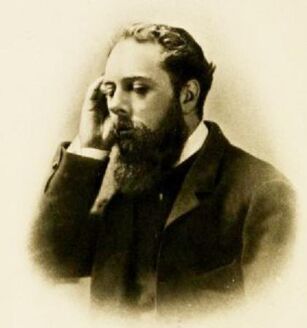

Philip Bourke Marston (1850-1887). Courtesy Musikinesis.

Philip Bourke Marston (13 August 1850 - 13 February 1887) was an English poet and story writer.

Life[]

Overview[]

Marston, born in London, lost his sight at the age of 3. His poems, Song-tide, All in All, and Wind-voices bear, in their sadness, the impress of this affliction, and of a long series of bereavements. He was the friend of Rossetti and of Swinburne, the latter of whom has written a sonnet to his memory.[1]

Youth and education[]

Marston was born in London, the son of John Westland Marston. Philip James Bailey and Dinah Maria Mulock were his godparents, and the most popular of the latter's short poems, "Philip, my King," is addressed to him.[2]

When only 3 years old he went blind, due to the administration of belladonna as a prophylactic against scarlet fever, aggravated, it was thought, by an accidental blow. The loss of vision was not for many years so complete as to prevent him from seeing, in his own words, "the tree-boughs waving in the wind, the pageant of sunset in the west, and the glimmer of a fire upon the hearth;" and this dim, imperfect perception must have been more stimulating to the imagination than a condition of either perfect sight or total blindness.[2]

He indulged, like Hartley Coleridge, in a consecutive series of imaginary adventures and in the reveries called up by music, for which he exhibited the usual fondness of the blind. The inevitable effect was to excite the ideal side of a powerful mind into premature and excessive activity while discouraging reflection and mental discipline, to which he remained a stranger all his life.[2]

Adult life[]

Philip Bourke Maston (1850-1887). Courtesy Poetry Atlas.

His extraordinary gifts of verbal expression and melody were soon manifested in poems of remarkable merit for his years, and displaying a power of delineating the aspects of nature which, his affliction considered, seemed almost incomprehensible. These efforts met full recognition from the brilliant literary circle then gathered around his father, and he was intensely happy for a time in the affection of Mary Nesbit.[2]

The death of his betrothed from rapid consumption, in November 1871, absolutely prostrated him, and was the precursor of a series of calamities which might well excuse the morbid element in his views of life and nature.[2]

In 1874, a friend, Oliver Madox Brown, died after a short and unforeseen illness. In 1878 Marston was bereaved with equal suddenness of his sister Cicely, to whom one of his most beautiful poems is addressed, and whose devotion to him was absolute. His surviving sister, Eleanor, died early in the following year; her husband, Arthur O'Shaughnessy, followed shortly.[2]

In 1882, the death of his chief poetic ally and inspirer, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was followed closely by that of another kindred spirit, James Thomson, who was carried dying from his blind friend's rooms, where he had sought refuge from his latest miseries early in June of the same year.[3] Rossetti's kindly appreciation of his disciple, and like generosity on the part of Swinburne, had formed the main solace of Marston's infelicitous life.[4]

Marston's sight had also become extinct, and his pecuniary means were greatly diminished.[4] It is not surprising that his verse became increasingly sorrowful and melancholy. The idylls of flower-life, such as the early and very beautiful The Rose and the Wind, were succeeded by dreams of sleep and the repose of death. These qualities and gradations of feeling are traceable through his 3 published collections, Song-tide (1871), All in All (1873) and Wind-voices (1883).[3]

Marston's own generous and open disposition procured him many warm friends, among them his subsequent editors and biographers, American poet Louise Chandler Moulton and William Sharp. The former was especially instrumental in finding a public in America for the numerous short stories by which the author partly supported himself.[4] His popularity in America far exceeded that in his own country.[3]

Marston's relations with his father also were singularly affectionate; he usually accompanied him in a summer tour, and it was an one of these excursions that he received the sunstroke which accelerated the paralytic attack that befell him early in 1887.[4] His health had showed signs of collapse from 1883; in January 1887 he lost his voice, and suffered intensely from the failure to make himself understood. He died on the 13th of February 1887.[3]

