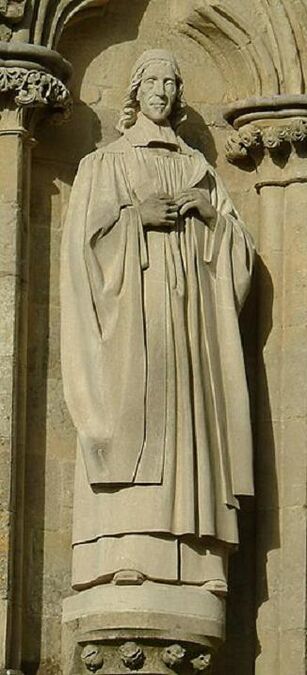

Statue of George Herbert (1593-1633) at Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, UK. Photo by Richard Avery. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| George Herbert | |

|---|---|

| Born |

April 3 1593 Montgomery, Powys, Wales |

| Died |

March 1 1633 (aged 39) Bemerton, Wiltshire, England |

| Occupation | Poet, priest |

Rev. George Herbert (3 April 1593 - 1 March 1633) was a Welsh-born English poet, orator, and Anglican priest.

Life[]

Overview[]

Herbert was educated at Westminster School and Cambridge, where he took his degree in 1616, and was public orator 1619-1627. He became the friend of Sir H. Wotton, Donne, and Bacon, the last of whom is said to have held him in such high esteem as to submit his writings to him before publication. He acquired the favor of James I, who conferred upon him a sinecure worth £120 a year, and having powerful friends, he attached himself for some time to the Court in the hope of preferment. The death of 2 of his patrons, however, led him to change his views, and coming under the influence of Nicholas Ferrar, the quietist of Little Gidding, and of Laud, he took orders in 1626 and, after serving for a few years as prebendary of Layton Ecclesia, or Leighton Broomswold, he became in 1630 rector of Bemerton, Wilts, where he passed the remainder of his life, discharging the duties of a parish priest with conscientious assiduity. His health, however, failed, and he died in his 40th year. His chief works are The Temple; or, Sacred poems and private ejaculations (1634), The Country Parson (1652), and Jacula Prudentium, a collection of pithy proverbial sayings, the 2 last in prose. Not published until the year after his death, The Temple had immediate acceptance, 20,000 copies (according to I. Walton, who was Herbet's biographer) having been sold in a few years. Among its admirers were Charles I, Cowper, and Coleridge. Herbert wrote some of the most exquisite sacred poetry in the language, although his style, influenced by Donne, is at times characterised by artificiality and conceits. He was an excellent classical scholar, and an accomplished musician.[1]

Herbert wrote religious poems characterized by a precision of language, a metrical versatility, and an ingenious use of imagery or conceits in the style of the metaphysical school of poets.[2] Charles Cotton described him as a "soul composed of harmonies".[3] Herbert himself, in a letter to Nicholas Ferrar said of his writings, "they are a picture of spiritual conflicts between God and my soul before I could subject my will to Jesus, my Master".[4] Some of Herbert's poems have endured as hymns, including "King of Glory, King of Peace" (Praise), "Let All the World in Every Corner Sing" (Antiphon) and "Teach me, my God and King" (The Elixir).[5] A distant relative is Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert.[6]

Family[]

Herbert was the 4th son of Sir Richard Herbert by his wife Magdalen, and the brother of Edward, lord Herbert of Cherbury .[7]

His great-great-grandfather was Sir Richard Herbert of Colebrooke, Devonshire, the brother of William Herbert, earl of Pembroke (died 1469). His great-grandfather, Sir Richard Herbert, was active in repressing disturbances about Montgomery Castle in the reign of Henry VIII (Herbert, Henri VIII, sub anno 1520).[8]

His grandfather, Sir Edward Herbert, took part under his kinsman, William Herbert, earl of Pembroke (1501?-1570), in the storming of St. Quentin in 1557; repressed lawlessness in Wales with a strong hand as deputy-constable of Aberystwith Castle (16 March 1543-4) and as sheriff of Montgomeryshire (1557 and 1568); was M.P. for his county in 1553 and 1556-7; was esquire of the body to Queen Elizabeth, and was buried in Montgomery Church 20 May 1593.[8]

George's father was sheriff of Montgomeryshire in 1576 and 1584, and is probably the Richard Herbert who sat as M.P. for Montgomeryshire in the parliament of 1585-6. He died in 1596, and was buried in the Lymore chancel of Montgomery Church on 15 October of that year.[8]

