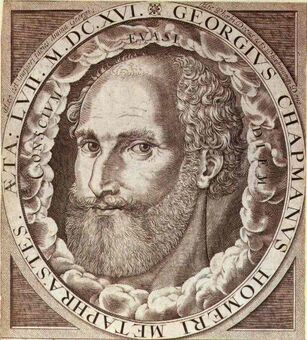

George Chapman (?1559-1634), engraving for The Whole Works of Homer. Attributed to William Hole (died 1624), 1616. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| George Chapman | |

|---|---|

| Born |

c. 1559 Hitchin, Hertfordshire, England |

| Died |

May 12, 1634 London |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | Elisabethan |

| Genres | Translation |

| Notable work(s) | Translations of Homer |

George Chapman (?1559 - 12 May 1634) was an English poet, dramatist, and translator. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been claimed as the Rival Poet of Shakespeare's sonnets, and as a precursor of the Metaphysical poets.

Life

Overview

Chapman was born near Hitchin, and probably educated at Oxford and Cambridge. He wrote many plays, including The Blind Beggar of Alexandria (1596), All Fools (1599), A Humerous Daye's Myrthe (1599), Eastward Hoe (with Ben Jonson), As a dramatist he has humour, and vigour, and occasional poetic fire, but is very unequal. His great work by which he lives in literature is his translation of Homer. The Iliad was pub. in 1611, the Odyssey in 1616, and the Hymns, etc., in 1624. The work is full of energy and spirit, and well maintains its place among the many later translations by men of such high poetic powers as Pope and Cowper, and others: and it had the merit of suggesting Keats's immortal Sonnet, in which its name and memory are embalmed for many who know it in no other way. Chapman also translated from Petrarch, and completed Marlowe's unfinished Hero and Leander.[1]

Youth and education

Chapman was born near Hitchin, Hertfordshire. The inscription on the portrait which forms the frontispiece of The Whole Works of Homer states that he was then (1616) 57 years of age. Anthony à Wood[2] says that about 1574 he was sent to the university, “but whether first to this of Oxon, or that of Cambridge, is to me unknown; sure I am that he spent some time in Oxon, where he was observed to be most excellent in the Latin and Greek tongues, but not in logic or philosophy.”[3]

Career

Chapman’s earliest extant play, The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, was produced in 1596, and 2 years later Francis Meres mentions him in Palladis Tamia among the “best for tragedie” and the “best for comedie.”[3]

Of his life between leaving the university and settling in London there is no account. It has been suggested, from the detailed knowledge displayed in The Shadow of Night of an incident in Sir Francis Vere’s campaign, that he saw service in the Netherlands.[3]

There are frequent entries with regard to Chapman in Henslowe’s diary for the years 1598-1599, but his dramatic activity slackened during the following years, when his attention was chiefly occupied by his Homer.[4]

In 1604 he was imprisoned with John Marston for his share in Eastward Ho, in which offence was given to the Scottish party at court. Ben Jonson voluntarily joined the 2, who were soon released. Chapman seems to have enjoyed favor at court, where he had a patron in Prince Henry, but in 1605 Jonson and he were for a short time in prison again for “a play.”[4]

Beaumont, the French ambassador in London, in a despatch of the 5th of April 1608, writes that he had obtained the prohibition of a performance of Biron in which the queen of France was represented as giving Mademoiselle de Verneuil a box on the ears. He adds that 3 of the actors were imprisoned, but that the chief culprit, the author, had escaped.[5] [4]

Among Chapman’s patrons was Robert Carr, earl of Somerset, to whom he remained faithful after his disgrace.[4]

Chapman enjoyed the friendship and admiration of his great contemporaries. John Webster in the preface to The White Devil praised “his full and heightened style,” and Ben Jonson told Drummond of Hawthornden that Fletcher and Chapman “were loved of him.” These friendly relations appear to have been interrupted later, for there is extant in the Ashmole MSS. an “Invective written by Mr George Chapman against Mr Ben Jonson.”[4]

With Shakespeare we should never have guessed that he had come at all in contact, had not the keen intelligence of William Minto divined or rather discerned him to be the rival poet referred to in Shakespeare’s sonnets with a grave note of passionate satire, hitherto as enigmatic as almost all questions connected with those divine and dangerous poems. This conjecture Prof. Minto fortified by such apt collocation and confrontation of passages that we may now reasonably accept it as an ascertained and memorable fact.[4]