Writing[]

The sadness of his poetry is no subject for surprise, and is chiefly to be regretted as a barrier in the way of a literary renown which might have stood much higher under happier circumstances. The 3 volumes of poetry published in his lifetime abound with beautiful thoughts expressed in beautiful language, but soon become tedious from the monotony, not merely of sentiment, but of diction and poetical form.[4]

The sonnet was undoubtedly best adapted to render his usual vein of feeling; and that or allied forms of verse became so habitual with him that he seemed to experience a difficulty in casting his thoughts into any other mould. Supreme excellence, however, is at once so indispensable in the sonnet and so difficult to attain, that although Marston did not always fall short of it, the greater part of his work in this department can only be classed as 2nd-rate. He also suffered from the too faithful following, degenerating into imitation, of a greater master, Rossetti.[4]

Critical introduction[]

As was inevitable with men who, endowed with great energy, instead of being engaged as it were in some morning adventure of the world looked back regretfully to a long-past age of clean beauty across a civilization that had violated all in life that they cherished, there was in the temper of the Pre-Raphaelite poets a deep strain of wistfulness which is rarely found in great poetry, and is a different thing from the tragic intensity that is found there commonly enough. Even Keats, whose work is as poignant as that of any poet, leaves us with the impression that in creation, even the creation of tragic beauty, he was possessed entirely with the artist’s joy, while in reading the great Pre-Raphaelites we feel always, touching all their splendid exuberance, a tremulous sadness: some touch of inescapable regret.

The individual genius of Rossetti, Swinburne, Morris, was more than equal to disciplining this plaintiveness until it became no more than an added loveliness in their work, which remained positive and quick with assertion. With lesser poets, however, authentic though they were, who came under this same influence, made more intimate by the example of these masters themselves, there was a likelihood of this plaintiveness becoming over-insistent; and this is what happened, until the poetic emotion became diluted, the values of life were lowered a little, and there developed the delicate and fragrant but slightly insignificant decadent poetry of the '90s.

Philip Marston was among the most notable of the poets with whom this group began, and although in him poetry kept its high dignity, and it was not until a little later that it became fashionable to write of life as a pack of cards or a Chinese lantern, the over-prevalence of plaintiveness is already clearly marked in his verse. It is not that his work is the reflection of a life that was almost epic in its sorrows. Marston was afflicted with a wrath that was terrible as some visitation of the Old Testament, but while remorseless personal misfortune emphasized the natural attitude to life which he inherited from his masters, it could not produce the precise quality of which we speak in his poetry. This was, rather, the product of an imagination that was never quite of the highest intensity. His lamentable life, indeed, far from inevitably influencing his work in this manner, might have touched it to a magnificent though profound gloom, as such misfortune has done with other poets. But it is as though his griefs had struck beyond his happiness and had impaired his poetic energy, so that he was unable fully to control, as the greater poets of his time controlled, an emotion that in its place may even be admirable in poetry, but which, out of its place, makes for enervation.

And it is exactly in this way that Marston’s work suffered. His natural gifts were fine ones, and he cultivated them with splendid devotion. To the expression of an extremely delicate susceptibility and sometimes of a thrilling passion, he brought a just and varied sense of word-values and an artistic discretion that rarely failed him, so that his work is hardly ever without a distinct and personal beauty. But, also, it is hardly ever bracing, and poetry, even in its forlorn moods, should brace.

This same central infirmity kept him, in most of his poems, from achieving those radiant touches, living in the use of a word or the turn of a syllable, half chance and almost remote from reason, that so often makes the difference between a poem in which it is difficult or impossible to find a flaw, and one that is of manifest excellence. This is strikingly so in most of Marston’s sonnets, of which he wrote a large number. In reading through them we find great technical sureness; more than that, we are constantly aware of a fine poetic temper, that keeps us securely above any feeling of tediousness, and we gladly allow a sweet musical movement. But it is only very rarely that we are stirred to the delighted admiration that greets those fortunate strokes that are a poet’s chief glory. We feel constantly that Marston, charming poet as he was, was within a phrase of being a top-rank one.

