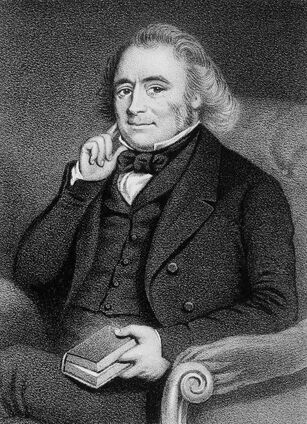

Hartley Coleridge (1796-1849). 1850 engraving by Day & Son, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| Hartley Coleridge | |

|---|---|

| Born |

September 19 1796 Clevedon |

| Died |

June 6 1849 (aged 52) Rydal, Cumbria |

| Nationality |

|

| Genres | poetry, essays, biographies |

|

| |

David Hartley Coleridge (19 September 1796 - 6 January 1849) was an English poet, biographer, essayist, and teacher.

Life[]

Overview[]

Coleridge, the eldest son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was born at Clevedon, and spent his youth at Keswick among the "Lake Poets." His early education was desultory, but he was sent by Southey to Oxford in 1815. His talents enabled him to win a fellowship, but the weakness of his character led to his being deprived of it. He then went to London and wrote for magazines. From 1823 to 1828 he tried keeping a school at Ambleside, which failed, and he then led the life of a recluse at Grasmere until his death. Here he wrote Essays, Biographia Borealis (lives of worthies of the northern counties) (1832), and a Life of Massinger (1839). He is remembered chiefly for his Sonnets. He also left unfinished a drama, Prometheus.[1]

Youth[]

Coleridge was born in Clevedon, a small village near Bristol.[2] He was the eldest son of romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His sister Sara Coleridge also became a poet and translator, and his brother Derwent Coleridge a distinguished scholar and author. Hartley was named after philosopher David Hartley. His father mentions Hartley in several poems, including 'Frost at Midnight' (where he addresses him as his "babe so beautiful") and 'The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem', both of which are concerned with young Hartley's future.[2]

In the Autumn of 1800 Samuel Taylor Coleridge moved his wife and young son Hartley to the Lake District. They took a home in the vale of Derwentwater, on the bank of the Greta River, about a mile away from Greta Hall, Keswick, the future home of poet Robert Southey, which was then being built.[2] Hartley spent his early years in the care of Southey at Greta Hall,[3] which possessed the best library in the neighborhood.[2]

Hartley's brother, Derwent, says the following about Hartley's time at Greta Hall: "The unlimited indulgence with which he was treated at Greta Hall, tended, without doubt, to strengthen the many and strong peculiarities of his nature, and may perhaps have contributed to that waywardness and want of control, from which in later life he suffered so deeply."[2]

Education[]

Hartley Coleridge at the age of 10.

Hartley received his early education from his father. In 1807 he was taken by his father and William Wordsworth to Coleorton, in North West Leicestershire, and then to London. Here he visited the London theatres, and the Tower of London with Walter Scott. He was also introduced to the study of chemistry by Humphrey Davy.[2]

Hartley spent the next 8 years in constant companionship with his younger brother Derwent, at home and at school.[2] Beginning in the summer of 1808 they attended school as day-scholars at Ambleside, under the tutelage of the Rev. John Dawes.[3] During their time at the school they resided in Clappersgate. Their fellow students included the sons of their father's friend, poet Charles Lloyd. Hartley and Derwent lived in the home of an elderly woman, and enjoyed total freedom in their after-school hours. Hartley, who had no aptitude for sports, spent much of his time reading and taking walks by himself, or telling stories. He had one close friend at the time, a boy named Robert Jameson, not a fellow student, to whom he afterwards addressed a series of sonnets.[2]

In his time at the school Hartley was in constant contact with William Wordsworth and his family. He pursued his studies of English in Wordsworth's library at Allan Bank in Grasmere. His privilege of studying in the Wordsworth library was continued after the Wordsworth family moved to Rydal Mount.[2]

