Template:Refimprove

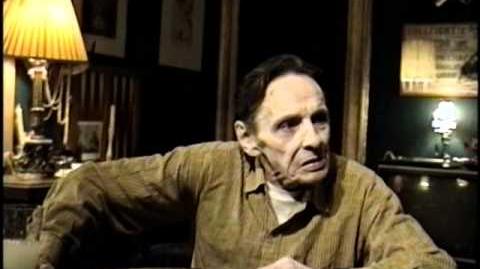

Herbert Huncke (1915-1996) in 1985. Photo by Christopher Felver. Courtesy Wikipedia.

Herbert Edwin Huncke (January 9, 1915 - August 8, 1996) was an American poet and prose writer. A member of the Beat Generation, he is reputed to have coined that term.[1]

Life[]

Youth[]

Born in Greenfield, Massachusetts and reared in Chicago, Herbert Huncke was a street hustler, high school dropout and drug user. Huncke's life was centered around living as a hobo, jumping trains across the vast expanse of the United States, bonding through a shared destitution and camaraderie with other vagrants. Although Huncke later came to regret his loss of family ties, in his autobiography, Guilty of Everything, he states that his lengthy jail sentences were a partial result of his lack of family support. Huncke left Chicago as a teenager after his parents divorced.

New York City and Times Square[]

Huncke hitchhiked to New York City in 1939. He was dropped off at 103rd and Broadway, and he asked the driver how to find 42nd Street. "You walk straight down Broadway," the man said, "and you will find 42nd Street." Huncke, always a stylish dresser, bought a boutonnière for his jacket and headed for 42nd Street. For the next 10 years, Huncke was a 42nd Street regular and became known as the "Mayor of 42nd Street."

In early 1940s Huncke was invited to meet Dr. Alfred Kinsey, from Indiana University, regarding research on the sexual habits of the American male. From Indiana University Kinsey wrote Huncke at the hotel where he was living. The letter was returned, postmarked January 26, 1943. Huncke had moved on.

Kinsey and Huncke met up several times in mid-decade and Kinsey paid Huncke two dollars for every recruit he brought to talk about their sex lives. "I told one cat, look, if you're going to be upset if he asks you if you slept with your mother, don't go."

Huncke had been a writer, unpublished, since his days in Chicago and gravitated toward literary types and musicians. In the music world, Huncke visited all the jazz clubs and associated with Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker and Dexter Gordon (with whom he was once busted on 42nd Street for breaking into a parked car).

At this point, Huncke's regular haunts were 42nd Street and Times Square, where he associated with a variety of people, including prostitutes (both male and female) and sailors.

During World War II, Huncke shipped out to sea as a United States Merchant Marine to ports in South America, Africa and Europe. He landed on the beach of Normandy 3 days after the invasion.

Aboard ships, Huncke would overcome his drug addiction or maintain it with morphine syrettes supplied by the ship medic. When he returned to New York, he returned to 42nd Street.

It was after such a trip where he met then-unknown William S. Burroughs, who was selling a sub-machine gun and a box of syrettes. Their meeting was not cordial: from Burroughs' appearance and manner, Huncke suspected that he was "heat" (undercover police or FBI).[2] Assured that Burroughs was harmless, Huncke bought the morphine and, at Burroughs' request, immediately gave him an injection. Burroughs later wrote a fictionalized account of the meeting in his debut novel, Junkie:

- Waves of hostility and suspicion flowed out from his large brown eyes like some sort of television broadcast. The effect was almost like a physical impact. The man was small and very thin, his neck loose in the collar of his shirt. His complexion faded from brown to a mottled yellow, and pancake make-up had been heavily applied in an attempt to conceal a skin eruption. His mouth was drawn down at the corners in a grimace of petulant annoyance.[1]

Huncke also became a close friend of Joan Adams Vollmer Burroughs, William's common-law wife, sharing with her a taste for amphetamines. In the late 1940s he was invited to Texas to grow marijuana on the Burroughs farm. It was here he renewed his acquaintance with the young Abe Green, a fellow train jumper and much later on in the early beatnik scene, a regular reciter of his own enigmatic brand of spontaneous poetry. Despite his comparative youth, Green was often referred to by Hunke as "Old Faithful". Hunke valued loyalty and it is thought that Abe Green was of "inestimable assistance" to Lucien Carr and Jack Kerouac when it came to the concealment of the weapon used to murder David Kammerer some years later.

