criticism at the time.[63]

Recognition[]

Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The Victorian sense of poetry as the work of indulgence and luxuriant fancy, offered a schema into which Keats was posthumously fitted. Marked as the standard bearer of sensory writing, his reputation grew steadily and remarkably.[62] This is attributed to several factors. Keats's work had the full support of the influential Cambridge Apostles, (founded 1820). The society included a young Tennyson,[74] later a hugely popular Poet Laureate, who came to regard Keats as the greatest poet of the 19th century.[27]

English poet Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, in 1848 wrote the first biography of Keats, which (says the Dictionary of Literary Biography) "played a major role in rescuing John Keats's reputation from oblivion."[75]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Millais and Rossetti, took Keats as a key muse, painting scenes from his poems including "The Eve of St. Agnes", "Isabella" and "La Belle Dame sans Merci" -- lush, arresting and popular images which remain closely associated with Keats's work.[62]

In 1882, Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica that "the Ode to a Nightingale, [is] one of the final masterpieces of human work in all time and for all ages".[76]

15 of his poems ("Song of the Indian Maid," "Ode to a Nightingale," "Ode on a Grecian Urn," "Ode to Psyche," "To Autumn," "Ode on Melancholy," "Fragment of an Ode to Maia," "Bards of Passion and of Mirth," "Fancy," "Stanzas," "Las Belle Dame sans Merci," "On first looking into Chapman's Homer," "When I have Fears that I may cease to be," "To Sleep," and "Last Sonnet") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900.[77]

In the 20th century Keats remained the muse of poets such as Wilfred Owen (who kept his death date as a day of mourning), Yeats, and Eliot. [62] Helen Vendler stated the odes "are a group of works in which the English language finds ultimate embodiment".[78] Jonathan Bate declared of To Autumn: "Each generation has found it one of the most nearly perfect poems in English"[79] and M.R. Ridley claimed the ode "is the most serenely flawless poem in our language."[80]

A memorial to Keats and Shelley was unveiled in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, by then-Poet Laureate John Masefield in 1954.[81]

The largest collection of the letters, manuscripts, and other papers of Keats is in the Houghton Library at Harvard University. Other collections of material are archived at the British Library, Keats House, Hampstead, the Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome and the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. Since 1998 the British Keats-Shelley Memorial Association have annually awarded a poetry prize.[82]

Biographical controversy[]

Nobody who had known Keats ever wrote a full biography of Keats's life.[83] Shortly after Keats's death in 1821, his publishers Taylor & Hessey announced they would speedily publish The Memoirs and Remains of John Keats but his friends refused to co-operate with the venture and the project was abandoned. There were "biographical jottings of varying natures and values"[83] about the poet who had become a figure within artistic circles - including prolific notes, chapters and letters from his many artist and writer friends. These, however, often give contradictory or heavily biased accounts of events and were subject to quarrels and rifts.[83]

His friends Brown, Severn, Dilke, Shelley and Hunt, his guardian Richard Abbey, his publisher Taylor, Fanny Brawne and many others issued posthumous commentary on Keats's life. These early writings coloured all subsequent biography and have become embedded into a body of Keats legend.[84] Shelley promoted Keats as someone whose achievement could not be separated from agony, who was 'spiritualised' by his decline, and simply too fine-tuned to endure the buffetings of the world. This is the consumptive, suffering image popularly held today.[85]

After much dithering, the first official biography was published in 1848 by Richard Monckton Milnes (1809-“1885). Landmark Keats biographers since, include Sidney Colvin (1845-1927), Robert Gittings (1911-1992), Walter Jackson Bate (1918-1999) and Andrew Motion (b. 1952).

Keats is also the subject of a 1934 biography by Canadian poet Raymond Knister.

Publications[]

- Main article: John Keats bibliography

Poetry[]

- Poems. London: C. & J. Ollier, 1817.

- Endymion: A Poetic Romance. London:Taylor & Hessey, 1818.

- Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and other poems. London: Taylor & Hessey, 1820.