In 1815, he went to Oxford, as a scholar of Merton College.Essays and Marginalia, and Poems, with a memoir by his brother Derwent, appeared in 1851.[3] Derwent Coleridge made this comment about his brother's time at Oxford:

- Though far from a destructive in politics, he was always keenly alive to what he supposed to be the evils and abuses of the existing state of things both in Church and State, while he remained constant in his allegiance to what he believed to be the essentials of both... On all subjects he spoke his mind, often, through whim or impatience, more than his mind, freely, without regard to consequences.[2]

On a vacation in 1818 Hartley met poet Chauncy Hare Townshend, who said the following of him:

- I cannot easily convey to you the impression of interest which he made on my mind at that time. There was something so wonderfully original in his method of expressing himself, that on me, then a young man, and only cognisant externally of the prose of life, his sayings, all stamped with the impress of poetry, produced an effect analogous to that which the mountains of Cumberland, and the scenery of the North, were working on my southern-born eye and imagination.[2]

He had inherited much of his father's character, and his lifestyle was such that, although he was successful in gaining an Oriel fellowship, at the close of the probationary year (1820) he was judged to have forfeited it, mainly on the grounds of intemperance. The authorities would not reverse their decision; but they awarded him a gift of £300.[3] This incident deeply saddened his father, who did everything he could to try to get the decision reversed, but without success. Hartley suffered from a dependency on alcohol for the rest of his life.[2]

Career[]

Hartley Coleridge then spent 2 years in London, where he wrote short poems for the London Magazine.[3] It was around this time that he composed the fragment Prometheus, which his father regarded with much interest.[2] His next step was to become a partner in a school at Ambleside, at the suggestion of his family and friends, a venture which he himself carried out with reluctance, but this scheme failed.[3] After a struggle of 4 or 5 years, Hartley abandoned teaching, and moved to Grasmere.

From 1826 to 1831, he wrote occasionally in Blackwood's Magazine, to which he was introduced by his friend, John Wilson. His contributions to this periodical form part of the general collection of his Essays.[2]

In 1830 a Leeds publisher, F.E. Bingley, made a contract with him to write biographies of Yorkshire and Lancashire worthies. These were afterwards republished under the title of Biographia Borealis (1833) and Worthies of Yorkshire and Lancashire (1836). Bingley also printed a volume of Coleridge's poems in 1833, and Coleridge lived in his house until the contract came to an end through the bankruptcy of the publisher.[3]

Later life[]

From this time, except for 2 short periods in 1837 and 1838 when he acted as master at Sedbergh School, Coleridge lived quietly at Grasmere and (from 1840 to 1849) at Rydal, spending his time in study and wanderings about the countryside. His figure was as familiar as Wordsworth's, and he made many friends among the locals.[3]

In 1834 he lost his father. Hartley made the following comment about his father's death in a letter to his mother:

- though I cannot say that I was much surprised, yet so little had I prepared my mind for the loss, that it fell upon me as the fulfilment of an unbelieved prophecy: and even yet, though I know it, I hardly believe it. I do not feel fatherless. I often find my mind disputing with itself- What would my father think of this? and when the recollection awakes, that I have no father, it appears more like a possible evil than an actual bereavement.[2]

In 1839 he brought out his edition of Massinger and John Ford, with biographies of both dramatists.[3]

The closing decade of Coleridge's life was wasted in what he himself called "the woeful impotence of weak resolve."[3] On the death of his mother in 1845, he was placed, by means of an annuity on his life, on a footing of complete independence, but he lived for only 3 more years,[2] dying on 6 January 1849.[3]

Writing[]

The prose style of Hartley Coleridge is marked by much finish and vivacity; but his literary reputation must chiefly rest on the sanity of his criticisms, and above all on his Prometheus, an unfinished lyric drama, and on his sonnets. As a sonneteer he achieved real excellence, the form being exactly suited to his sensitive genius.[4]

Sonnets of this Century (1887), edited by William Sharp, declared that "as in the case of Charles Tennyson Turner, his reputation rests solely on his sonnets."[5]

Essays and Marginalia, and Poems (with a memoir by his brother Derwent), appeared in 1851.[4]

Critical introduction[]

Hartley Coleridge always classed himself among ‘the small poets,’ and it is true he was not born for great and splendid achievements; but there are some writers for whom our affection would be less if they were stronger, more daring, more successful; and Hartley Coleridge is one of these. We think of him as the visionary boy, whom his father likened to the moon among thin clouds, moving in a circle of his own light,— as the fairy voyager of Wordsworth’s prophetic poem, whose boat seemed rather

- ‘To brood on air than on an earthly stream.’