Chapman died in the parish of St. Giles in the Fields, and was buried on the 12th of May 1634 in the churchyard.[4]

Writing

Chapman, his earliest biographer is careful to let us know, “was a person of most reverend aspect, religious and temperate, qualities rarely meeting in a poet”; he had also certain other merits at least as necessary to the exercise of that profession.[4]

He had a singular force and solidity of thought, an admirable ardor of ambitious devotion to the service of poetry, a deep and burning sense at once of the duty implied and of the dignity inherent in his office; a vigor, opulence, and loftiness of phrase, remarkable even in that age of spiritual strength, wealth and exaltation of thought and style; a robust eloquence, touched not infrequently with flashes of fancy, and kindled at times into heat of imagination.[4]

The main fault of his style is more commonly found in the prose than in the verse of his time,— a quaint and florid obscurity, rigid with elaborate rhetoric and tortuous with labyrinthine illustration; not dark only to the rapid reader through closeness and subtlety of thought (like Donne, whose miscalled obscurity is so often “all glorious within”) but thick as a witch’s gruel with forced and barbarous eccentricities of articulation.[4]

From his occasional poems an expert and careful hand might easily gather a noble anthology of excerpts, chiefly gnomic or meditative, allegoric or descriptive.[4]

So much it may suffice to say of Chapman as an original poet, one who held of no man and acknowledged no master, but from the birth of Marlowe well-nigh to the death of Jonson held on his own hard and haughty way of austere and sublime ambition, not without kindly and graceful inclination of his high grey head to salute such younger and still nobler compeers as Jonson and Fletcher.[4]

Tragedies

The most notable examples of his tragic work are comprised in the series of plays taken, and adapted sometimes with singular licence, from the records of such part of French history as lies between the reign of Francis I. and the reign of Henry IV., ranging in date of subject from the trial and death of Admiral Chabot to the treason and execution of Marshal Biron. The 2 plays bearing as epigraph the name of that famous soldier and conspirator are a storehouse of lofty thought and splendid verse, with scarcely a flash or sparkle of dramatic action.[4]

The only play of Chapman’s whose popularity on the stage survived the Restoration is Bussy d’Ambois (d’Amboise),— a tragedy not lacking in violence of action or emotion, and abounding even more in sweet and sublime interludes than in crabbed and bombastic passages. His rarest jewels of thought and verse detachable from the context lie embedded in the tragedy of Caesar and Pompey, from which the finest of them were first extracted by the unerring and unequalled critical genius of Charles Lamb.[4]

In most of his tragedies the lofty and laboring spirit of Chapman may be said rather to shine fitfully through parts than steadily to pervade the whole; they show nobly altogether as they stand, but even better by help of excerpts and selections.[4]

As his language in the higher forms of comedy is always pure and clear, and sometimes exquisite in the simplicity of its earnest and natural grace, the stiffness and density of his more ambitious style may perhaps be attributed to some pernicious theory or conceit of the dignity proper to a moral and philosophic poet. Nevertheless, many of the gnomic passages in his tragedies and allegoric poems are of singular weight and beauty; the best of these, indeed, would not discredit the fame of the very greatest poets for sublimity of equal thought and expression: witness the lines chosen by Shelley as the motto for a poem, and fit to have been chosen as the motto for his life.[4]

Comedies

But the excellence of his best comedies can only be appreciated by a student who reads them fairly and fearlessly through, and, having made some small deductions on the score of occasional pedantry and occasional indecency, finds in All Fools, Monsieur d’Olive, The Gentleman Usher, and The Widow’s Tears a wealth and vigour of humorous invention, a tender and earnest grace of romantic poetry, which may atone alike for these passing blemishes and for the lack of such clear-cut perfection of character and such dramatic progression of interest as we find only in the yet higher poets of the English heroic age.[4]

Chapman's Homer

The Whole Works of Homer, 1616. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The romantic and sometimes barbaric grandeur of Chapman’s Homer remains attested by the praise of Keats, of Coleridge and of Lamb; it is written at a pitch of strenuous and laborious exaltation, which never flags or breaks down, but never flies with the ease and smoothness of an eagle native to Homeric air.[4]

