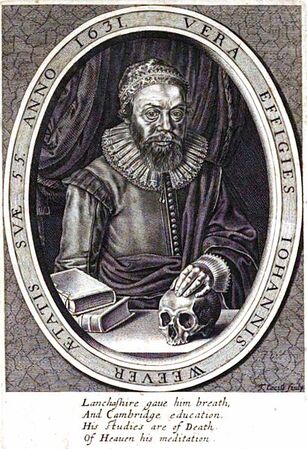

John Weever (1576-1632), from Ancient Funeral Monuments, 1631. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

John Weever (1576-1632) was an English poet and antiquary.[1]

Life[]

Overview[]

A native of Lancashire, Weaver was born in 1576. He was educated at Queens' College, Cambridge, where he resided for about 4 years from 1594. In 1599 he published Epigrammes in the Oldest Cut and Newest Fashion, containing a sonnet on Shakespeare, and epigrams on Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, Ben Jonson, William Warner and Christopher Middleton, all of which are valuable to the literary historian. In 1601 he published The Mirror of Martyrs or The Life and Death of ... Sir John Oldcastle, which he calls in his preface the "first trew Oldcastle," perhaps on account of the fact that Shakespeare's Falslaff originally appeared as Sir John Oldcastle. In the 4th stanza of this long poem, in which Sir John is his own panegyrist, occurs a reminiscence of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar which serves to fix the date of the play. After travelling in France, the Low Countries and Italy, Weever settled in Clerkenwell, and made friends among the chief antiquaries of his time. The result of extensive travels in his own country appeared in Funerall Monuments (1631), now valuable on account of the later obliteration of the inscriptions.[1]

Youth and education[]

Weever, a native of Lancashire, was admitted to Queens' College, Cambridge, as a sizar on 30 April 1594. His tutor was William Covell.[2] He earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1598.[3][4] He retained through life an affection for his college.[2]

Poet[]

Retiring to his Lancashire home about 1598, he studied carefully and appreciatively current English literature, and in 1599 he published a volume entitled Epigrammes in the oldest Cut and newest Fashion. A twise seven Houres (in so many weekes) Studie. No longer (like the Fashion) not unlike to continue. The first seven. John Weever (London by V.S. for Thomas Bushell), 1599, 12mo. The whole work was dedicated to a Lancashire patron, Sir Richard Houghton of Houghton Tower, high sheriff of the county.[2]

A portrait engraved by Thomas Cecil is prefixed, and described the author as 23 at the date of publication, 1599. But Weever in some introductory stanzas informs the reader that most of the epigrams were written when he was only 20. He speaks of his Cambridge education, and confesses ignorance of London.[2]

Weever produced another volume of verse. This bore the title: The Mirror of Martyrs; or, The life and death of that thrice valient Capitaine and most godly Martyre Sir John Oldcastle, knight, Lord Cobham, 1601, sm. sq. 8vo (London, by V. S. for William Wood). There are dedications to 2 friends, William Covell, B.D., the author's Cambridge tutor, and Richard Dalton of Pilling.[2]

Subsequently Weever published a thumb-book (1½ inch in height) giving a poetical history of Christ beginning with the birth of the Virgin. The title-page ran ‘An Agnus Dei. Printed by V. S. for Nicholas Lyng, 1606.’ The dedication ran: ‘To Prince Henry. Your humble servant. Jo. Weever.’ The only copy known is in the Huth Library (cf. Brydges, Censura Literaria, ii.; Huth Library Cat.)[5]

Antiquary[]

In the early years of the 17th century Weever travelled abroad. He visited Liège, Paris, Parma, and Rome, studying literature and archæology (cf. Funerall Monuments, pp. 40, 145, 257, 568). Finally he settled in a large house built by Sir Thomas Chaloner in Clerkenwell Close, and turned his attention exclusively to antiquities. He made antiquarian tours through England, and he designed to make archæological exploration in Scotland if life were spared him. He came to know the antiquaries at the College of Arms and elsewhere in London, and made frequent researches in the libraries of Sir Robert Cotton and Sir Simonds D'Ewes.[5]

His chief labours saw the light in a folio volume extending to nearly 900 pages, and bearing the title Ancient Funerall Monuments within the United Monarchie of Great Britaine, Ireland, and the Islands adjacent, with the dissolved monasteries therein contained, their Founders and what Eminent Persons have been in the same interred (London, 1631, fol.). A curious emblematic frontispiece was engraved by Thomas Cecil, as well as a portrait of the author, ‘æt. 55 Ao 1631.’[5]

Weever dedicated his work to Charles I. In an epistle to the reader he acknowledges the encouragement and assistance he received from his "deare deceased friend" Augustine Vincent, and from the antiquary Sir Robert Cotton, to whom Vincent first introduced him. He also mentions among his helpers Sir Henry Spelman, John Selden, and Sir Simonds D'Ewes. A copy which Weever presented to his old college (Queens') at Cambridge is still in the library there, and has an inscription in his autograph (facsimile in Pink's Clerkenwell, p. 351).[5]

Weever, who dated the address to the reader in his Funerall Monuments from his house in Clerkenwell Close, was buried in 1632 in the church of St. James's, Clerkenwell. The church was subsequently entirely rebuilt (cf. Pink's Clerkenwell, p. 48). The long epitaph in verse inscribed on his tomb is preserved in Stow's Survey of London (1633, p. 900, cf. Strype's edition, bk. iv. p. 65; Gent. Mag. 1788, ii. 600).