Collected editions[]

- The Poetical Works of Coleridge, Shelley, and Keats. Paris: A. & W. Galignani, 1829; Philadelphia: Stereotyped by J. Howe, 1831.

- The Poetical Works of John Keats. London: William Smith (Smith's Standard Library), 1840.

- The Poetical Works of John Keats. New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1846.

- Life, Letters, and Literary Remains (edited by Richard Monckton Milnes, Lord Houghton). London: Moxon, 1848; Philadelphia, Putnam, 1848.

- Poetical Works (edited by William Arnold). London: Kegan Paul Trench, 1884.[86]

- Poetical Works (with notes by Franis T. Palgrave). London: Macmillan, 1884.[87]

- Complete Poetical Works and Letters (edited by H. Buxton Foreman). New York: Thomas Crowell, 1895.

- Poems by John Keats (edited by Arlo Bates). Boston & London: Ginn, 1896.[88]

- Poetical Works (edited by H.W. Garrod). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1939.[89]

- The Poems of John Keats (edited by Jack Stillinger). Cambridge, MA.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978.

Letters[]

- Letters of John Keats to Fanny Brawne: Written in the Years of MDCCCXIX and MDCCCXX. New York: George Broughton and Barclay Dunham, 1901.[90]

- Letters of John Keats to His Family and Friends (edited by Sidney Colvin). London: Macmillan, 1925.[91]

- The Letters of John Keats (edited by Hyder Edward Rollins). (2 volumes), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958.

- Letters of John Keats: A new selection (edited by Robert Gittings). London, Oxford, & New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[92]

Poems by John Keats[]

A Thing Of Beauty by John Keats - Poetry Reading

ODE TO AUTUMN by John Keats - FULL AudioBook (Poem) Greatest AudioBooks

Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats Famous English Poems by Famous Poets Listen Free Audio Online

- The Eve of St. Agnes

- La Belle Dame sans Merci

- Ode on a Grecian Urn

- Ode on Indolence

- Ode on Melancholy

- Ode to a Nightingale

- Ode to Fancy

- Ode to Psyche

- On First Looking into Chapman's Homer

- On the Grasshopper and Cricket

- To Autumn

See also[]

References[]

- Bate, Walter Jackson (1964). John Keats. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Brown, Charles Armitage (1937). The Life of John Keats, ed. London: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, Sue (2009). Joseph Severn, A Life: The Rewards of Friendship. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199565023

- Colvin, Sidney (1917). John Keats: His Life and Poetry, His Friends Critics and After-Fame. London: Macmillan.

- Colvin, Sidney (1970). John Keats: His Life and Poetry, His Friends, Critics, and After-Fame. New York: Octagon Books.

- Coote, Stephen (1995). John Keats. A Life. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- De Almeida, Hermione. Romantic Medicine and John Keats. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0195063074

- Gittings, Robert (1954). John Keats: The Living Year. 21 September 1818 to 21 September 1819. London: Heinemann.

- Gittings, Robert (1964). The Keats Inheritance. London: Heinemann.

- Gittings, Robert (1968). John Keats. London: Heinemann.

- Gittings, Robert (1987) Selected poems and letters of Keats London: Heinemann.

- Goslee, Nancy (1985). Uriel's Eye: Miltonic Stationing and Statuary in Blake, Keats and Shelley. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0243-3

- Hewlett, Dorothy (3rd rev. ed. 1970). A life of John Keats. London: Hutchinson.

- Hirsch, Edward (Ed). (2001). Complete Poems and Selected Letters of John Keats. Random House Publishing. ISBN 0-3757-5669-8

- Houghton, Richard (Ed). (2008). The Life and Letters of John Keats. Read Books.

- Jones, Michael (1984). "Twilight of the Gods: The Greeks in Schiller and Lukacs". Germanic Review 59 (2): 49-56. doi:10.1080/00168890.1984.9935401.

- Lachman, Lilach (1988). "History and Temporalization of Space: Keats' Hyperion Poems". Proceedings of the XII Congress of the International Comparative Literature Association, edited by Roger Bauer and Douwe Fokkema (Munich, Germany): 159-164.