The objections which a just and adequate judgment may bring against Chapman’s master-work, his translation of Homer, may be summed up in 3 epithets: it is romantic, laborious, Elizabethan. The qualities implied by these epithets are the reverse of those which should distinguish a translator of Homer; but setting this apart, and considering the poems as in the main original works, the superstructure of a romantic poet on the submerged foundations of Greek verse, no praise can be too warm or high for the power, the freshness, the indefatigable strength and inextinguishable fire which animate this exalted work, and secure for all time that shall take cognizance of English poetry an honoured place in its highest annals for the memory of Chapman.[4]

Other plays

Grave of George Chapman in the Church of St. Giles, London. The tombstone was designed and paid for by Inigo Jones

Chapman's authorship has been argued in connection with a number of anonymous plays of his era.[6] F.G. Fleay proposed that his earliest play was The Disguises. He has been put forward as the author, in whole or in part, of Sir Giles Goosecap, Two Wise Men And All The Rest Fools, The Fountain Of New Fashions, and The Second Maiden's Tragedy.Of these, only Sir Gyles Goosecap'is generally accepted by scholars to have been written by Chapman (The Plays of George Chapman: The Tragedies, with Sir Giles Goosecap, edited by Allan Holaday, University of Illinois Press, 1987).

In 1654, bookseller Richard Marriot published the play Revenge for Honour as the work of Chapman. Scholars have rejected the attribution; the play may have been written by Henry Glapthorne. Alphonsus Emperor of Germany (also printed 1654) is generally considered another false Chapman attribution.[7]

The lost plays The Fatal Love and A Yorkshire Gentlewoman And Her Son were assigned to Chapman in Stationers' Register entries in 1660. Both of these plays were among those destroyed in the famous kitchen burnings by John Warburton's cook. The lost play Christianetta (registered 1640) may have been a collaboration between Chapman and Richard Brome, or a revision by Brome of a Chapman work.

Critical introduction

by Andrew Lang

In spite of the force and originality of English dramatic poetry in the age of Shakespeare, the poetical character of the time had much in common with the Alexandrian epoch in Greek literary history. At Alexandria, when the creative genius of Greece was almost spent, literature became pedantic and obscure. Poets desired to show their learning, their knowledge of the details of mythology, their acquaintance with the more fantastic theories of contemporary science. The same faults mark the poetry of the Elizabethan age, and few writers were more culpably Alexandrian than George Chapman. The spirit of Callimachus or of Lycophron seems at times to have come upon him, as the lutin was supposed to whisper ideas extraordinarily good or evil, to Corneille. When under the influence of this possession, Chapman displayed the very qualities and unconsciously translated the language of Callimachus. He vowed that he detested popularity, and all that can please "the commune reader." He inveighed against the "invidious detractor" who became a spectre that dogged him in every enterprise. He hid his meaning in a mist of verbiage, within a labyrinth of conceits, and himself said, only too truly, about the "sweet Leander" of Marlowe,

- ‘I in floods of ink

- Must drown thy graces.’

It is scarcely necessary to justify these remarks by illustrations from Chapman’s works. Every reader of the poems and the prefaces finds barbarism, churlish temper, and pedantry in profusion. In spite of unpopularity, Chapman "rested as resolute as Seneca, satisfying himself if but a few, if one, or if none like" his verses.

Why then is Chapman, as it were in his own despite, a poet still worthy of the regard of lovers of poetry? The answer is partly to be found in his courageous and ardent spirit, a spirit bitterly at odds with life, but still true to its own nobility, still capable, in happier moments, of divining life’s real significance, and of asserting lofty truths in pregnant words.

In his poems we find him moving from an exaggerated pessimism, a pessimism worthy of a Romanticist of 1830, to more dignified acquiescence in human destiny. The Shadow of Night, his earliest work, expresses, not without affectation and exaggeration, his blackest mood. Chaos seems better to him than creation, the undivided rest of the void is a happier thing than the crowded distractions of life. Night, which confuses all in shadow and rest, is his Goddess,

‘That eagle-like doth with her starry wings,

Beat in the fowls and beasts to Somnus’ lodgings,

And haughty Day to the infernal deep,

Proclaiming silence, study, ease, and sleep.’

As for day,

‘In hell thus let her sit, and never rise,

Till morns leave blushing at her cruelties.’