Herbert's mother was Magdalen, daughter of Sir Richard Newport (died 1570) and Margaret, daughter and heiress of Sir Thomas Bromley (died 1555?). Magdalen was a woman of great personal charm and fervent piety, and deeply interested herself in the education of her 7 sons and 3 daughters. While at Oxford with her eldest son Edward she made the acquaintance of poet John Donne, with whom she maintained for the remainder of her life "an amity made up of a chain of suitable inclinations and virtues" (Walton, Life of George Herbert). She was liberal in her gifts to Donne's family; he addressed much of his sacred poetry to her, and commemorated her noble character in sonnets, and in a touching poem called "The Autumnal Beauty." In 1608 she married, at the age of 40, a 2nd husband, Sir John Danvers, nearly 20 years her junior. The union was, according to Donne, thoroughly happy, and Sir John treated all his step-children with the utmost kindness (cf. Hist. MSS. Comm. 10th Rep. pt. iv. 379). She died in June 1627, and was buried in the parish church of Chelsea, near her 2nd husband's London residence. A sermon on her life and character was preached by Donne on 1 July following, and was published, together with commemorative verses by George Herbert. Her manuscript household book, with the expenses of her house in London between April and September 1601, belonged to Heber (Cat. pt. xi. p. 829).[8]

Youth and education[]

George Herbert was born at Montgomery Castle on 3 April 1593.[7]

As a child he was educated at home under the care of his mother, whose virtues he commemorated in verse, and he may have accompanied her in 1598 to Oxford, where she went for 4 years to keep house for her eldest son, Edward.[7]

In his 12th year (1604-1605) George was sent to Westminster School, and obtained there a king's scholarship on 5 May 1609. He matriculated from Trinity College, Cambridge, on 18 December 1609, earning a B.A. in 1612-1613, and an M.A. in 1616.[7]

The master of the college, Dean Neville, recognized Herbert's promise, and he was elected a minor fellow on 3 October 1614, major fellow 15 March 1615-16, and sublector quartæ classis 2 October 1617.[7]

Academic career[]

Herbert was now a finished classical scholar. Throughout his life he was a good musician, not only singing, but playing on the lute and viol. His accomplishments soon secured for him a high position in academic society, and he attracted the notice of Lancelot Andrewes, bishop of Winchester. Herbert contributed 2 Latin poems to the Cambridge collection of elegies on Prince Henry (1612), and 1 to that on Queen Anne (1619).[7]

At an early period of his university career he wrote a series of satiric Latin verses in reply to Andrew Melville's Anti-Tami-Cami-Categoria (1st published in 1604). Melville's work was an attack on the universities of Oxford and Cambridge for passing resolutions hostile to the puritans at the beginning of James I's reign. Herbert's answer cleverly defended the established church at all points, and he declared himself strongly opposed to puritanism, an attitude which he maintained through life. Loyal addresses to James I and Charles, prince of Wales, were prefixed, but this work, although circulated in manuscript while Herbert was at Cambridge, was not printed till nearly 30 years after his death, when James Duport, dean of Peterborough, prepared it for publication (1662).[7]

In 1618 Herbert was prelector in the rhetoric school at Cambridge, and on an occasion lectured on an oration recently delivered by James I, bestowing on it extravagant commendation (Hacket, Life of Williams, i. 175; cf. D'Ewes, Diary, i. 121). Despite his preferments, his income was small, and he was unable to satisfy his taste for book-buying. When appealing for money to his stepfather, Sir John Danvers (17 March 1617-18), he announced that he was "setting foot into divinity to lay the foundation of my future life," and that he required many new books for the purpose.[7]

Soon afterwards he left his divinity studies to become a candidate for the public oratorship at Cambridge — "the finest place [he declared] in the university." He energetically solicited the influence of Sir Francis Nethersole, the retiring orator, of his stepfather, of his kinsman, the Earl of Pembroke, and of Sir Benjamin Rudyerd. His suit proved successful, and on 21 October 1619 he was appointed deputy orator. On 18 Jan. 1618-19 Nethersole finally retired, and Herbert was formally installed in his place.[7]

