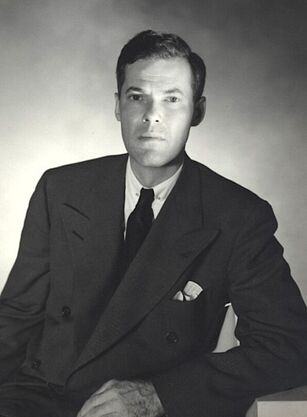

Glenway Wescott (1901-1987). Courtesy Pinterest.

| Glenway Wescott | |

|---|---|

| Born |

April 11, 1901 Kewaskum, Wisconsin |

| Died |

February 22, 1987 (aged 85) Rosemont, New Jersey |

| Occupation | Writer |

Glenway Wescott (April 11, 1901 - February 22, 1987) was an American poet and novelist, and a figure in the American expatriate literary community in Paris during the 1920s.

Life[]

Wescott was born on a farm in Kewaskum, Wisconsin in 1901. He studied at the University of Chicago, where he was a member of a literary circle that included Elizabeth Madox Roberts, Yvor Winters, and Janet Lewis. Independently wealthy, he began his writing career as a poet, but is best known for his short stories and novels, notably The Grandmothers (1927).

Wescott was gay.[1] His relationship with longtime companion Monroe Wheeler lasted from 1919 until Wescott's death.

Wescott lived in Germany (1921–22), and in France (circa 1925–33), where he mixed with Gertrude Stein and other members of the Lost Generation. In the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), Stein wrote about him: "There was also Glenway Wescott but Glenway Wescott at no time interested Gertrude Stein. He has a certain syrup but it does not pour."

Ernest Hemingway sneered of Wescott's debut novel, The Grandmothers, that "every sentence was designed to make Glenway Wescott immortal." Hemingway also complained to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, that Wescott, Thornton Wilder, and Julian Green (all gay) were getting rich, while he had "wives and children to support." However, Hemingway's antipathy to Wescott may not have been simply due to homophobia: there is a story that Hemingway's mother once told him he should write more like Wescott.[2]

Wescott and Wheeler returned to the United States and maintained an apartment in Manhattan with photographer George Platt Lynes. When in 1936 his brother Lloyd moved to a dairy farm in Union township (near Clinton) in Hunterdon co., New Jersey, in 1936, Wescott (along with Wheeler and Lynes moved into a farmhand house, which they named Stone-Blossom.[3]

In 1959, when his brother Lloyd acquired a farm near the village of Rosemont in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, Wescott moved into a 2-story stone house on the property, dubbed Haymeadows.[3]

He died of a stroke at his home in Rosemont.[4]

Writing[]

Allen Ellenzweig: "Wescott (1901-1987) remains a problematic writer for our times, and this is too bad. His language is highly considered in a way foreign to our colloquial age. His sensibility engages emotional restraint at a time when letting it all hang out is de rigueur. He began as a poet, among Yvor Winters and other Imagists like H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) and Mina Loy, and he forever retained an attention to words, one by one, which slowed his facility as a novelist and can give his writing a studied quality. In his new introduction to Wescott’s late journals which he edited, Jerry Rosco, author of the 2002 book Glenway Wescott Personally: A biography, comments that 'his elegant lyrical prose seems more Continental than American' — which I take to mean that while Wescott came from the heartland, his style was more ornate than plain-spoken."[2]

Wescott's novel, The Pilgrim Hawk: A love story (1940), was praised by the critics. Apartment in Athens (1945), the story of a Greek couple in Nazi-occupied Athens who must share their living quarters with a German officer, was a popular success. From then on he ceased to write fiction, although he published essays and edited the works of others. In her essay on The Pilgrim Hawk Ingrid Norton writes, "After...Apartment in Athens, Wescott lived until 1987 without writing another novel: journals (published posthumously as Continual Lessons) and the occasional article, yes, but no more fiction. The Midwest-born author seems to slide into the golden handcuffs of expatriate decadence: supported by the heiress his brother married, surrounded by literate friends, given to social drinking and letter-writing."[5]

Recognition[]

The Grandmothers won the Harper Book Prize in 1927.[6]

In popular culture[]

Wescott was the model for the character Robert Prentiss in Hemingway's novel, The Sun Also Rises. After meeting Prentiss, Hemingway's narrator, Jake Barnes, confesses, "I just thought perhaps I was going to throw up."[1]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Bitterns: A book of twelve poems. Evanston, IL: Monroe Wheeler, 1920.