We think of him as the elvish figure one might meet forty years later by Grasmere side, too soon an old man and white-haired, with now and then an expression of pain, a half-tone in his voice that betrayed some sense of incompleteness or failure, but with the full eye still bright and soft; the speech still rippling out fancy and play and wisdom; the heart, in spite of sorrow and the injuries of time, still as Wordsworth knew it,

- ‘A young lamb’s heart among the full-grown flocks.’

A great poet is a toiler, even when his toil is rapturous. Hartley Coleridge did not and perhaps could not toil. Good thoughts came to him as of free grace; gentle pleasures possessed his senses; loving-kindnesses flowed from his heart, and took as they flowed shadows and colours from his imagination; and all these mingled and grew mellow. And so a poet’s moods expressed themselves in his verse; but he built no lofty rhyme. The sonnet, in which a thought and a feeling are wedded helpmates suited his genius; and of his many delightful sonnets some of the best are immediate transcripts of the passing mood of joy or pain. ‘To see him brandishing his pen,’ a friend has written, ‘and now and then beating time with his foot, and breaking out into a shout at any felicitous idea, was a thing never to be forgotten…. His sonnets were all written instantaneously, and never, to my knowledge, occupied more than ten minutes.’ Perhaps because of this happy facility they often fall short of complete attainment; sometimes the vigour of conception suddenly declines, sometimes the touch loses its precision; nor is the poetic mood from which they originate always delivered by the imagination from its surrounding circumstance of prose, or its alloy of humbler feeling.

But all that Hartley Coleridge has written is genuine, full of nature, sweet, fresh, breathing charity and reconciliation. His poems of self-portrayal are many, and of these not a few are pathetic with sense of change and sorrowing self-condemnation; yet his penitence had a silver side of hope, and one whose piety was so unaffected, whose faith though ‘thinner far than vapour’ had yet outlived all frowardness, could not desperately upbraid even his weaker self. For all that is sweet and venerable—for the charm of old age, for the comeliness of ancient use and wont, for the words of sacred poet or prophet, for the traditions of civility, for the heritage of English law and English freedom, for the simple humanities of earth, for fatherhood and motherhood, Hartley Coleridge had a heartfelt and tender reverence. And with a more exquisite devotion he cherished all frail, innocent, and dependent creatures; small they should be or they could not look to their quaint little poet as a protector. To think of the humming-bird’s or the cricket’s glee made him happy; he bowed over the forget-me-not blossom as if it were a sapphire amulet against all mortal taint, and over the eye-bright ‘gold-eyed weedie,’ which owns such holy, medicinal virtue. He loved with the naïveté of innocent-hearted old bachelorhood the paradise of maidenhood; with all its sweet she-slips, in Shakespeare’s play and Stothard’s page, and, better still, on English lawn or by English fireside. And who has been laureate to as many baby boys and ‘wee ladies sweet’ as Hartley Coleridge? Rounding the lives of all little children and all helpless things he felt a nearness of some strong protecting Love which called forth his deepest instincts of piety.

In Grasmere churchyard, close to the body of Wordsworth, rests that of Hartley Coleridge; so a Presence of strength and plain heroic magnitude of mind environs him. And hard by a stream goes murmuring to the lake. As a mountain rivulet to a mountain lake, so is Hartley Coleridge’s poetry to that of Wordsworth; and the stream has a melodious life and a freshness of its own.[6]

Recognition[]

4 of his poems ("The Solitary-Hearted," "Song," "Early Death," and "Friendship") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[7]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Poems, Songs and Sonnets. Leeds, UK: John Cross, 1833.