His duties brought him into relations with the court and the king's ministers. He wrote on behalf of the university all official letters to the government, and the congratulations which he addressed to Buckingham in 1619 on his elevation to the marquisate, and to Thomas Coventry on his appointment as attorney-general in 1620, prove that he easily adopted the style of a professional courtier. He frequently attended James I as the university's representative at Newmarket or Rovston,and he sent an effusively loyal letter of thanks to the king (20 May 1620) in acknowledgment of the gift to the university of a copy of the Basilikon Doron. The flattery delighted the king.[7]

Courtier[]

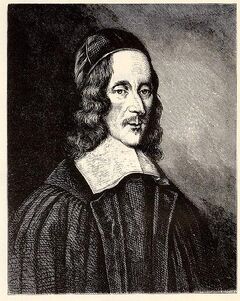

Herbert by Robert White (1645-1703), 1674. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Herbert thenceforth was constantly at court, and received marks of favor from Lodowick, duke of Lennox, and James, marquis of Hamilton.[7] He made the personal acquaintance of Bacon, the lord chancellor. As orator he had thanked Bacon for a gift to the university of his Instauratio (4 Nov. 1620), and had written complimentary Latin verses on it in his private capacity. Bacon dedicated to Herbert his "translation of certaine psalms" (1625), "in recognition of the pains that it pleased you to take about some of my writings."[9]

In 1623 Herbert delivered an oration at Cambridge congratulating Prince Charles on his return from Spain, and he expressed regret, in the interests of peace, that the Spanish match had been abandoned. Herbert at the time undoubtedly hoped to follow the example of Sir Robert Naunton and Sir Francis Nethersole, his predecessors in the office of orator, and obtain high preferment in the service of the state. But the death, in 1625, of the king and of 2 of his chief patrons, and his suspicions of the wisdom of Buckingham's policy, led him to reconsider his position.[9]

Church career[]

Herbert's own early inclinations were towards the church, and his mother had often urged him to take holy orders. To resolve his doubts whether to pursue "the painted pleasures of a court life, or betake himself to a study of divinity," he withdrew to a friend's house in Kent, and studied with such energy as to injure his health.[9]

While still undecided, Herbert was presented to the prebend of Laygon Ecclesia by John Williams, bishop of Lincoln, presented him to the prebend of Layton Ecclesia. To the prebend was attached an estate at Leighton Bromswold, Huntingdonshire, on which stood a dilapidated church. Herbert was not ordained, and was thus unable to perform the duties connected with the benefice; but the presentation called into new life the religious ardor of his youth.[9]

2 miles from Leighton was Little Gidding, the home of Nicholas Ferrar, with whom Herbert had some slight acquaintance while both were students at Cambridge. Herbert offered to transfer the prebend to Ferrar; but Ferrar declined the offer, and urged Herbert to set to work to restore the ruined church (Ferrar, Life of Nicholas Ferrar, ed. Mayor, 49-50). Herbert eagerly followed Ferrar's advice. £2,000 were needed. His own resources were unequal to that demand, but with the help of friends he carried the work through.[9]

With Ferrar, who gave money as well as advice, Herbert corresponded from then on in terms of great intimacy. They styled each other "most entire" friends and brothers, but they seem only to have met once in later years. Herbert's final absorption in a religious life was doubtless largely due to Ferrar's guidance.[9]

Donne, the friend of Herbert's mother, proved also a sympathetic friend, especially at the time of Lady Danvers's death in 1627. To Herbert, Donne gave 1 of his well-known seals, bearing on it a crucifix shaped like an anchor.[9]

Owing partly to ill-health, and partly to his attendance at court, Herbert had already delegated his duties as orator at Cambridge to a deputy, Herbert Thorndike, and at the close of 1627 he resigned the post altogether.[9]

Threatened with tuberculosis, he spent the year 1628 at the house of his brother, Sir Henry Herbert, at Woodford, Essex, and early in 1629 visited the Earl of Danby, brother of his stepfather, at Dauntsey, Wiltshire. There he met, and fell in love with, a relative of his host, Jane Danvers, whose father, Charles Danvers of Baynton, Wiltshire, lately dead, had formed a high opinion of Herbert's character, and openly told him that he wished him to marry a daughter of his. The marriage took place at Edington on 5 March 1628-9.[9]

In 6 April 1630, Charles I, at the request of the earl of Pembroke, presented Herbert to the rectory of Fugglestone with Bemerton, Wiltshire. He was in doubt whether or not to accept the presentation, but went to Wilton to thank the earl for his kind offices. Laud, bishop of London, was then with the king at Salisbury, and Pembroke immediately informed him of Herbert's hesitation. Laud sent for Herbert, and convinced him that it was sinful to refuse the benefice. Tailors were summoned to supply clerical vestments, and Herbert was instituted to the rectory by John Davenant, bishop of Salisbury, on 26 April 1630.[9]