His best poems are certain of the sonnets and a few voluptuously passionate love-poems in which he attained an intensity that was far more admirable and of far more durable worth than the rather trivial prettiness of "The Rose and the Wind" and the other Garden Fancies through which the anthologies have made him most generally known. There is, too, a grave beauty in "The Old Churchyard of Bonchurch" and such lyrics as "From Far" that shows with what poetic dignity his spirit could work when most truly moved.[5]

Recognition[]

His memory was honored by a fine elegy from Swinburne, printed in the Fortnightly Review for January 1891,[4] beginning “The days of a man are threescore years and ten.” He was also commemorated in Thomas Gordon Hake's “Blind Boy."[3]

2 posthumous collections of his poems were published by Moulton, under the titles of Garden Secrets (1887) and A Last Harvest (1891). She also published in 1892 The Collected Poems of Philip Bourke Marston, with Biographical Sketch and Portrait.[4]

There is an intimate sketch of Marston by a friend, Coulson Kernahan, in Sorrow and Song, 1894, 127.[3]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Song-tide, and other poems. London: Ellis & Green, 1871; Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1871; London: Chatto & Windus, 1874.

- All in All: Poems and sonnets. London: Chatto & Windus, 1875.

- Wind-voices. London: E. Stock, 1883; Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1883.

- Garden Secrets (edited by Louise Chandler Moulton). Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1887.

- Song-tide: Poems and lyrics of love's joy and sorrow (edited by William Sharp). London: Walter Scott, 1888.

- A Last Harvest: Lyrics and sonnets from the book of love (edited by Louise Chandler Moulton). London: Elkin Mathews, 1891.

- Collected Poems (edited by Louise Chandler Moulton). London: London : Ward, Lock, Bowden, 1892; Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1892; New York: AMS Press, 1973.

Short fiction[]

- For a Song's Sake, and other stories. London: Walter Scott, 1888.

Anthologized[]

- Pre-Raphaelite Writing: An anthology (edited by Derek Stanford). London: Dent / Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield, 1973.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[6]

See also[]

Garden Fairies by Philip Bourke Marston Clarica Poetry Moment

References[]

Garnett, Richard (1893) "Marston, Philip Bourke" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 36 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 260-261. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 22, 2017.

- Coulson Kernahan, Sorrow and Song. Philadelphia: 1894.

Seccombe, Thomas (1911). "Marston, Philip Bourke". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 777..

- William Sharp, Papers Critical and Reminiscent. New York: 1912.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Marston, Philip Bourke," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 260. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 11, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Garnett, 260.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Seccombe, 777.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Garnett, 261.

- ↑ from John Drinkwater, "Critical Introduction: Philip Bourke Marston (1850–1887)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 28, 2016.

- ↑ Search results = au:Philip Bourke Marston, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Mar. 28, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- "The Old Churchyard of Bonchurch" at Poetry Atlas

- 2 poems by Martson: "A July Day, "After Summer"

- Philip Bourke Marston at PoemHunter (3 poems)

- Marston in The English Poets: An anthology: "Inseparable," "Persitent Music," "The First Kiss," "Bridal Eve," "The Old Churchyard of Bonchurch," "From Far"

- Philip Bourke Marston at Poetry Nook (8 poems)

- Marston in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "A Greeting," "A Vain Wish," "Love's Music," "The Rose and the Wind," "How My Song of Her Began," "The Old Churchyard of Bonchurch," "Garden Fairies," "Love and Music," "No Death," "At the Last," "Her Pity," "After Summer," "To the Spirit of Poetry," "If You Were Here," "At Last"

- Audio / video

- Philip Bourke Marston poems at YouTube

- Books

- Martson, Philip Bourke (1850-1887 at Internet Archive

- Philip Bourke Marston at Amazon.com

- About

- Marston, Philip Bourke at Digital Victorian Periodical Poetry

- Expectations of Darkness: The "Blind Poet" P.B. Marston at The Free Library

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Marston, Philip Bourke

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at Marston, Philip Bourke

|