- Natives of Rock: XX poems, 1921-1922. New York: F. Bianco, 1926.

Novels[]

- The Apple of the Eye. New York: Dial Press, 1924; London: Thornton Butterworth, 1926; New York: Harper, 1926.

- The Grandmothers: A family portrait. New York: Somerset, 1927; New York: Harper, 1927;

- published in UK as A Family Portrait. London: Butterworth, 1927.

- The Babe's Bed. Paris: Harrison, 1930.

- The Pilgrim Hawk: A love story. New York & London: Harper, 1940.

- Apartment in Athens. New York: Harper, 1945;

- published in UK as Household in Athens: A novel. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1945.

Short fiction[]

- ... Like a Lover. Macon, France: Monroe Wheeler, 1926.

- Goodbye, Wisconsin. New York: Harper, 1928; London: Cape, 1929.

- A Visit to Priapus, and other stories (edited by Jerry Rosco). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Non-fiction[]

- Elizabeth Madox Roberts: A personal note. New York: Viking, 1930.

- Fear and Trembling. New York & London: Harper, 1932.

- A Calendar of Saints for Unbelievers. Paris: Harrison, 1932; New York: Harper, 1933.

- Introduction to The Short Novels of Collette. New York: Dial Press, 1951.

- Images of Truth: Remembrances and criticism. New York: Harper, 1962; London: Hamish Hamilton, 1963; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1972.

- When We Were Three: The travel albums of George Platt Lynes, Monroe Wheeler, and Glenway Wescott, 1925-1935 (with Lynes & Wheeler; edited by James Crump & Anatole Pohorilenko). Santa Fe, NM: Arena Editions, 1998.

Journals[]

- Continual Lessons: Journals, 1937-1955 (edited by Robert Phelps & Jerry Rosco). New York: Farrar, Straus, 1990.

- A Heaven of Words: Last journals, 1956-1984 (edited by Jerry Rosco). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[7]

See also[]

THE POET AT NIGHTFALL

References[]

- Daniel Diamond, Delicious: A memoir of Glenway Wescott. Toronto: Sykes Press, 2008..

- Jerry Rosco,Glenway Wescott Personally: A biography. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002.

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Eric Haralson, Henry James and Queer Modernity, Cambridge University Press, 2003, page 175

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Allen Ellenzweig, "[https://glreview.org/article/glenway-wescotts-world/ Glenway Wescott’s World ]," April 14, 2014. Web, Feb. 12, 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rosco, Jerry (2002). Glenway Wescott Personally. University of Wisconsin Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=dZPFVlUjuloC.

- ↑ "Glenway Wescott, 85, Novelist and Essayist". The New York Times, February 24, 1987. Accessed April 4, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.openlettersmonthly.com/year-with-short-novels-love-the-limits-of-narrative-the-pilgrim-hawk/ On The Pilgrim Hawk, Open Letters Monthly by Ingrid Norton

- ↑ Jim Friel, review of Glenway Wescott Personally: A biography by Jerry Rosco, Cercles, 2007. Web, Aug. 15, 2015.

- ↑ Search results = au:Glenway Wescott, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Aug. 15, 2015.

External links[]

- Poems

- Wescott in Poetry: A magazine of verse, 1912-1922: "Ominous Concord," "Without Sleep," "The Chaste Lovers," "To L.S.," "The Poet at Night-fall," "The Hunter"

- Audio / video

- About

- "Gleneway Wescott, 85, novelist and essayist," obituary in the New York Times

- review of Glenway Wescott Personally: A biography by Jerry Rosco at Cercles

- review of A Heaven of Words: Last journals

- The Loves of the Falcon, Edmund White]] essay on Wescott and a review of books by and about him, from The New York Review of Books

- [1] source for DELICIOUS (Diamond)

|