In a work published almost immediately after The Shadow of Night, in Ovid’s Banquet of Sense, Chapman "consecrates his strange poems to those searching spirits whom learning hath made noble." Nothing can well be more pedantic than the conception of the Banquet of Sense. Ovid watches Julia at her bath, and his gratification is described in a singular combination of poetical and psychological conceits. Yet in this poem, the redeeming qualities of Chapman and the soothing influence of that anodyne which most availed him in his contest with life, are already evident. Learning is already beginning to soothe his spirit with its spell. To Learning, as we shall see, he ascribed all the excellences which a modern critic assigns to culture. Learning, in a wide and non-natural sense, is his stay, support, and comfort. In the Banquet of Sense, too, he shows that patriotic pride in England, that enjoyment of her beauty, which dignify the Carmen Epicum, de Guiana, and appear strangely enough in the sequel of Hero and Leander. There are exquisite lines in the Banquet of Sense, like these, for example, which suggest one of Giorgione’s glowing figures:—

- ‘She lay at length like an immortal soul,

- At endless rest in blest Elysium.’

But Chapman’s interest in natural science breaks in unseasonably —

- ‘Betwixt mine eye and object, certain lines

- Move in the figure of a pyramis,

- Whose chapter in mine eye’s gray apple shines,

- The base within my sacred object is;’

— singular reflections of a lover by his lady’s bower!

Chapman could not well have done a rasher thing than ‘suppose himself executor to the unhappily deceased author of’ Hero and Leander. A poet naturally didactic, Chapman dwelt on the impropriety of Leander’s conduct, and confronted him with the indignant goddess of Ceremony. In a passage which ought to interest modern investigators of Ceremonial Government, the poet makes ‘all the hearts of deities’ hurry to Ceremony’s feet:—

- ‘She led Religion, all her body was

- Clear and transparent as the purest glass;

- Devotion, Order, State, and Reverence,

- Her shadows were; Society, Memory;

- All which her sight made live, her absence die.’

The allegory is philosophical enough, but strangely out of place.The poem contains at least one image worthy of Marlowe —

‘His most kind sister all his secrets knew,

And to her, singing like a shower, he flew.’

This too, of Hero, might have been written by the master of verse:—

‘Her fresh heat blood cast figures in her eyes,

And she supposed she saw in Neptune’s skies

How her star wander’d, washed in smarting brine,

For her love’s sake, that with immortal wine

Should be embathed, and swim in more heart’s-ease,

Than there was water in the Sestian seas.’

It is in The Tears of Peace (1609), an allegory addressed to Chapman’s patron, the short-lived Henry, Prince of Wales, that the poet does his best to set forth his theory of life and morality. He "sat to it," he says, to his "criticism of life," and he was guided in his thoughts by his good genius, Homer. Inspired by Homer, he rises above himself, his peevishness, his controversies, his angry contempt of popular opinion, and he beholds the beauty of renunciation, and acquiesces in a lofty stoicism:—

- ‘Free suffering for the truth makes sorrow sing,

- And mourning far more sweet than banquetting.’

He comforts himself with the belief that Learning, rightly understood, is the remedy against discontent and restlessness:—

- ‘For Learning’s truth makes all life’s vain war cease.’

It is Learning that

- ‘Turns blood to soul, and makes both one calm man.’

By Learning man reaches a deep knowledge of himself, and of his relations to the world, and ‘Learning the art is of good life’:—

- ‘Let all men judge, who is it can deny

- That the rich crown of old Humanity

- Is still your birthright? and was ne’er let down

- From heaven for rule of beasts’ lives, but your own?’

These noble words still answer the feverish debates of the day, for, whatever our descent,

- ‘Still, at the worst, we are the sons of men!’

In this persuasion, Chapman can consecrate his life to his work, can cast behind him fear and doubt,

- ‘This glass of air, broken with less than breath,

- This slave bound face to face to death till death.’

His work was that which the spirit of Homer put upon him, in the green fields of Hitchin.

- ‘There did shine,

- A beam of Homer’s freër soul in mine,’

he says, and by virtue of that beam, and of his devotion to Homer, George Chapman still lives. When he had completed his translations he could say,

- ‘The work that I was born to do, is done.’

Learning and work had been his staff through life, and had won him immortality. But for his Homer, Chapman would only be remembered by professional students. His occasional inspired lines would not win for him many readers. But his translations of the Iliad and Odyssey are masterpieces, and cannot die.