In early 1940s Huncke was invited to meet Dr. Alfred Kinsey, from Indiana University, regarding research on the sexual habits of the American male. He was interviewed by Kinsey, and recruited fellow addicts and friends to participate. Huncke had been a writer, unpublished, since his days in Chicago and gravitated toward literary types and musicians. In the music world, Huncke visited all the jazz clubs and associated with Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker and Dexter Gordon (with whom he was once busted on 42nd Street for breaking into a parked car).

When Huncke met Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs, they were interested in writing and also unpublished. They were inspired by his stories of 42nd Street life, his criminal past, his street slang. and his vast experience with drugs. Kerouac described Huncke in his "Now it's Jazz" reading from Desolation Angels, chapter 77: "Huck, whom you'll see on Times Square, somnolent and alert, sad, sweet, dark, holy. Just out of jail. Martyred. Tortured by sidewalks, starved for sex and companionship, open to anything, ready to introduce a new world with a shrug."

Although it was his passion for thievery, heroin use and the outlaw lifestyle which fueled his daily activities, when Huncke was caught he refused to inform on his friends. In the late 1940s, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Melody and "Detroit Redhead" flipped a car in Queens, New York, while trying to run down a motorcycle cop. Although Huncke was not at the scene of the crime, he was arrested in Manhattan because he resided with Ginsberg, and Huncke ended up receiving the lengthy prison sentence. "Someone had to do the bit," Huncke said years later.

Writing career[]

Huncke was a natural storyteller, a unique character with a paradoxically honest take on life. Later, after the formation of the so-called Beat Generation, members of the Beats encouraged Huncke to publish his notebook writings, which he did with limited success in 1964 with Diane di Prima's Poet's Press. (Huncke's Journal).

Huncke used the word "Beat" to describe someone living with no money and few prospects. "Beat to my socks," he said. Huncke coined the phrase in a conversation with Jack Kerouac, who was interested in how their generation would be remembered. "I'm beat," was Huncke's reply, meaning tired and beat to his socks. Kerouac used the term to describe an entire generation. Jack Kerouac later insisted that "Beat" was derived from beatification, to be supremely happy. However, it is thought that this definition was a defense of the beat way of life, which was frowned upon and offended many American sensibilities.

He also starred in his only acting role in James Rasin and Jerome Poynton's The Burning Ghat.

Later life[]

His autobiography, titled Guilty of Everything, was lived in the 1940s and 1960s but published in the 1990s.

He gave one lecture to students at Ginsberg's Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute in 1982, an event celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the publication of On The Road.[3]

For several years he lived in a garden apartment on East 7th Street near Avenue D in New York City, supported financially by his friends David Sands, Jerome Poynton, Tim Moran, Gani Remorca, Raymond Foye and many others. In his last few years, he lived in the Chelsea Hotel, where his rent came from financial support from Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead, whom Huncke never met.

In his last year, he performed live with Patti Smith at the annual Kerouac Festival in Lowell, Massachusetts.[1]

He died August 8, 1996, in a New York City hospital.[3]

Recognition[]

The ORIGINAL BEATS outtakes HERBERT HUNCKE

Huncke was featured in several documentaries about the Beat generation, including Janet Forman's The Beat Generation: An American dream, Richard Lerner and Lewis MacAdams' What Happened to Kerouac? and John Antonelli's Kerouac, the Movie.