- G. M. Matthews, ed. (1995). "John Keats: The Critical Heritage". London: Routledge. ISBN 0-4151-3447-1

- Monckton Milnes, Richard, ed. (Lord Houghton) (1848). Life, Letters and Literary Remains of John Keats. 2 vols. London: Edward Moxon.

- Motion, Andrew (1997). Keats. London: Faber.

- O'Neill, Michael & Mahoney Charles (ed.s) (2007). Romantic Poetry: An Annotated Anthology. Blackwell. ISBN 0-6312-1317-1

- Ridley, M. and R. Clarendon (1933). Keats' craftsmanship: a study in poetic development ASIN: B00085UM2I (Out of Print in 2010).

- Scott, Grant F. (1994). The Sculpted Word: Keats, Ekphrasis, and the Visual Arts. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. ISBN 0-87451-679-X

- Stillinger, Jack (1982). Complete Poems. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6741-5430-4

- Strachan, John (Ed) (2003). A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on the Poems of John Keats. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-3478-6

- Vendler, Helen, (1983). The Odes of John Keats. Belknap Press ISBN 0674630769

- Walsh, John Evangelist (1999). Darkling I Listen: The Last Days and Death of John Keats. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Walsh, William (1957). "John Keats", in From Blake to Byron. Middlesex: Penguin.

- Ward, Aileen (1963). John Keats: The Making of a Poet. London: Secker & Warburg.

- Wolfson, Susan J. (1986). The Questioning Presence. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1909-3

- Kirkland, John (2008). Love Letters of Great Men, Vol. 1. CreateSpace Publishing.

- Lowell, Amy (1925). John Keats. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Parson, Donald (1954). Portraits of Keats. Cleveland: World Publishing Co.

- Plumly, Stanley (2008). Posthumous Keats. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Richardson, Joanna (1963). The Everlasting Spell. A Study of Keats and His Friends. London: Cape

- Richardson, Joanna (1980). Keats and His Circle. An Album of Portraits. London: Cassell.

- Rossetti, William Michael (1887). The Life and Writings of John Keats. London: Walter Scott.

- Turley, Richard Marggraf (2004). Keats' Boyish Imagination. London: Routledge, ISBN 9780415288828

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 John William Cousin, "Judd, Sylvester," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 218. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 1, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 O'Neill and Mahoney (1988), 418.

- ↑ This Craft of Verse, Jorge Luis Borges, (Harvard University Press, 2000), page 98-101

- ↑ Motion (1997), 10

- ↑ Gittings (1968), 11

- ↑ Harrow. Motion (1998), 22.

- ↑ Milnes (1848)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Gittings (1987) pp1-3

- ↑ Monckton Milnes (1848) pxiii

- ↑ Motion 1999, 46.

- ↑ Motion (1998), p98

- ↑ Motion (1997) p94

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hirsch, Edward (2001)

- ↑ Colvin (2006) p35

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p155

- ↑ Motion (1997) p116-120

- ↑ Motion (1997) p130

- ↑ Keats letter to Benjamin Bailey, November 22nd, 1817

- ↑ On 11 April 1819, Keats and Coleridge had a long walk together over the Heath. Keats says in a letter to his brother George, that they talked about "a thousand things,... nightingales, poetry, poetical sensation, metaphysics". Motion (1997), 365-66

- ↑ New York Times article: Tracing the Keats Family in America; Koch 30 July 1922.). Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Motion (1997) p494

- ↑ Letter of 7 August 1818; Brown (1937)

- ↑ Motion (1997) p290

- ↑ Zur Pathogenie der Impetigines. Auszug aus einer brieflichen Mitteilung an den Herausgeber. [Müller's] Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin. 1839, page 82.

