Osbert Sitwell (1892-1969). Courtesy World War I and English Poetry.

| Sir Osbert Sitwell | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Francis Osbert Sachverell Sitwell December 6 1892 London, England |

| Died |

May 4 1969 (aged 76) near Florence, Italy |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 1919–1962 |

| Partner(s) | David Horner |

| Relative(s) | George Sitwell (father), Edith Sitwell (sister), Sacheverell Sitwell (brother) |

Sir Francis Osbert Sacheverell Sitwell, 5th baronet (6 December 1892 – 4 May 1969) was an English writer. His elder sister was Edith Sitwell and his younger brother was Sacheverell Sitwell; like them he devoted his life to art and literature.

Life[]

Youth and education[]

Sitwell was born at 3 Arlington Street, London. His parents were Lady Ida Emily Augusta (née Denison) and Sir George Reresby Sitwell, 4th baronet, genealogist and antiquarian. He grew up in the family seat at Renishaw Hall, Derbyshire, and at Scarborough, North Yorkshire.

He went to Ludgrove School, then to Eton College from 1906 to 1909. For many years his entry in Who's Who contained the phrase "Educ: during the holidays from Eton."

Army[]

In 1911 he joined the Sherwood Rangers but, not cut out to be a cavalry officer, transferred to the Grenadier Guards at the Tower of London from where, in his off-duty time, he could frequent theatres, art galleries, and the like.

In 1914, with the start of World War I, Sitwell's civilised life was exchanged for the trenches of France near Ypres, Belgium. It was here that he wrote his earliest poetry, describing it as "Some instinct, and a combination of feelings not hitherto experienced united to drive me to paper". "Babel" was published in The Times on 11 May 1916. In the same year, he began literary collaborations and anthologies with his brother and sister, the trio being usually referred to simply as "The Sitwells".

Career[]

In 1918 he left the Army with the rank of captain, and contested the 1918 general election as the Liberal Party candidate for Scarborough and Whitby, finishing 2nd. Later he moved towards the political right, though politics were very seldom explicit in his writings.

Sitwell devoted himself to poetry, art criticism and controversial journalism. Together with his brother, he sponsored a controversial exhibition of works by Matisse, Maurice Utrillo, Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani. Composer William Walton also greatly benefited from his largesse (though he and Sitwell afterwards fell out) and Walton's cantata Belshazzar's Feast was written to Sitwell's libretto.

Sitwell published 2 books of poems: Argonaut and Juggernaut (1919) and At the House of Mrs Kinfoot (1921). In the mid-1920s he met David Horner, who was his lover and companion for most of his life.[1]

Baronetcy and autobiography[]

Sitwell succeeded to baronetcy after the death of his father, in 1943. He started an autobiography that ran to 4 volumes: Left Hand, Right Hand (1943), The Scarlet Tree (1946), Great Morning (1948) and Laughter in the Next Room (1949). Writing in The Adelphi, George Orwell declared that, " although the range they cover is narrow, [they] must be among the best autobiographies of our time.' [2] Sitwell's autobiography was followed by a collection of essays about various people he had known, Noble Essences: A Book of Characters (1950), and a postscript, Tales my Father Taught Me (1962).

Sitwell was a friend of Queen Elizabeth, the wife of King George VI. At the time of the abdication of King Edward VIII]] he wrote a poem, "Rat Week", attacking those supposed friends of the King who deserted him when his alliance with Mrs. Simpson became common knowledge in England. This was published anonymously and caused some scandal. The manuscript is in the library of Eton College).

Sitwell campaigned for the preservation of Georgian buildings and was responsible for saving Sutton Scarsdale Hall, now owned by English Heritage. He was an early and active member of the Georgian Group.

He also had an interest in the paranormal and joined the Ghost Club, which at the time was being relaunched as a dinner society dedicated to discussing paranormal occurrences and topics.

Death[]

Sitwell suffered from Parkinson's disease from the 1950s; by the mid-1960s this condition had become so severe that he needed to abandon writing. He died in Italy, at Montegufoni, a castle near Florence which his father had bought derelict in 1909 and restored as his personal residence. The castle was left to his nephew, Reresby; most of his money was left to Horner. Sitwell was buried in the Cimitero Evangelico degli Allori in Florence.