Writing[]

Epigrams[]

The Epigrams, which are divided into 7 parts (each called a "week," after the manner of French religious poet Du Bartas), are in crude and pedestrian verse.[2]

But the volume owes its value, apart from its rarity, to its mention and commendation of the chief poets of the day. The most interesting contribution is a sonnet (No. 22 of the 4th week) addressed to Shakespeare which forcibly illustrates the admiration excited among youthful contemporaries by the publication of Shakespeare's early works — his narrative poems, his Romeo and Juliet, and his early historical plays.[2]

Hardly less valuable to the historian of literature are Weever's epigrams on Edmund Spenser's poverty and death, on Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, Ben Jonson, John Marston, William Warner, Robert Allott, and Christopher Middleton. In his epigram on Edward Alleyn, he asserts that Rome and Roscius yield the palm to London and Alleyn. A copy of this extremely rare volume is in the Malone collection at the Bodleian Library.[2]

Mirror for Martyrs[]

The work was, the author tells us, written 2 years before publication, and was possibly suggested by the controversy about Sir John Oldcastle that was excited in London in 1598 by the production of Shakespeare's Henry IV. In that play the great character afterwards renamed Falstaff originally first bore the designation of Sir John Oldcastle, to the scandal of those who claimed descent from the lollard leader or sympathised with his opinions and career (cf. Shakespeare's Centurie of Prayse, pp. 42, 165). Weever calls his work the "true Oldcastle," doubtless in reference to the current controversy.[2]

Weever displays at several points his knowledge of Shakespeare's recent plays.[2] He vaguely reflects Shakespeare's language in Henry IV (pt. ii. line 1) when referring to Hotspur's death and the battle of Shrewsbury (stanza 113).[5]

Similarly in stanza 4 he notices the speeches made to "the many-headed multitude" by Brutus and Mark Antony at Cæsar's funeral. These speeches were the invention of Shakespeare in his play of Julius Cæsar, and it is clear that Weever had witnessed a performance of Shakespeare's play of Julius Cæsar before writing of Cæsar's funeral. Weever's reference is proof that Julius Cæsar was written before Weever's volume was published in 1601. There is no other contemporary reference to the play by which any limits can be assigned to its date of composition. The piece was not published until 1623, in the First Folio of Shakespeare's works.[5]

As in his earlier volume, Weever mentions Spenser's distress at the close of his life (stanza 63).[5]

4 perfect copies of Weever's Mirror of Martyres’ are known; they are respectively in the Huth, Britwell, and Bodleian libraries, and in the Pepysian Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. The only other copy now known is imperfect, and is in the British Museum. The poem was reprinted for the Roxburghe Club in a volume edited by Mr. Henry Hucks Gibbs (afterwards Lord Aldenham) in 1873.[5]

Funeral Monuments[]

Almost all Weever's sepulchral inscriptions are now obliterated. His transcripts are often faulty and errors in dates abound (cf. Wharton, Angl. Sacra, par. i. p. 668; Gent. Mag. 1807, ii. 808). But to the historian and biographer the book, despite its defects, is invaluable. A new edition appeared in 1661, and a 3rd, with some addenda by William Tooke, in 1767. Weever's original manuscript of the work is in the library of the Society of Antiquaries (Nos. 127–8).[5]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Epigrammes: In the oldest cut and newest fashion. London: Valentine Sims, for Thomas Bushell, 1599

- (edited by Ronald Brunlees McKerrow). London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1911.

- Faunus and Melliflora; or, The original of our English satyres. London: Valentine Sims, 1600

- (edited by Arnold Davenport). Liverpool: University Press of Liverpool / London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1948.

- An Agnus Dei. London: Valentine Sims, for Nicholas Lyng, 1601; London: Nicholas Okes, for Iohn Smethwicke, 1610.

- The Mirror of Martyrs; or, The life and death of ... Sir John Oldcastle. London: Valentine Simmes, for William Wood, 1601.

- The Whipping of the Satyre. London: John Flasket, 1601

- (edited by Arnold Davenport). Liverpool: University Press of Liverpool, 1951.

- Rochester Bridge: A poem written in 1601 (edited by William Brenchley Rye). London: Mitchell & Hughes, for the Kent Archæological Society, 1887.

Non-fiction[]

- Ancient Funerall Monuments. London: Thomas Harper, 1631.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[6]

See also[]

References[]

Lee, Sidney (1899) "Weever, John" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 60 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 149-150. Wikisource, Web, Jan. 5, 2017.

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Weever, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. 29 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 467.. Wikisource, Web, May 9, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Lee, 149.

- ↑ John Weever(1576-1632), English Poetry, 1579-1830, Center for Applied Technologies in the Humanities, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University. Web, Jan. 7, 2016.

- ↑ The Dictionary of National Biography says, though, that he "seems to have left the university without a degree." Lee, 149.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Lee, 150.

- ↑ Search results = au:John Weever, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Jan. 5, 2017.

External links[]

- Poems

- John Weever (1576-1632) info & 6 poems at English Poetry, 1579-1830

- Books

- John Weever at Amazon.com

- About

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Weever, John

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.. Original article is at Weever, John

|