- ↑ "Consumption" was not identified as a single disease until 1820 and there was considerable stigma attached to the infection, often being associated with weakness, repressed sexual passion or masturbation. Keats "refuses to give it a name" in his letters. De Almeida (1991), 206-07; Motion (1997), 500-01

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 O'Neill and Mahoney (1988), 419

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 "Keats, John" The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Edited by Dinah Birch. Oxford University Press Inc.

- ↑ The original mulberry tree no longer survives, though others have been planted since.

- ↑ Hart, Christopher. (2 August 2009.) "Savour John Keats' poetry in garden where he wrote". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Bate (1963) p63

- ↑ The Quarterly Review. April 1818. 204-208

- ↑ Extracts from Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, 3 (1818) p519-24". Nineteenth Century Literary Manuscripts, Part 4. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p504

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Kennedy, Maev. "Keats's London home reopens after major refurbishment". The Guardian, 22 July 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p262

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p268

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p264

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p139

- ↑ Walsh William (1981) Introduction to Keats Law Book Co of Australasia p81

- ↑ Gittings (1956) Mask of Keats. Heinmann p45

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Gittings (1968), 293-298

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Gittings (1968) p327-331

- ↑ Richardson, 1952, p. 112

- ↑ Bate (1964) p636

- ↑ Motion (1997) p496

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "A window to the soul of John Keats" by Marsh, Stefanie. The Times, 2 November 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Brown (2009)

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Flood, Alison. "Doctor's mistakes to blame for Keats's agonising end, says new biography". The Guardian, 26 October 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Colvin (1917) p208

- ↑ Adonais: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats. Representative Poetry Online. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Richardson, 1952, p89.

- ↑ "Keats's keeper". Motion, Andrew. The Guardian, 7 May 2005. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "John Keats," Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., Britannica.com, Web, Mar. 18, 2012.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Andrew Motion (23 January 2010). "Article 23 January 2010 An introduction to the poetry of John Keats". London: Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/jan/23/john-keats-andrew-motion. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ↑ Strachan (2003), p2

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Walsh (1957), 220-221

- ↑ Keats Letter To Percy Bysshe Shelley, 16 August 1820

- ↑ Adonaïs by Shelley is a despairing elegyof 495 lines and 55 Spenserian stanzas. It was published that July 1820 and he came to view it as his "least imperfect" work.

- ↑ Adonaïs (Adonaïs: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, Author of Endymion, Hyperion, etc.) by Shelley, published 1821

- ↑ University of Toronto -Adonaïs by Shelley

- ↑ Bryon, Letters and Journals (edited by Rowland E. Prothero), (1898-1901) 5:93. in notes to Margaret Holford, "To Mrs. *. *******. On receiving from her a beautiful Sketch of Lake Scenery, the Production of her own Pencil," English Poetry, 1579-1830, Center for Applied TEchnologies in the Humanities, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University. Web, July 10, 2016.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 62.5 Gittings (1987) pp18-21

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 63.5 63.6 Gittings (1987) pp12-17

- ↑ Strachan (2003) p12

- ↑ T.S. Eliot The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism (1933)

- ↑ Gittings (1968) p266

- ↑ Letter to George Keats, Sunday 14 February 1819

- ↑ Scott, Grant (ed.), Selected Letters of John Keats, Harvard University Press (2002)

- ↑ Wu, Duncan (2005) Romanticism: an anthology: Edition: 3, illustrated. Blackwell, 2005 p.1351. citing Letter to George Keats. Sunday, 21 December 1817

- ↑ Keats letter to Benjamin Bailey, Saturday 22 November 1817

- ↑ Houghton (2008), 184

- ↑ Bate p581

- ↑ Baynes, Thomas (Ed.). Encyclopedia Britannica Vol XIV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1888. OCLC 1387837. 23

- ↑ Tennyson was writing Keats-style poetry in the 1830s and was being critically attacked in the same manner as his predecessor.

- ↑ "Dictionary of Literary Biography on Richard Monckton Milnes," BookRags.com, Web, Oct. 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Keats, John". Encyclopedia Britannica, Ninth Edition, Vol. XIV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1882. 22-24

- ↑ Alphabetical list of authors: Jago, Richard to Milton, John. Arthur Quiller-Couch, editor, Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919). Bartleby.com, Web, May 18, 2012.