Chapman’s theory of translation allowed him great latitude. He conceived it to be "a pedantical and absurd affectation to turn his author word for word," and maintained that a translator, allowing for the different genius of the Greek and English tongues, "must adorn" his original "with words, and such a style and form of oration, as are most apt for the language into which they are converted." This is an unlucky theory, for Chapman’s idea of "the style and form of oration most apt for" English poetry was remote indeed from the simplicity of Homer. The more he admired Homer, the more Chapman felt bound to dress him up in the height of rhetorical conceit. He excused himself by the argument, that, we have not the epics as Homer imagined them, that "the books were not set together by Homer." He probably imagined that, if Homer had had his own way with his own works, he would have produced something much more in the Chapman manner, and he kindly added, ever and anon, a turn which he fancied Homer would approve. The English reader must be on his guard against this custom of Chapman’s, and must remember, too, that the translator’s erudition was exceedingly fantastic....

Chapman has another great fault, allied indeed to a great excellence. In his speed, in the rapidity of the movement of his lines, he is Homeric. The last twelve books of the Iliad were struck out at a white heat, in fifteen weeks. Chapman was carried away by the current of the Homeric verse, and this is his great saving merit. Homer inspires him, however uncouth his utterance, as Apollo inspired the Pythoness. He "speaks out loud and bold," but not clear. In the heat of his hurry, Chapman flies at any rhyme to end his line, and then his rhyme has to be tagged on by the introduction of some utterly un-Homeric mode of expression. Thus, in Chapman, the majestic purity of Homer is tormented, the bright and equable speed of the river of verse leaps brawling over rocks and down narrow ravines. What can be more like Chapman, and less like Homer, than these lines in the description of the storm,

- ‘How all the tops he bottoms with the deeps,

- And in the bottoms all the tops he steeps’?

Here the Greek only says "Zeus hath troubled the deep." It is thus that Chapman "adorns his original." Faults of this kind are perhaps more frequent in the Iliad than in the Odyssey. Coleridge’s taste was in harmony with general opinion when he preferred the latter version, with its manageable metre, to the ruder strain of the Iliad, of which the verse is capable of degenerating into an amble, or dropping into a trot.

The crudities, the inappropriate quaintnesses of Chapman’s Homer, are visible enough, when we read only a page or two, here and there, in the work. Neither Homer, nor any version of Homer, should be studied piece-meal. "He must not be read," as Chapman truly says, "for a few lines with leaves turned over capriciously in dismembered fractions, but throughout; the whole drift, weight, and height of his works set before the apprehensive eyes of his judge." Thus read, the blots on Chapman’s Homer almost disappear, and you see "the massive and majestic memorial, where for all the flaws and roughnesses of the weather-beaten work the great workmen of days unborn would gather to give honour to his name."[8]

Quotations

From All Fooles, II.1.170-178, by George Chapman:

- I could have written as good prose and verse

- As the most beggarly poet of 'em all,

- Either Accrostique, Exordion,

- Epithalamions, Satyres, Epigrams,

- Sonnets in Doozens, or your Quatorzanies,

- In any rhyme, Masculine, Feminine,

- Or Sdrucciola, or cooplets, Blancke Verse:

- Y'are but bench-whistlers now a dayes to them

- That were in our times....

Recognition

Chapman was buried in the churchyard of St. Giles in the Fields, where a monument to his memory was erected by Inigo Jones.[4]

Chapman is best known by the sonnet, "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer," which poet John Keats wrote for his friend Charles Cowden Clarke in October 1816. The poem, which begins "Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold," is much quoted (for example, by P.G. Wodehouse in his review of the earliest Flashman novel that came to his attention: "Now I understand what that ‘when a new planet swims into his ken’ excitement is all about.")[9] Arthur Ransome uses two references from the poem in his children's books, the Swallows and Amazons series.[10]

In Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem, The Revolt of Islam, Shelley quotes a verse of Chapman's as homage within his dedication "to Mary__ __" (presumably his wife Mary Shelley):

There is no danger to a man, that knows

What life and death is: there's not any law

Exceeds his knowledge; neither is it lawful

That he should stoop to any other law.[11]

Irish playwright Oscar Wilde quoted the same verse in his part fiction, part literary criticism, "The Portrait of Mr. W.H.".[12]

Chapman's poem "Bridal Song" was included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[13]

Publications

Poetry

- Ekìa vuktòs The Shadow of Night: Containing two poeticall hymnes. London: Printed by R. F. for William Ponsonby, 1594.

- Ouids Banquet of Sence. London: I.R. for Richard Smith, 1595.

- Hero and Leander (parts 1-2 by Christopher Marlowe, parts 3-6 by Chapman). London: Felix Kingston for Paule Linley, 1598.