Herbert's life at Bemerton was characterized by a saint-like devotion to the duties of his office. There he wrote his far-famed series of sacred poems. He still practiced music in his leisure, and twice a week he walked to Salisbury Cathedral. He repaired Bemerton Church (thoroughly restored by Wyatt in 1866), and rebuilt the parsonage, inscribing on the latter some verses addressed to his successor. Friends contributed to these expenses, but he spent (he wrote to his brother Henry) 200l. from his own resources, "which to me that have nothing yet is very much."[9]

But tuberculosis soon declared itself, and after an incumbency of less than 3 years he was buried beneath the altar of his church on 3 March 1632-3. He had no children, and left all his property to his wife, saving a few legacies of money and books to friends.[9]

His widow afterwards married Sir Robert Cook of Highnam House, Gloucestershire, whither she carried many of Herbert's writings. These were burnt with the house by the parliamentary forces during the civil war.[9] A library of books which Herbert had deposited, with chains affixed to the volumes, in a room in Montgomery Castle, met with a very similar fate (Powysland Club Coll. vii. 132). Herbert's widow was buried at Highnam in 1656 (Notes and Queries, 1st ser. ii. 157).[10]

Writing[]

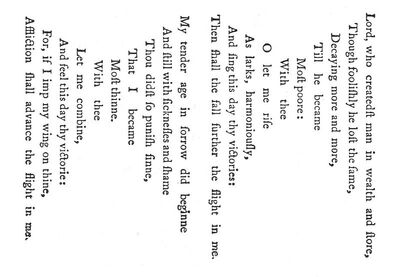

Herbert's "Easter Wings", a pattern poem in which the work is not only meant to be read, but its shape is meant to be appreciated: In this case, the poem was printed (original image here shown) on 2 pages of a book, sideways, so that the lines suggest 2 birds flying upward, with wings spread out.

The Temple[]

On his deathbed Herbert directed a little manuscript volume of verse to be delivered to his friend Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding, with a view to publication. Ferrar at once applied for a license to the vice-chancellor of Cambridge University, who hesitated, on the ground that 2 lines in a poem ("The Church Militant") alluded somewhat contemptuously to the emigration of religion from England to America. But the prohibition was soon withdrawn.[10]

The volume was entitled The Temple: Sacred poems, and private ejaculations, and Ferrar, the editor, described in a preface Herbert's piety. Except the opening and closing poems, entitled respectively "The Church Porch" and "The Church Militant," almost all the pieces are very brief.[10]

The earliest edition, which probably appeared within 3 weeks of Herbert's death, bears no date on the title-page. It was apparently printed for private circulation only. A unique copy of it is in the Huth Library. The 1st edition issued to the public bears the date 1633. A 2nd edition was issued in the same year, and later editions are dated 1634, 1635, 1638, 1641, 1656, 1660, 1667, 1674, 1679, 1703, and 1709. All editions earlier than 1650 were printed and published at Cambridge. Izaak Walton, writing in 1670, says that more than 20,000 copies had been "sold since the first impression."[10]

"The Synagogue" of Christopher Harvey, which is printed in all the later editions, was originally appended to that of 1641. A portrait of Herbert, engraved by R. White, was introduced into the 1674 edition, with which Walton's life was also reprinted. The text of the 1679 edition is disfigured by misprints, which have been repeated in many later editions. An alphabetical table was first added in 1709. Modern reprints are very numerous. An attractive edition, issued by Pickering, is dated 1846. Mr. J.H. Shorthouse wrote a preface for a facsimile reproduction in 1882. But the fullest edition of Herbert's poems is that edited by Dr. Grosart in vols. i. and ii. of his collected edition of Herbert's works (1874), and reproduced in the Aldine series in 1876.[10]

A manuscript copy (fol.) of the Temple, which seems to have been presented by Ferrar to the vice-chancellor of Cambridge for his license in March 1632-3, is in the Bodleian Library. A manuscript volume containing portions of the Temple, with a few other English poems by Herbert which are not included in Ferrar's edition, and 2 collections of Latin epigrams, entitled respectively Passio Discerpta and Lucus, is in Dr. Williams's Library, Gordon Square, London. It seems to have belonged to Ferrar, and to have been bound by him at Little Gidding. The English verses may possibly represent an early plan of the Temple. Dr. Grosart, in his complete edition of Herbert's poems, has carefully collated the text of the printed with the manuscript versions, and has published all the additional poems, both English and Latin, which are found in the Dr. Williams's MS.[10]

