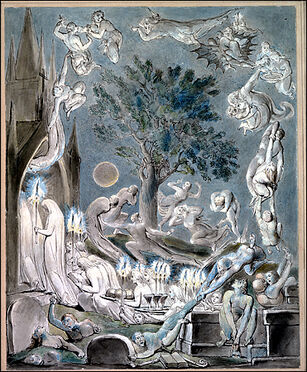

Watercolour illustration by William Blake for The Grave, 1805. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| Robert Blair | |

|---|---|

| Born |

17 April 1699 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 4 February 1746 |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | poet |

| Notable works | The Grave (1743) |

Robert Blair (17 April 1699 - 4 February 1746) was a Scottish poet.

Life[]

Overview[]

Blair was born at Edinburgh, where his father was a clergyman, and became minister of Athelstaneford, Haddingtonshire. His sole work was The Grave, a poem in blank verse extending to 767 lines of very various merit, in some passages rising to great sublimity, and in others sinking to commonplace. It was illustrated by William Blake. Blair's son, Robert, was a very distinguished Scottish judge and Lord President of the Court of Session; and his successor in his ministerial charge was Home, the author of Douglas.[1]

Family, youth, education[]

Blair was born in Edinburgh, the eldest son of Rev. David Blair, a minister of the old church of Edinburgh, and a chaplain to the king. His mother's maiden name was Euphemia Nisbet, daughter of Alexander Nisbet of Carfin. Hugh Blair, the writer on oratory, was his 1st cousin. David Blair died in his son's infancy, on 10 June 1710.[2]

Robert was educated at the University of Edinburgh, and took a degree in Holland. Nothing has been discovered with regard to the details of either curriculum. From about 1718 to 1730 he seems to have lived in Edinburgh as an unemployed probationer, having received license to preach, 15 Aug. 1729. In the second part of a miscellany, entitled Lugubres Cantus,' published at Edinburgh in 1719, there occurs an "Epistle to Robert Blair," which adds nothing to our particular information.[2]

He is believed to have belonged to the Athenian Society, a small literary club in Edinburgh, which published in 1720 the Edinburgh Miscellany.[2] The pieces in this volume are anonymous, but family tradition has attributed to Robert Blair 2 brief paraphrases of scripture which it contains, and Calender, its editor, is known to have been his close friend.[3]

Career[]

In 1728 he published, in a quarto pamphlet, a Poem dedicated to the Memory of William Law, professor of philosophy in Edinburgh. This contained 140 lines of elegiac verse. In 1731 Blair was appointed to the living of Athelstaneford in East Lothian, to which he was ordained by the presbytery of Haddington on 5 Jan. of that year. In 1738 he married Isabella, the daughter of his deceased friend, Professor Law; she bore him 5 sons and a daughter, and survived him until 1774.[3]

He possessed a private fortune, and he gave up so much of his leisure as his duties would grant him to the study of botany and of the old English poets.[3]

Before he left Edinburgh he had begun to sketch a poem on the subject of the Grave. At Athelstaneford he leisurely composed this poem, and about 1742 began to make arrangements for its publication. He had formed the acquaintance of Dr. Isaac Watts, who had paid him, he says, "many civilities." He sent the manuscript of the ‘Grave’ to Dr. Watts, who offered it "to two different London booksellers, both of whom, however, declined to publish it, expressing a doubt whether any person living three hundred miles from town could write so as to be acceptable to the fashionable and the polite." In the same year, however, 1742, Blair wrote to Dr. Doddridge, and interested him in the poem, which was eventually published, in quarto, in 1743.[3]

The Grave enjoyed an instant and signal success, but Blair was neither tempted out of his solitude nor persuaded to repeat the experiment which had been so happy. His biographer says:

- His tastes were elegant and domestic. Books and flowers seem to have been the only rivals in his thoughts. His rambles were from his fireside to his garden; and, although the only record of his genius is of a gloomy character, it is evident that his habits and life contributed to render him cheerful and happy.[3]

He died of a fever on 4 February 1746, and was buried under a plain stone, which bears the initials R.B., in the churchyard of Athelstaneford. Although he had published so little, no posthumous poems were found in his possession, and his entire works do not amount to 1,000 lines.[3]

Writing[]

The Grave[]

The Grave was the first and best of a whole series of mortuary poems. In spite of the epigrams of conflicting partisans, Night Thoughts must be considered as contemporaneous with it, and neither preceding nor following it. There can be no doubt, however, that the success of Blair encouraged Edward Young to persevere in his far longer and more laborious undertaking.[4]

Blair’s verse is less rhetorical, more exquisite, than Young's, and, indeed, his relation to that writer, though too striking to be overlooked, is superficial. He forms a connecting link between Otway and Crabbe, who are his nearest poetical kinsmen.[4]

The Grave contains 767 lines of blank verse. It is very unequal in merit, but supports the examination of modern criticism far better than most productions of the 2nd quarter of the 18th century. As philosophical literature it is quite without value; and it adds nothing to theology; it rests solely upon its merit as romantic poetry.[4]

The poet introduces his theme with an appeal to the grave as the monarch whose arm sustains the keys of hell and death (1-10) ; he describes, in verse that singularly reminds us of the 17th century, the physical horror of the tomb (ll-27), and the ghastly solitude of a lonely church at night (28-44). He proceeds to describe the churchyard (45-84), bringing in the schoolboy "whistling aloud to keep his courage up," and the widow. This leads him to a reduction on friendship, and how sorrow’s crown of sorrow is put on in bereavement (85-110).[4]