In popular culture[]

Huncke was immortalized in Kerouac's On the Road as the character Elmer Hassel.

John Clellon Holmes mentioned Huncke (called "Albert Ancke") in Chapter 14 of part 2 of Go: "A sallow, wrinkled little hustler, hatless and occupying a crumpled sport shirt as though crouched in it to hide his withered body."

Huncke was admired by David Wojnarowicz in his personal diaries, In the Shadow of the American Dream, where their meetings/dates are documented.

Frank McCourt mentions knowing Huncke in Chapter 16 of Teacher Man: "Alcohol is not his habit but he'll kindly allow you to buy him a drink at Montero's. His voice is deep, gentle and musical. He never forgets his manners and you'd rarely think of him as Huncke the Junkie. He respects law and obeys none of it."

Publications[]

Short fiction[]

- Elsie John and Joey Martinez: Two stories. New York: Pequod Press, 1979.

Non-fiction[]

- Guilty of Everything: Autobiography (edited by Don Kennison, with foreword by William S. Burroughs). Madras & New York: Hanuman Press, 1987; New York: Paragon House, 1990. ISBN 1-55778-044-7;

- The Evening Sun Turned Crimson. Amsterdam: Neptune Books, 1990; (Cherry Valley, NY: Cherry Valley Editions, 1980. ISBN 0-916156-43-5.

- Again–The Hospital (broadside). Louisville, KY: White Fields Press, 1995. (single sheet, 12" by 22", illustrated with a photo of Huncke)

- John Tytell, Notes from the Beat Underground: An interview with Herman Huncke. Binley Woods, Coventry, UK: Beat Scene Press, 2013.

Collected editions[]

- The Herbert Huncke Reader (edited by Ben Schafer). New York: Morrow, 1997. ISBN 0-688-15266-X (includes complete texts of The Evening Sun Turned Crimson and Huncke's Journal)

Journal[]

- Huncke's Journal (edited by Diane DiPrima, with foreword by Allen Ginsberg). New York: Poets Press, 1965.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[4]

Audio / video[]

Herbert Huncke reads "Comments", April 4, 1994-0

Herbert Huncke reads "Two for One"

Herbert Huncke Reads Three Poems

- From Dream to Dream (CD). [Netherlands?]: Music & Words, 1994.

- Guilty of Everything (2-CD of Huncke's 1987 live reading at Ins & Outs Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands). San Francisco: Unrequited Records, 2012.[4]

See also[]

References[]

- Charters, Ann (ed.). The Portable Beat Reader. Penguin Books. New York. 1992. ISBN 0-670-83885-3 (hc); 0140151028 (pbk)

- McCourt, Frank. "Teacher Man". Scribner. New York. 2005.

- Mahoney, Denis; Martin, Richard L.; Whitehead, Ron (ed.). A Burroughs Compendium: Calling the Toads. New York. 1998. ISBN 0-9659826-0-2.

- Mullin, Rick, Huncke: A Poem by Rick Mullin. Illustrated by Paul Weingarten. Seven Towers, Dublin, Ireland. 88 pgs. 2010. ISBN 978-0-9562033-7-3

Fonds[]

- Herbert Huncke Papers at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Columbia University

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Herbert Huncke, Beat Museum. Web, Mar. 5, 2019.

- ↑ Huncke interviewed in Arena documentary on Burroughs, BBC TV 1983.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Levi Asher, Herbert Huncke, Literary Kicks, August 24, 1994. Web, Mar. 5, 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Search results = au:Herbert Huncke, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Mar. 5, 2019.

External links[]

- Prose

- Books

- Herbert E. Huncke at Amazon.com

- About

- Metroactive.com article, Herbert Huncke, the unsung Beat, finally gets his due, by Harvey Pekar

- Herbert Huncke at Lit Kicks

- The Writers Notebooks of Herbert Huncke at Reality Studio

- Herbert Huncke at Beat Museum

- Huncke-Times

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

|