- An Epicede, or Funerall Song: On the most disastrous death, of the highborne prince of men, Henry, Prince of Wales. London: T.S. for John Budge, 1612.

- Evgenia: Or Trve Nobilities Trance; For the Most Memorable Death, of the Thrice Noble and Religious; William Lord Rvssel. London, 1614.

- Poems (edited by Phyllis Brooks Bartlett). New York: Modern Language Association of America / London: Oxford University Press, 1941.

Plays

- The Blinde Begger of Alexandria. London: J. Roberts for William Jones, 1598.

- A Pleasant Comedy Entituled: An humerous dayes myrth. London: G.C. for Valentine Syms, 1599.

- Al Fooles. London: Printed by G. Eld for Thomas Thorpe, 1605.

- Eastward Hoe (by Chapman, Ben Jonson, & John Marston). London: G. Eld for William Aspley, 1605.

- Sir Gyles Goosecappe, Knight. London: John Windet for Edward Blunt, 1606.

- The Gentleman Usher. London: Valentine Simmes for Thomas Thorppe, 1606.

- Monsievr D'Olive. London: Thomas Creede for William Holmes, 1606.

- Bussy D'Ambois. London: Eliot's Court Press for William Aspley, 1607.

- The Conspiracie, and Tragedie of Charles, Duke of Byron. London: George Eld for Thomas Thorppe, 1608.

- Evthymiæ Raptvs; or, The teares of peace. London: H. Lownes for Richard Bonian & H. Walley, 1609.

- May-day. London: William Stansby for John Browne, 1611.

- The Widdowes Teares: A comedy. London: Printed by William Stansby for John Browne, 1612.

- The Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois. London: T. Snodham for John Helme, 1613.

- The Memorable Maske of the Honorable Houses or Inns of Court; the Middle Temple, and Lyncolns Inne. London: George Eld for George Norton, 1613.

- Andromeda Liberata. Or The Nvptials of Persevs and Andromeda. London: Printed by Eliot's Court Press for Laurence L'Isle, 1614.

- A Free and Offenceles Iustification, of a Lately Pvblisht and Most Maliciously Misinterpreted Poeme: Entitvled Andromeda Liberata. London: Printed by Eliot's Court Press for Laurence L'Isle, 1614.

- Pro Vere, Avtvmni Lachrymae. Inscribed to the Immortal Memorie of the most Pious and Incomparable Souldier, Sir Horatio Vere, Knight. London: Printed by B. Alsop for Th. Walkley, 1622.

- A Iustification of a Strange Action of Nero. London: Printed by Thomas Harper, 1629.

- Caesar and Pompey. London: Printed by Thomas Harper, sold by G. Emondson & T. Alchorne, 1631.

- The Tragedy of Chabot Admirall of France (by Chapman & James Shirley). London: Printed by Thomas Cotes for Andrew Crooke & William Cooke, 1639.

- The Comedies and Tragedies (edited by Richard Shepherd). (3 volumes), London: John Pearson, 1873. Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3.

- Plays

- volume 1 (edited by Allan Holaday and Michael Kiernan). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1970

- volume 2 (edited by Allan Holaday, G. Blakemore Evans, and Thomas Berger), Woodbridge, UK & Wolfeboro, NH: D. S. Brewer, 1987.

Translated

- Seaven Bookes of the Iliades of Homere, Prince of Poets (from books 1, 2, 7-11 of Homer's Iliad). London: John Windet, 1598.

- Achilles Shield (from book 18 of Homer's Iliad). London: John Windet, 1598.

- Homer Prince of Poets (from books 1-12 of Homer's Iliad). London: H. Lownes for Samuel Macham, 1609.

- The Iliad of Homer (all 24 books of Homer's Iliad). London: Richard Field for Nathaniell Butter, 1611

- Petrarchs Seven Penitentiall Psalms: Paraphrastically translated; with other philosophicall poems. London: R. Field for Matthew Selman, 1612.

- The Whole Works of Homer Prince of Poetts translated by Chapman. London: R. Field & W. Jaggard for Nathaniell Butter, [1616?]

- The Divine Poem of Musaeus. London: R. Field & W. Jaggard, 1616.

- The Georgicks of Hesiod. London: H. Lownes for Miles Partrich, 1618.

- The Crowne of all Homers Workes: Batrachomyomachia; or, The battaile of frogs and mise; His Hymn's and Epigrams. London: Eliot's Court Press for John Bill, [1624?]