Herbert's poems found much favor with his seriously-minded contemporaries. Richard Crashaw, in presenting the Temple "to a Gentlewoman," speaks enthusiastically of Herbert's "devotions" and expositions of "divinest love." Walton, who in his ‘Angler’ quotes 2 of his poems, "Virtue" and "Contemplation of God's Providence," characterises the Temple, in his life of Donne, as "a book in which, by declaring his own spiritual conflicts, he hath comforted and raised many a dejected and discomposed soul and charmed them with sweet and quiet thoughts." Richard Baxte found, "next the scripture poems," "none so savoury" as Herbert's, who "speaks to God like a man that really believeth in God" (Poetical Fragments, pref. 1681). Henry Vaughan, in the preface to his Silex Scintilians, 1650, credits Herbert with checking by his holy life and verse "the foul and overflowing stream" of amatory poetry which flourished in his day.[10]

Charles I read the Temple while in prison. Archbishop Leighton carefully annotated his copy with appreciative manuscript notes. Cowper's religious melancholy was best alleviated by poring over the book all day long. Coleridge wrote of the weight, number, and compression of Herbert's thoughts, and the simple dignity of the language (Biog. Lit.)[10]

But in spite of these testimonies Herbert's verse, from a purely literary point of view, merits on the whole no lofty praise. His sincere piety and devotional fervour are undeniable, and in portraying his spiritual conflicts and his attainment of a settled faith he makes no undue parade of doctrinal theology. But his range of subject is very narrow. He was at all times a careful literary workman, and the extant manuscript versions show that he was continually altering his poems with a view to satisfying a punctilious regard for form. An obvious artificiality is too often the result of his pains.[10]

He came under Donne's influence, and imitated Donne's least admirable conceits. Addison justly censured his "false wit" (Spectator, No. 58). In 2 poems, "Easter Wings" and "The Altar," he arranges his lines so as to present their subjects pictorially. But on very rare occasions, as in his best-known poem, that on "Virtue," beginning "Sweet day so cool, so calm, so bright,’ or in that entitled "The Pulley," he shows full mastery of his art, and, despite some characteristic blemishes, writes as though he were genuinely inspired.[10]

Miscellaneous[]

Besides the Latin poems contributed to the Cambridge collections, Herbert only published in his lifetime Parentalia, verses in Latin and Greek to his mother's memory, which were appended to Donne's funeral sermon (London, 1627,12mo), and Oratioquâ auspicatissimum Serenissimi Principis Caroli Reditum ex Hispanijs celebrauit Georgius Herbert, Academiæ Cantabrigiensis Orator, printed by Cantrell Legge at the Cambridge University Press, 1623. All the poetic work by which he is remembered was published posthumously.[10]

Herbert is also credited with verse-renderings of 8 psalms, which are signed G.H., in John Playford's Psalms and Hymns,’ London, 1671, fol. Walton, in his Life of Herbert, prints 2 sonnets addressed by him to his mother. Aubrey quotes inscriptions assigned to Herbert on the tomb of Lord Dunvers at Dauntsey, and on the picture of Sir John Danvers, his stepfather's father. A poem by Herbert called A Paradox in the Rawlinson MSS. at the Bodleian Library, and a poetic address to the queen of Bohemia in Brit. Mus. Harl. MS. 3910, pp. 121-2, were 1st printed by Dr. Grosart. In 1662 Herbert's reply to Andrew Melville's Anti-Tami-Cami-Categoria of 1604 was published at Cambridge as an appendix to a volume entitled Ecclesiastes Solomonis. Auctore Joan. Viviano. Canticum Solomonis: Nec non Epigrammata per Ja. Duportum. Herbert's verses appear with a separate titlepage: "Georgii Herberti Angli Musæ Responsoriæ ad Andreæ Melvini Scoti, Anti-Tami-Cami-Categoriam."[10]