- Poems (edited with a memoir by Derwent Coleridge). (2 volumes), London: Edward Moxon, 1851. Volume 1, Volume 2.

- The Complete Poetical Works (edited by Ramsay Colles). London: Routledge / New York: Dutton, 1908.

- Hartley Coleridge. London: Ernest Benn, 1931.

- New Poems: Including a selection from his published poetry (edited by Earl Leslie Griggs). London: Oxford University Press, 1942.

- Bricks without Mortar: Selected poems (edited by Lisa Gee). London: Picador, 2000.

Non-fiction[]

- Biographia Borealis; or Lives of distinguished northerns. London: Whitaker, Treacher / Leeds, UK: F.E. Bingley, 1833.

- also published as The Worthies of Yorkshire and Lancashire: Being lives of the most distinguished persons that have been born in, or connected with, those provinces. London: Whittaker / Simpkin, Marshall / Leeds, UK: John Cross / Manchester, UK: Bancks / Liverpool: Grapel / Leeds, UK: F.E. Bingley 1836.

- also published as Life of Northern Worthies. (3 volumes), London: Edward Moxon, 1852.

- The Life of Andrew Marvel. Hull, UK: A.D. English, 1835.

- Essays and Marginalia (edited by Derwent Coleridge). (2 volumes), London: Edward Moxon, 1851. Volume 1; Volume 2.

- Essays: On parties in poetry / On the character of Hamlet. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1925.

Edited[]

- The Dramatic Works of Massinger and Ford. London: Edward Moxon, 1840.

Letters[]

- Letters of Hartley Coleridge (edited by Grace Evelyn (Riley) Griggs & Earl Leslie Griggs). London & New York, Oxford University Press, 1941.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[8]

See also[]

"To A Cat" by Hartley Coleridge (read by Tom O'Bedlam)

References[]

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Coleridge, Hartley". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 676-677.

- Hartley Coleridge: His life and work, E.L. Griggs, R. West, 1977.

- Hartley Coleridge: A reassessment of his life and work, Andrew Keanie, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Coleridge, Hartley," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 89. Web, Dec. 26, 2017.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Memoir of Hartley Coleridge, Derwent Coleridge, from Poems, Volume 1 (London: Moxon, 1851).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Britannica 6, 676.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Britannica 6, 677.

- ↑ Hartley Coleridge (1796-1849), Sonnet Central. Web, July 22, 2013.

- ↑ from Edward Dowden, "Critical Introduction: Hartley Coleridge (1796–1849)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 15, 2016.

- ↑ Alphabetical list of authors: Brontë, Emily to Cutts, Lord, Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 16, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Hartley Coleridge, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Mar. 15, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Summer Rain"

- Sonnet 7

- Hartley Coleridge 1796-1849 at the Poetry Foundation

- Hartley Coleridge in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 - 4 poems ("The Solitary-Hearted," "Song," "Early Death," and "Friendship").

- Hartley Coleridge at Sonnet Central (5 sonnets)

- Coleridge in The English Poets: An anthology: Sonnet: "Long time a child, and still a child, when years", ""To a Lofty Beauty, from Her Poor Kinsman," "May, 1840," "To a Deaf and Dumb Little Girl," Stanzas: "She was a queen of noble Nature’s crowning", Song: "She is not fair to outward view", "Summer Rain,"

- Coleridge in A Victorian Anthology: "To the Nautilus," "The Birth of Speech," "Whither?," "To Shakespeare," "Ideality," "Song," "Prayer," "Multum Dilexit"

- Selected Poetry of Hartley Coleridge (1796-1849) (9 poems) at Representative Poetry Online.

- Hartley Coleridge at PoemHunter (17 poems)

- Hartley Coleridge at Poetry Nook (96 poems)

- Audio / video

- Books

- Works by Hartley Coleridge at Project Gutenberg

- Hartley Coleridge at Amazon.com

- About

- Hartley Coleridge in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Coleridge, Hartley in the Dictionary of National Biography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at "Coleridge, Hartley".

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

|