The poetry up to this point has been of a very fine order; here it declines. A consideration of the social changes produced by death (111-122), and the passage of persons of distinction (123-155), leads on to a homily upon the vain pomp and show of funerals (156-182). Commonplaces about the devouring tooth of time (183-206) lead to the consideration that in the grave rank and precedency (207-236), beauty (237-256), strength (257-285), science (286-29(5), and eloquence (297-318) become a mockery and a jest; and the idle pretensions of doctors (Sli)-336) and of misers (337-368) are ridiculed.[4]

At this point the poem recovers its dignity and music. The terror of death is very nobly described (382-430), and the madness of suicides is scourged in verse which is almost Shakespearian (382-430). Our ignorance of the alter world (431-446), and the universality of death, with man's unconsciousness of his position (447-500), lead the poet to a fine description of the medley of death (501-5-10) and the brevity of life (5-11-599). The horror of the grave is next attributed to sin (600-633), and the poem closes somewhat feebly and ineffectually with certain timid and perfunctory speculations about the mode in which the grave will respond to the Resurrection trumpet.[4]

The poem is perhaps best known for the illustrations created by William Blake following a commission from Robert Cromek. Blake's designs were engraved by Luigi Schiavonetti, and published in 1808.

Critical introduction[]

Blair's singular little poem, which has perhaps been more widely read than any other poetical production of a writer who wrote no other poetry, was, it is said, rejected by several London publishers on the ground that it was "too heavy for the times." As its introducer was Dr. Watts, it is not likely that he suggested it to any but serious members of the trade. The Grave thus adds one to the tolerably long list of books respecting the chances of which professional judgment has been hopelessly out.

It acquired popularity almost as soon as it was published, and retained it for at least a century; indeed its date is not yet gone by in certain circles. Long after its author’s death it obtained an additional and probably a lasting hold on a new kind of taste by the fact of Blake’s illustrating it. The artist’s designs indeed were, as he expresses it in the beautiful Dedication to Queen Charlotte, rather ‘visions that his soul had seen’ than representations of anything directly contained in Blair’s verse. But that verse itself is by no means to be despised. Technically its only fault is the use and abuse of the redundant syllable.

The quality of Blair’s blank verse is in every respect rather moulded upon dramatic than upon purely poetical models, and he shows little trace of imitation either of Milton, or of his contemporary Thomson. Whether his studies—contrary to the wont of Scotch divines at that time—had really been much directed to the drama, I cannot say; but the perusal of his poem certainly suggests such a conclusion, not merely the licence just mentioned, but the generally declamatory and rhetorical tone helping to produce the impression.

The matter of the poem is good. General plan it has none, but in so short a composition a general plan is hardly wanted. It abounds with forcible and original ideas expressed in vigorous and unconventional phraseology, nor is it likely nowadays that this phraseology will strike readers, as it struck the delicate critics of the eighteenth century, as being ‘vulgar.’ Vigorous single lines are numerous; and it is at least as much a tribute to the vigour of the poem as to its popularity, that many of its phrases have worked their way into current speech. Nor is it difficult to produce sustained passages, the effect of which is marred only by the ugly technical fault already noticed.

The poem naturally invites comparison with the Night Thoughts. In depth of meaning it is probably the inferior of Young’s work. But its shortness is very much in its favour, as also is the absence of conventionality which distinguishes it, if we except a little stock satire about the trappings of the grave, &c. The wonder is however, not that Blair has sometimes fallen into the use of the cut and dried, but that he has so often avoided it. To have written a poem of seven or eight hundred lines on such a subject, which after the lapse of nearly a century and a half can be read with pleasure and even some admiration, is something; perhaps it is something by no means inconsiderable. It is due beyond all doubt to the fact that Blair had the specially poetic faculty of saying old things in a new way. There is almost always something novel in his dressing up of his images and a suggestive unhackneyedness in their expression. It is sufficient to read the last four lines of the poem to perceive this.[5]

Publications[]

Illustration by William Blake for The Grave (1805). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Poetry[]

- A Poem Dedicated to the Memory of the Late Learned and Eminent Mr. William Law, Professor of Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh. [Edinburgh?]: 1728.

- The Grave: A poem. London: M. Cooper, 1743.

- The Grave: A poem (illustrated by twelve etchings executed by L. Schiavonetti, from the original inventions of William Blake). London: R.H. Gromek, 1818; New York: D. Appleton, 1903.

- Poetical Works. London: John & Arthur Arch, 1794.

Collected editions[]

- The Works of Robert Blair; with the Life of the author. Stourport, UK: George Nicholson, 1814.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[6]

See also[]

Robert Blair's "The Grave" 1805 - William Blake

References[]

- See the biographical introduction prefixed to Blair's Poetical Works, by Dr Robert Anderson, in his Poets of Great Britain, vol. viii. (1794). The only modern edition of The Grave is that of Professor James A. Means, which was published in 1973 by the Augustan Reprint Society, Los Angeles.

Gosse, Edmund (1886) "Blair, Robert" in Stephen, Leslie Dictionary of National Biography 5 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 164-166 Wikisource, Web, Dec. 14, 2017.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Blair, Robert," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 38. Web, Dec. 14, 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gosse, 164.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Gosse, 165.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Gosse, 166.

- ↑ from George Saintsbury, "Critical Introduction: Robert Blair (1699–1746)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Feb. 22, 2016.

- ↑ Seaarch results = au:Robert Blair 1746, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Feb. 22, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- Blair, Robert ("The Grave" [excerpt]) at Representative Poetry Online

- Robert Blair at PoemHunter (2 (poems)

- Blair in The English Poets: An antholgy: Extracts from The Grave: Self-Murder, Omnes eodem cogimur, The Resurrection

- Robert Blair at Poetry Nook (5 poems)

- Audio / video

- Books

- Robert Blair at Amazon.com

- About

- Robert Blair in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Blair, Robert" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Blair, Robert at The Literary Gothic.

- Robert Blair in Lives of Scottish Poets

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Blair, Robert

|