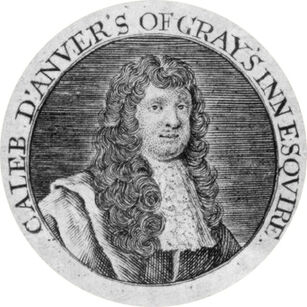

Caleb D'Anvers (Nicholas Amburst) (1697-1742), from The Craftsman. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Nicholas Amhurst (October 16, 1697 - April 27, 1742) was an English poet and political writer.

Life[]

Youth and education[]

Amhurst was born at Marden, Kent. He was educated at the Merchant Taylors' School, and received an exhibition (1716) to St John's College, Oxford in 1716.[1]

In 1719 he was expelled from the university, ostensibly for his irregularities of conduct, but in reality, according to his own account, because of his Whig principles, which were sufficiently evident in a congratulatory epistle to Addison, in Protestant Popery; or, The convocation (1718), an attack on the opponents of Bishop Hoadly, and in The Protestant Session ... by a of the Constitution Club at Oxford (1719), addressed to James, first Earl Stanhope, and printed anonymously, but doubtless by Amhurst. He had satirized Oxford morals in Strephon's Revenge; a Satire on the Oxford Toasts (1718), and he attacked from time to time the administration of the university and its principal members..[1]

Early career[]

On his expulsion from Oxford in June 1719, Amhurst seems to have settled in London, and to have adopted literature as his profession.[2]

An old Oxford custom on public occasions permitted some person to deliver from the rostrum a humorous, satirical speech, full of university scandal. This orator was known as Terrae filius. In 1721 Amhurst produced a series of bi-weekly satirical papers under this name, which ran for 7 months and incidentally provides much curious information. These publications were reprinted in 1726 in 2 volumes as Terrae Filius; or the secret history of the University of Oxford; several essays....[1]

He collected his poems in 1720, and wrote another university satire, Oculus Britanniae, in 1724.[1]

The Craftsman[]

On leaving Oxford for London he became a prominent pamphleteer on the opposition side. On the 5th of December 1726 he issued the debut issue of the Craftsman, a weekly periodical, which he conducted under the pseudonym of Caleb D'Anvers. The paper contributed largely to the final overthrow of Sir Robert Walpole's government, and reached a circulation of i0,000 copies.[1] For this success Amhurst's editorship was not perhaps chiefly responsible. It was the organ of Lord Bolingbroke and William Pulteney, the latter of whom was a frequent and caustic contributor.[1]

In 1737 an imaginary letter from Colley Cibber was inserted, in which he was made to suggest that many plays by Shakespeare and the older dramatists contained passages which might be regarded as seditious. He therefore desired to be appointed censor of all plays brought on the stage. This was regarded as a "suspected" libel, and a warrant was issued for the arrest of the printer. Amhurst surrendered himself instead, and suffered a short imprisonment.[1]

When Pulteney and his friends made their peace with the government, they did nothing for Amhurst; and the closing portion of his life appears to have been spent in much poverty and distress.[2]

He died at Twickenham, 12 April 1742, of a broken heart, it is said, and according to one account was indebted to the charity of his printer, Richard Francklin, for a tomb.[3]

Writing[]

In 1718 Amhurst published a poem in 5 cantos, called Protestant Popery; or, The convocation (printed by Edmund Curll, without the author's name), in which Bishop Hoadly is eulogised, and the same year he wrote a shorter poem called "Strephon's Revenge: A satire on the Oxford toasts," which deals severely with the license and profligacy prevailing in the university town. He was also the author (in all probability) of a poem called The Protestant Session.... by a member of the Constitution Club at Oxford, printed by Curll in 1719, in which Stanhope is addressed in a strain of excessive adulation.[2]

In 1721 he began a series of 50 periodical papers calle Terræ Filius, which appeared every Wednesday and Saturday from 11 January to 6 July. The Terræ Filius was Amhurst's revenge on the university, which it satirises very severely. It is written with much liveliness, and occasionally with a good deal of humor, and though no doubt greatly exaggerated it is of considerable value owing to the ample description it gives of life at Oxford in the 1st quarter of the 18th century. No. 45 of the series contains the narrative of Amhurst's expulsion from the university, and No. 50 an account of the Oxford Constitution Club. A 2nd edition, with a letter to the vice-chancellor, appeared in 1726.[2]

In 1720 Amhurst published a small volume of Poems on Several Occasions, which include paraphrases of chapter 1 of Genesis and the chapter 14 of Exodus; a number of imitations of Catullus; several epigrams on the author's Oxford enemies; and an account of the invention of the corkscrew. Without displaying any high poetical power, Amhurst knew how to turn out smooth and fluent verses, not deficient in a certain wit and liveliness, although occasionally disfigured by a good deal of coarseness. The ‘Poems’ were successful enough to call for a 2nd edition in 1723, to which was added "The Test of Love."[2]

In 1722 Amhurst published "The British General: A poem sacred to the memory of John Duke of Marlborough," in 1722 "The Conspiracy," inscribed to Lord Cadogan, and in 1724 "Oculus Britanniæ," a satirical poem on his old enemy the university of Oxford. Of his subsequent literary career we have few particulars.[2]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Protestant Popery; or, The convocation. London: E. Curll, 1718.

- The Protestant Session: A poem. London: E. Curll, 1719.

- Poems on Several Occasions. London: R. Francklin, 1720

- expanded edition, 1723.

- The British General. London: R. Francklin, 1722.

- A collection of Poems on Several Occasions; publish'd in 'The Craftsman', by Caleb D'Anvers, of Gray's-Inn, Esq. London: R. Francklin, 1731.

Non-fiction[]

- The Doctrine of Innuendo's Discuss'd; or, The liberty of the press maintain'd. London: 1731.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[4]

See also[]

References[]

Low, Sidney James Mark (1885) "Amhurst, Nicholas" in Stephen, Leslie Dictionary of National Biography 1 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 361-363. Wikisource, Web, Jan. 25, 2019.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Amhurst, Nicholas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 853. Wikisource, Web, Jan. 25, 2019.

Notes[]

External links[]

- Poems

- Nicholas Amhurst in the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive

- Nicholas Amhurst at PoemHunter (90 poems)

- Books

- Nicholas Amhurst at Amazon.com

- About

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Amhurst, Nicholas

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article was at Nicholas Amhurst

|