Writing[]

Sitwell's debut work of fiction, Triple Fugue, was published in 1924, and visits to Italy and Germany produced Discursions on Travel, Art and Life (1925). His debut novel, Before the Bombardment (1926), set in an out-of-season hotel, was well reviewed – Ralph Straus writing for Bystander magazine called it 'a nearly flawless piece of satirical writing', and Beverley Nichols praised 'the richness of its beauty and wit'.[3]

His subsequent novel, The Man Who Lost Himself, (1929) was an altogether different affair and did not receive the same critical acclaim. However, for Osbert Sitwell it was an attempt to take further the techniques that he had experimented with in his début, and he ventured to explain this in a challenging sentence in his Preface when he said: "Convinced that movement is not in itself enough, that no particular action or sequence of actions is in itself of sufficient concern to dare lay claim to the intelligent attention of the reader, that adventures of the mind and soul are more interesting, because more mysterious, than those of the body, and yet that, on the other hand, the essence does not reside to any much greater degree in the tangle of reason, unreason, and previous history, in which each action, event and thought is founded, but is to be discovered, rather, in that balance, so difficult to achieve, which lies between them, he has attempted to write a book which might best be described as a Novel of Reasoned Action".[4]

Re-edited over three quarters of a century after its initial publication, The Man Who Lost Himself has found new popularity as an idiosyncratic mystery novel.

Sitwell, sure in himself of the techniques he was exercising, went on to write several further novels, including Miracle on Sinai (1934) and Those Were the Days (1937) neither of which received the same glowing reviews as his first. A collection of short stories Open the Door (1940), his fifth novel A Place of One's Own (1940), his Selected Poems (1943) and a book of essays Sing High, Sing Low (1944) were reasonably well received. The Four Continents (1951) is a book of travel, reminiscence and observation.

The sometimes acidic diarist James Agate commented on Sitwell after a drinking session on 3 June 1932, in Ego, volume 1, "There is something self-satisfied and having-to-do-with-the-Bourbons about him which is annoying, though there is also something of the crowned-head consciousness which is disarming".

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Argonaut and Juggernaut. London: Chatto & Windus, 1919; New York: Knopf, 1920.

- Out of the Flame. London: Grant Richards, 1923.

- England Reclaimed: A book of eclogues. London: Duckworth, 1927; New York: George Doran, 1928.

- Collected Satires and Poems. London: Duckworth, 1931; New York: AMS Press, 1976.

- Mrs. Kimber. London: Macmillan, 1937.

- Selected Poems: Old and new. London: Duckworth, 1943; New York: AMS Press, 1976.

- England Reclaimed, and other poems. Boston: Little, Brown, 1943.

- On the Continent: A book of inguilinics. London: Macmillan, 1947.

- Four Songs of the Italian Earth. London & Pawlet, VT: Banyan Press, 1948.

- Demos the Emperor: A secular oratorio. London: Macmillan, 1949.

- Wrack at Tidesend: A book of balnearics. London: Duckworth, 1952.

- Poems about People; or, England reclaimed. London: Hutchinson, 1965.

Play[]

- All at Sea: A social tragedy in three acts for first-class passengers only (with Sacheverell Sitwell. London: Duckworth, 1927; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1927.

Novels[]

- Before the Bombardment. London: Duckworth, 1926; New York: Doran, 1926.

- The Man Who Lost Himself. London: Duckworth, 1929; New York: Coward-McCann, 1930.

- Miracle on Sinai: A satirical novel. London: Duckworth, 1933; New York: Holt, 1933.

- Those Were the Days: Panorama with figures. London: Macmillan, 1938.

- A Place of One's Own. London: Macmillan, 1941.

Short fiction[]

- Triple Fugue. London: Grant Richards, 1924; New York: Doran, 1924.

- Dumb-Animal, and other stories. London: Duckworth, 1930; Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1931.

- Open the Door! A volume of stories. London: Macmillan, 1941; New York: Smith & Durrell, 1941.

- The True Story of Dick Whittington: A Christmas story for cat lovers. London: Home & Van Thai, 1945.

- Alive, Alive, Oh!, and other stories. London: Pan, 1947.

- Death of a God, and other stories. London: Macmillan, 1949.

- Collected Stories. London: Duckworth, 1953; New York: Harper, 1953.

Non-fiction[]

- The Winstonburg Line: Three satires. London: Hendersons, 1919.

- Who Killed Cock-Robin? Remarks on poetry, on its criticism, and, as a sad warning, the story of Eunuch Arden. London: C.W. Daniel, 1921.

- Catalogue of an Exhibition of Italian Art of the Seventeenth Century. London: privately published for the Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1925.

- Discursions on Travel, Art, and Life. London: Grant Richards, 1925; New York: Doran, 1925.