- ↑ Vendler (1933)

- ↑ Bate (1963)

- ↑ Ridley & Clarendon (1933)

- ↑ John Keats, People, History, Westminster Abbey. Web, July 12, 2016.

- ↑ The Keats-Shelley Poetry Award. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Gittings (1968), 3

- ↑ Gittings (1968), 5

- ↑ Motion (1997), 499

- ↑ The Poetical Works of John Keats (1884), Internet Archive, Web, Oct. 20, 2012.

- ↑ The Poetical Works of John Keats, Bartleby.com. Web, Apr. 20, 2013.

- ↑ Poems by John Keats 1896). Internet Archive. Web, July 1, 2013.

- ↑ Search results = au:Heathcote William Garrod, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Mar. 3, 2016.

- ↑ Letters of John Keats to Fanny Brawne: Written in the Years of MDCCCXIX and MDCCCXX (1901), Internet Archive, Web, Oct. 20, 2012.

- ↑ Letters of John Keats to His Family and Friends, Project Gutenberg. Web, Sep. 9, 2013.

- ↑ John Keats 1795-1821, Poetry Foundation, Web, Oct. 20, 2012.

External links[]

- Poems

- 5 poems by Keats: "You say you love, but with a voice," "To Autumn," "In a drear-nighted December," "O, thou whose face has felt the winter's wind," "On the Grasshopper and Cricket"

- John Keats in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900: 15 poems ("Song of the Indian Maid," "Ode to a Nightingale," "Ode on a Grecian Urn," "Ode to Psyche," "To Autumn," "Ode on Melancholy," "Fragment of an Ode to Maia," "Bards of Passion and of Mirth," "Fancy," "Stanzas," "Las Belle Dame sans Merci," "On first looking into Chapman's Homer," "When I have Fears that I may cease to be," "To Sleep," "Last Sonnet")

- Keats in The English Poets: An anthology: The Flight (from "The Eve of St. Agnes"), "Ode to a Nightingale," "Ode on a Grecian Urn," "Ode": 'Bard of passion and of mirth', "To Autumn," "Lines on the Mermaid Tavern," The Bard Speaks (from The Epistle to My Brother, George)

- from Miscellaneous Poems: "Endymion," "Cynthia's Bridal Evening,"

- Extracts from Endymion: Beauty, Hymn to Pan, Bacchus

- Extracts from Hyperion: Saturn, Cœlus to Hyperion, Oceanus, Hyperion's Arrival

- Sonnets: "On First Looking into Chapma's Homer," "Written in January, 1817," "Written in January, 1818," "Addressed to Haydon," "On the Grasshopper and the Cricket," "The Human Seasons," "On a Picture of Leander," Keats's Last Sonnet

- John Keats (1795-1821) info & 17 poems at English Poetry, 1579-1830

- Keats, John (1795-1821) (25 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- John Keats biography & 20 poems at the Academy of American Poets.

- John Keats 1795–1821 at the Poetry Foundation

- John Keats at the Literature Network

- John Keats at PoemHunter (220 poems)

- John Keats at Poetry Nook (242 poems)

- Books

- The Poetical Works of John Keats at Bartleby.com

- Works by John Keats at Project Gutenberg

- Works by John Keats at the Internet Archive

- Audio / video

- John Keats poems at YouTube

- About

- John Keats in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Keats, John in the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica

- John Keats at NNDB

- John Keats at Biography.com

- The Life and Work of John Keats 1795-1821

- Critical Introduction by Matthew Arnold

- John-Keats.com

- Keats' Kingdom

- John Keats at the British Library

- The Harvard Keats Collection at the Houghton Library

- Keats House museum, Hampstead

- The Keats-Shelley House museum in Rome

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

| This page uses content from Wikinfo . The original article was at Wikinfo:John Keats. The list of authors can be seen in the (view authors). page history. The text of this Wikinfo article is available under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license. |

|