Herbert's chief work in prose is A Priest to the Temple; or, The countrey parson: His character and rule of holy life, which was 1st issued in a little volume (London 1652, 12mo) bearing the general title Herbert's Remains, and including a 2nd tract called Jacula Prudentum. A brief address to the reader, signed by Herbert, is dated 1632, and there is a biographical notice of the author by Barnabas Oley. The 2nd edition (Lond. 1671, 12mo) contains a new preface by Oley, which deals only with the theological value of the volume.[10] The book is a record of the duties and aspirations of a pious country clergyman, but the style is marred by affectations and wants simplicity.[11]

Herbert also added to his friend Ferrar's English translation of Leonard Lessius's Hygiasticon a translation from the Latin of Cornaro entitled "A Treatise of Temperance and Sobrietie," and made at the request "of a noble personage." This was first published at the Cambridge University Press in 1634. With Ferrer's translation of Valdezzo's ‘Hundred and Ten Considerations … of those things … most perfect in our Christian profession’ (Oxford, 1638) were published a letter from Herbert to Ferrar on his work, and "Briefe Notes [by Herbert] relating to the dubious and offensive places in the following considerations." The licenser of the press in his imprimatur calls special attention to Herbert's notes. In the 1646 edition of Ferrar's Valdezzo Herbert's notes are much altered.[11]

In 1640 there appeared in Witt's Recreations a little tract entitled "Outlandish Proverbs selected by Mr. G.H." — a collection of 1,010 proverbs. This tract was republished with many additions and alterations as Jacula Prudentum; or, Outlandish proverbs, sentences, &c.; selected by Mr. George Herbert, late Orator of the Universitie of Cambridge, in 1651, and with it were printed "The Author's Prayers before and after Sermons" (which also appear in Herbert's Country Parson); his letter to Ferrar "upon the translation of Valdesso" (dated from Bemerton, 29 Sept. 1632); and Latin verses on Bacon's Instanratio Magna,’ on Bacon's death, and on Donne's seal. The volume concludes with An Addition of Apothegmes by Severall Authours. This book was reissued in 1652 as a 2nd part of the volume entitled Herbert's Remains (London 12mo).[11]

4 affectionate letters to his younger brother, Sir Henry Herbert, dated 1618 and later, appear in Warner's Epistolary Curiosities, 1818, 1-10. His letters to Ferrar are inserted in Webb's Life of Ferrar; his letters to his mother were printed by Walton, and some official letters from Cambridge as orator are extant in the university archives.[11]

Critical introduction[]

The Temple is the enigmatical history of a difficult resignation; it is full of the author’s baffled ambition and his distress, now at the want of a sphere for his energies, now at the fluctuations of spirit, the ebb and flow of intellectual activity, natural to a temperament as frail as it was eager. There is something a little feverish and disproportioned in his passionate heart-searchings.

The facts of the case lie in a nutshell. Herbert was a younger son of a large family; he lost his father early, and his mother, a devout, tender, imperious woman, decided, partly out of piety and partly out of distrust of his power to make his own way in the world, that he should be provided for in the Church. When he was 26 he was appointed Public Orator at Cambridge, and hoped to make this position a stepping-stone to employment at court. After 8 years his patrons and his mother were dead, and he made up his mind to settle down with a wife on the living of Bemerton, where he died after a short but memorable incumbency of 3 years. The flower of his poetry seems to belong to the two years of acute crisis which preceded his installation at Bemerton or to the Indian summer of content when he imagined that his failure as a courtier was a prelude to his success in the higher character of a country parson.

The well-known poem on Sunday, which he sang to his lute so near the end, and the quaint poem on the ideal priest, may date from Bemerton. "The Quip" and "The Collar" may date from the years of crisis. Still, much, like the poems on "Employment," dates from the years of hopeful ambition. There are no traces of consecration or defeat in the "Church Porch," where Herbert, like a precocious Polonius, frames a rule of life for himself and other pious courtiers. Herbert, who had thought much of national destiny, and decided that religion and true prosperity were to take flight for America, considered that England was "full of sin, but most of sloth."

The plain truth is, that after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the submission of the chieftains of Ulster, and the tardy pacification of the Netherlands, the English gentry were for the first time since the Field of the Cloth of Gold without a rational object of public concern. Poets were left for the first time to feed idly on their own fancies and feelings: that all kinds of enterprise were feasible, as Herbert repeatedly urged, was of little avail in the absence of motive power. The excitement without impulse which characterises Herbert is the explanation of the old criticism that he has ‘enthusiasm without sublimity.’ He was, it may be, too fastidious to have succeeded in the best of times. The ascetic temper shows early —

- ‘Look on meat, think it dirt, then eat a bit,

- And say withal—“earth to earth I commit”;’

and more pleasantly —

‘Welcome dear feast of Lent. Who loves not thee

He loves not temperance or authority.