- The People's Album of London Statues. London: Duckworth, 1928.

- Three-Quarter Length Portrait of Michael Arlen. London: Heinemann / Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, 1931.

- Dickens. London: Chatto & Windus, 1932.

- Winters of Content: More discursions on travel, art, and life. London: Duckworth, 1932; Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1932.

- Brighton (with Margaret Barton). London: Faber, 1935; Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1935.

- Penny Foolish: A book of tirades and panegyrics. London: Macmillan, 1935; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1967.

- Trio: Dissertations on some aspects of national genius (with Edith Sitwell & Sacheverell Sitwell). London: Macmillan, 1938.

- Escape with Me! An oriental sketch book. London: Macmillan, 1939; New York: Harrison-Hilton, 1940.

- Sing High! Sing Low! (essays). London: Macmillan, 1944.

- A Letter to My Son. London: Home & Van Thai, 1944.

- The Novels of George Meredith, and Some notes on the English novel. London: Oxford University Press, 1947.

- The Four Continents: Being more discursions on travel, art & life (illustrated by Daniel Maloney). London: Macmillan, 1954; New York: Harper, 1954.

- Pound Wise (essays). London: Hutchinson, 1963; Boston: Little, Brown, 1963.

- Queen Mary, and others. London: M. Joseph, 1974; New York: John Day, 1974.

- Rat Week: An essay on the abdication. London: M. Joseph, 1986.

Autobiography[]

- Left Hand! Right Hand!. Boston: Little, Brown, 1944.

- published in UK as Left Hand! Right Hand: An autobiography. Volume I: The Cruel Month. London: Macmillan, 1945.

- The Scarlet Tree. London: Macmillan, 1946; Boston: Little, Brown, 1946.

- Great Morning. London: Macmillan, 1947; Boston: Little, Brown, 1947.

- Laughter in the Next Room. Boston: Little, Brown, 1948; Toronto: Macmillan, 1948; London: Macmillan, 1949.

- Noble Essences ; or, Courteous revelations: Being a book of characters and the fifth and last volume of Left hand, right hand! An autobiography. London: Macmillan, 1950

- printed in U.S. as Noble Essences: A book of characters. Boston: Little, Brown, 1950; New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1950.

- Tales My Father Taught Me: An evocation of extravagant episodes. London: Hutchinson, 1962; Boston: Little, Brown, 1962.

Juvenile[]

- Fee Fi Fo Fum: A book of fairy stories. London: Macmillan, 1950.

Edited[]

- Georgiana Caroline Sitwell Swinton & Florence Alice Sitwell, Two Generations. London: Macmillan, 1940.

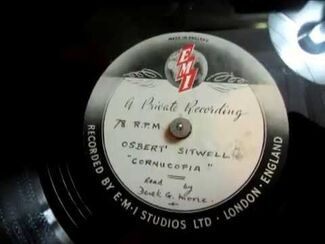

Cornucopia - Osbert Sitwell - Poetry Recitation - Derek G Moore - Private record

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[5]

Audio / video[]

- Osbert Sitwell: Reading from his poetry (LP). New York: Caedmon, 1953.[5]

See also[]

References[]

Fonds[]

- Osbert Sitwell Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center

Notes[]

- ↑ Pearson, John (1978), Façades: Edith, Osbert, and Sacheverell Sitwell, Macmillan

- ↑ The Adelphi, July–September 1948, reprinted in Orwell:Collected Works, It Is What I Think, p.398

- ↑ Quotes from thumbnail publicity for the Oxford University Press edition of the novel, introduced by Victoria Glendinning.

- ↑ Author's Preface, 1929 - The Man Who Lost Himself. LTMI Ed., 2007. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Search results = au:Osbert Sitwell, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Feb. 19, 2015.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Orpheus"

- Osbert Sitwell in Modern British Poetry: "The Blind Pedlar,"Progress"

- Sitwell in Poetry: A magazine of verse, 1912-1922: "Mrs. Freudenthal Consults the Witch of Endor," "Dead Man's Wood," "Maxixe"

- Sir Osbert Sitwell at AllPoetry (9 poems)

- Audio / video

- Books

- Osbert Sitwell at Amazon.com

- About

- Sir Osbert Sitwell, 5th baronet in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- The Sitwells at Making Britain

- Prose and poetry - Sir Osbert Sitwell at FirstWorldWar.com

- "Not a Very Loud Voice:" review of Osbert Sitwell by Philip Ziegler

|