- Chapman's Homer: 'The Iliad', 'The Odyssey', and the lesser Homerica (edited by Allardyce Nicoll). (2 volumes), New York: Pantheon, 1956.

- George Chapman's Minor Translations (edited by Richard Corballis). Salzburg, Austria: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 1984.

Collected editions

- Works. (3 volumes), London: Chatto & Windus, 1874-1875

- Volume I: Plays (edited by Richard Herne Shepherd). 1874.

- Volume II: Homer's 'Iliad' and Odyssey' (edited by Richard Herne Shepherd). 1874.

- Volume III: Poems and Minor Translations (with introduction by Algernon Charles Swinburne). 1875.

- Plays and Poems (edited by Thomas Marc Parrott). (2 volumes), London: Routledge / New York: Dutton, 1910-1914. Volume 1: The Tragedies, Volume 2: The Comedies

- "The Divine Poem of Musæus" (translated by Chapman) and "Hero and Leander" (completed by Chapman) in Elizabethan Minor Epics (edited by Elizabeth Story Donno). New York: Columbia University Press, 1963, pp. 70-126.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[14]

See also

'He must obey his fate' from George Chapman, Chabot, Admiral of France (revised 1638)

References

Swinburne, Algernon Charles (1911). "Chapman, George". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 852-854. Wikisource, Web, Dec. 24, 2017.

Notes

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Chapman, George," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 79. Web, Dec. 24, 2017.

- ↑ Athen. Oxon. ii. 575.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Swinburne, 852,

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 Swinburne, 853.

- ↑ Raumer, Briefe aus Paris, 1831, ii. 276.

- ↑ Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds., The New Intellectuals: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1977; pp. 155-60.

- ↑ Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The Popular School: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1975; pp. 151-7.

- ↑ from Andrew Lang, "Critical Introduction: George Chapman (1559?–1634)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Apr. 8, 2016.

- ↑ Quoted on current UK imprint of Flashman novels as cover blurb.

- ↑ A.N.Wilson's review in The Telegraph 15 August 2005

- ↑ Hutchinson, Thomas (undated). The Complete Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley: Including Materials Never Before Printed in any Edition of the Poems & Edited with Textural Notes. E. W. Cole: Commonwealth of Australia; Book Arcade, Melbourne. p. 38. (NB: Hardcover, clothbound, embossed.) Published prior to issuing of ISBN.

- ↑ Wilde, Oscar (2003). "The Portrait of Mr. W.H.". Hesperus Press Limited 4 Rickett Street, London SW6 1RU. P.46. First published 1921.

- ↑ "Bridal Song". Arthur Quiller-Couch, editor, Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919). Bartleby.com, Web, May 4, 2012.

- ↑ George Chapman 1559-1634, Poetry Foundation, Web, Aug. 18, 2012.

External links

- Poems

- "Bridal Song"

- "An Epicede or Funeral Song"

- Chapman, George (1559?-1634) (4 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- George Chapman 1559-1634 at the Poetry Foundation

- Chapman in The English Poets: An anthology: The Thames (from Ovid's Banquet of Sense, The Spirit of Homer (from The Tears of Peace), "The Procession of Time," Helen on the Rampart (from Iliad III, The Camp at Night (from Iliad VIII, The Grief of Achilles for the Slaying of Patroclus, Menoetius’ Son (from Iliad XVIII), Hermes in Calypso’s Island (from Odyssey V), Odysseus’ Speech to Nausicaa (from Odyssey VI), The Song the Sirens Sung (from Odyssey XII), Odysseus Reveals Himself to His Father (from Odyssey XXIV)

- George Chapman at PoemHunter (15 poems)

- George Chapman at Poetry Nook (244 poems)

- Quotes

- Bartlett's Chapman quotations

- George Chapman at Wikiquote

- Books

- Five Chapman Plays Online.

- Works by George Chapman at Project Gutenberg

- George Chapman at the Online Books Page

- George Chapman at Bartleby.com

- Audio / video

- George Chapman poems at YouTube

- Books

- Works by George Chapman at Project Gutenberg

- George Chapman at Amazon.com

- About

- George Chapman in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- George Chapman at Imagi-nation

- George Chapman at Elizabethan Authors

- Chapman, George (1559-1634)] in the Dictionary of National Biography

- George Chapman at English Poetry, 1579-1830.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at "Chapman, George"

|