- * * * *

Beside the cleanness of sweet abstinence

Quick thoughts and motions at a small expense,

A face not fearing light.’

He thinks thrift and cleanness go well together, and likes strictness and method for their own sake. The worldling’s false pride in licence offends him from the beginning. There is more self-complacency than penitence in a poem like "The Size." From the 1st he is preoccupied with the thought of death, and hungers for eternity. Only at 1st the feeling is that he holds of God for 2 lives, and hopes to make improvement in both: it is affliction that convinces him that he must sacrifice everything in the present life.

To the last his piety lacks wings: he is always tormenting himself that he does not love as he should; his fastidious imagination cannot stop short of the highest good, and then he finds that the imagination cannot carry the affections with it in its flight. He tries vainly to chide and argue himself into fervour: when the mood of fanciful exaltation becomes unattainable he trembles under a sense of deserved displeasure: he feels the pathos of his own ingratitude more keenly than he feels the majesty or the generosity of the Being he is trying to love. He is far too ingenious for the contagious passion of the great mystics: he moves us most when he subsides into meek wistful yearning, and then he is more interesting for himself than for his subject.[12]

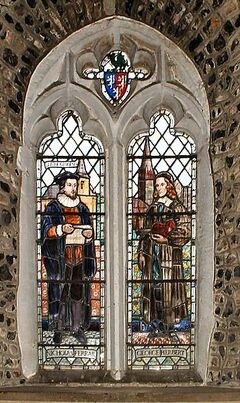

Nicholas Ferrar (l) and George Herbert, Church of St. Andrew, Bemerton. Photo by Weglinde, 2008. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Recognition[]

A memorial window commemorating Herbert and William Cowper is in St. George's Chapel, Westminster Abbey.[13]

Herbert has a statue in niche 188 on the West Front of Salisbury Cathedral.

He is commemorated on 27 February throughout the Anglican Communion and on 1 March of the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

6 of his poems ("Virtue", "Easter", "Discipline", "A Dialogue," "The Pulley," and "Love") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[14]

His poetry has been set to music by several composers, including Ralph Vaughan Williams, Lennox Berkeley, Benjamin Britten, Judith Weir, Randall Thompson, William Walton and Patrick Larley.

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Temple: Sacred poems and private ejaculations (edited by Nicholas Ferrar). Cambridge, UK: Thomas Buck & Roger Daniel, 1633;

- (edited by Francis Meynell). London: Nonesuch Press, 1927.

- Poetical Works (edited by George Gilfillan). Edinburgh: James Nichol, 1853; New York: Appleton, 1854.

- Poetical Works (edited by Alexander Balloch Grosart). London: George Bell, 1886.

- Poems (with introduction by Arthur Waugh). London: Oxford University Press, 1907.

- Latin Poetry (translated by Mark McCloskey & Paul R. Murphy). Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1965.

- Selected Poetry (edited by Joseph H. Summers). New York: New American Library, 1967.

- Major Poets of the Earlier Seventeenth Century (edited by Barbara K. Lewalski and Andrew J. Sabol). New York: Odyssey Press, 1973.[15]

- English Poems (edited by C.A. Patrides). London: Dent / Totowa, NJ: Rowan & Littlefield, 1974.

- The Williams Manuscript of George Herbert's Poems (edited by Amy M. Charles). Delmar, NY: Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1977.

- George Herbert and Henry Vaughan (edited by Louis Lohr Martz). Oxford, UK, & New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Selected Poems (edited by Jo Shapcott). London: Faber (Poet to Poet), 2006.

Non-fiction[]

- Oratio Qua auspicatissimum Serenissimi Principis Caroli. Cambridge, UK: 1623.

- Memoriae Matris Sacrum, printed with A Sermon of commemoracion of the ladye Danvers by John Donne ... with other Commemoracions of her by George Herbert. London: Philemon Stephens & Christopher Meredith, 1627.[15]

- A Priest to the Temple; or, The country parson, his character, and rule of holy life. London: T.R. for Benj. Tooke, 1675;

- A Priest to the Temple. New York: Thomas Whittaker, 1908.[16]

Collected editions[]

- Herbert's Remains; Or, Sundry pieces of that sweet singer of the Temple (edited by Barnabas Oley). London: Timothy Garthwait, 1652.[15]; London: William Pickering, 1845; Menston, UK: Scolar Press, 1970.

- Works in Prose and Verse (edited by William Pickering). (2 volumes), London: W. Pickering, 1841. Volume 2.

- Complete Works in Verse and Prose (edited by Alexander B. Grosart). (3 volumes), London: privately published, printed by Robson & Sons, 1874.

- English Poems: Together with his collection of proverbs entitled Jacula Prudentum. London: Rivingtons, 1877.

- English Works (edited by George Herbert Palmer). (3 volumes), Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1905; London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1905. Volume I, Volume II,Volume III

- The Temple / A Priest to the Temple. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1908.

- Works (edited by F.E. Hutchinson). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1941; revised, 1945.

Edited[]

Jacula Prudentum; or, Outlandish proverbs, sentences, &c. in Witt's Recreations, 1640;[11]

- revised & expanded, London: T.M., for T. Garthwait, 1651.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[17]

Selection from 'The Temple' by George Herbert (FULL Audiobook)

See also[]

The Collar by George Herbert

George Herbert - Virtue - poem

References[]

Lee, Sidney (1891) "Herbert, George (1593-1633)" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 26 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 185-188. Wikisource, Web, Jan. 25, 2018.

- Falloon Jane, Heart in Pilgrimage: A study of George Herbert,Author House, Milton Keynes 2007 ISBN 978-1-4259-7755-9

- Lewis-Anthony Justin, If you meet George Herbert on the road, kill him: Radically re-thinking priestly ministry, an exploration of the life of George Herbert as a take-off for a re-evaluation of the ministry within the Church of England. August 2009.

- Sheldrake, Philip (2009) Heaven in Ordinary: George Herbert and his writings. Canterbury Press ISBN 978-1-85311-948-4

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Herbert, George," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 188. Web, Jan. 24, 2018.

- ↑ The Grolier 1996 Multimedia Encyclopedia, Grolier Electronic Publishing, Inc.

- ↑ Schmidt Michael, Poets on Poets, (Essay on George Herbert), Carcanet Press, Manchester, 1997 ISBN 1-85754-339-4

- ↑ Maycock A.L., Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding,SPCK,London 1938

- ↑ The Baptist Hymn Book,Poems and Hymn Trust,London 1962

- ↑ "The New York Times". 29 July 1998. The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950CE3DF1438F93AA15754C0A96E958260. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Lee, 185.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3

Lee, Sidney (1891) "Herbert, Edward (1583-1648)" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 26 London: Smith, Elder, p. 173. Wikisource, Web, May 22, 2022.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Lee, 186.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 Lee, 187.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Lee, 188.

- ↑ from George Augustus Simcox, "Critical Introduction: Sandys, Herbert, Crashaw, Vaughan," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Feb. 10, 2016.

- ↑ George Herbert, People, History, Westminster Abbey. Web, July 11, 2016.

- ↑ George Herbert in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 18, 2012.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 George Herbert 1593-1633, Poetry Foundation, Web, Oct. 3, 2012.

- ↑ A Priest to the Temple, Internet Archive. Web, Jan. 29, 2013.

- ↑ Search results = au:George Herbert, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Feb. 10, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Christmas"

- Herbert in the Oxford Book of English Verse: "Virtue," "Easter," "Discipline," "A Dialogue," "The Pulley," "Love"

- Herbert in the Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse: "Affliction," "Man," "Clasping," "The Elixer," "The Collar"

- George Herbert biography & 4 poems at the Academy of American Poets

- George Herbert 1593–1633 at the Poetry Foundation

- Herbert in The English Poets: An anthology: "The Collar," "Aaron," "The Quip," "Misery," "Love," "The Pulley," "Employment," "The World"

- Herbert, George (21 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- George Herbert at Poetry Nook (68 poems)

- George Herbert at PoemHunter (85 poems)

- George Herbert poems at PoetSeers

- Examples of George Herbert's poetic forms

- Books

- George Herbert at Amazon.com

- About

- George Herbert in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- George Herbert at NNDB

- George Herbert, priest and poet at Anglican.org.

- George Herbert at the Cambridge Authors Project

- George Herbert (1593-1633) at Luminarium

- GeorgeHerbert.org Official website.

- George Herbert and Bemerton, about his priesthood and parish

- The Life of Mr. George Herbert by Izaak Walton (1593-1683)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Herbert, George (1593-1633)

|