Robert Browning (1812-1889), from Poems of Robert Browning, London & New York: Henry Frowde for Oxford Univrsity Press, 1912. Courtesy Internet Archive.

| Robert Browning | |

|---|---|

| Born |

7 May 1812 Camberwell, London, England |

| Died |

12 Decemmber 1889 (aged 77) Venice, Italy |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Notable work(s) | The Pied Piper of Hamelin, Porphyria's Lover, The Ring and the Book, Men and Women, My Last Duchess |

|

Influenced

| |

|

| |

| Signature | File:Robert Browning Signature.svg |

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 - 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of dramatic verse, especially dramatic monologues, made him a foremost Victorian poet.

Life[]

Overview[]

Browning, the only son of Robert Browning (a man of fine intellect and character, who worked in the Bank of England), was born in Camberwell. In his childhood he was distinguished by his love of poetry and natural history. After being at private schools and showing a dislike to school life, he was educated by a tutor, and later studied Greek at University College London. His first publication was Pauline, which appeared anonymously in 1833, but attracted little attention. Paracelsus in 1835, though having no general popularity, gained the notice of Carlyle, Wordsworth, and other men of letters, and gave him a reputation as a poet of distinguished promise. 2 years later his drama of Stratford was performed by his friend Macready and Helen Faucit, and in 1840 the most difficult and obscure of his works, Sordello, appeared; but, except with a select few, did little to increase his reputation. In 1846 he married poet Elizabeth Barrett, a union of ideal happiness. Thereafter his home until his wife's death in 1861 was in Italy, chiefly at Florence. After his wife's death he returned to England, paying, however, frequent visits to Italy.[1]

To the great majority of readers, probably, he is best known by some of his short poems, such as, to name a few, "Rabbi Ben Ezra," "How they brought the good News to Aix," "Evelyn Hope," "The Pied Piper of Hammelin," "A Grammarian's Funeral," "A Death in the Desert." It was long before England recognised that in Browning she had received one of the greatest of her poets, and the causes of this lie on the surface. His subjects were often recondite and lay beyond the ken and sympathy of the great bulk of readers; and owing, partly to the subtle links connecting the ideas and partly to his often extremely condensed and rugged expression, the treatment of them was not seldom difficult and obscure. Consequently for long he appealed to a somewhat narrow circle. As time went on, however, and work after work was added, the circle widened, and the marvellous depth and variety of thought and intensity of feeling told with increasing force. Societies began to be formed for the study of the poet's work. Critics became more and more appreciative, and he at last reaped the harvest of admiration and honour which was his due. Many distinctions came to him. He died in the house of his son at Venice, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.[1]

Youth[]

Browning was born at Southampton Street, Camberwell. "He was a handsome, vigorous, fearless child, and soon developed an unresting activity and a fiery temper" (Mrs. Orr). He was keenly susceptible, from earliest infancy, to music, poetry, and painting. At 2 years and 3 months he painted (in lead-pencil and black-currant jam-juice) a composition of a cottage and rocks, which was thought a masterpiece. So turbulent was he and destructive that he was sent, a mere infant, to the day-school of a dame, who has the credit of having divined his intellect. One of the first books which influenced him was Croxall's Fables in verse, and he soon began to make rhymes, and a little later plays. From a very early age he began to devour the volumes in his father's well-stocked library.

About 1824 he had completed a little volume of verses, called Incondita, for which he endeavoured in vain to find a publisher, and it was destroyed. It had been shown, however, to Miss Sarah Flower, afterwards Mrs. Adams, who made a copy of it; this copy, 50 years afterwards, fell into the hands of Browning himself, who destroyed it. He later said that these verses were servile imitations of Lord Byron, who was at that time still alive; and that their only merit was their mellifluous smoothness.

Of Miss Eliza Flower (elder sister of Sarah Flower), his earliest literary friend, Browning always spoke with deep emotion. Although she was 9 years his senior, he regarded her with tender boyish sentiment, and she is believed to have inspired Pauline. In 1825, in his 14th year, a complete revolution was made in the boy's attitude to literature by his becoming acquainted with the poems of Shelley and Keats, which his mother bought for him in their original editions. He was at this time at the school of the Rev. Thomas Ready in Peckham.

In 1826 the question of his education was seriously raised, and it was decided that he should be sent neither to a public school nor ultimately to a university. In later years the poet regretted this decision, which, however, was probably not unfavorable to his idiosyncrasy. He was taught at home by a tutor; his training was made to include "music, singing, dancing, riding, boxing, and fencing." He became an adept at some of these, in particular a graceful and intrepid rider. From 14 to 16 he was inclined to believe that musical composition would be the art in which he might excel, and he wrote a number of settings for songs; these he afterwards destroyed. At his father's express wish, his education was definitely literary.

In 1829-1830, for a very short time, he attended the Greek class of Professor George Long at London University, afterwards University College, London. His aunt, Mrs. Silverthorne, greatly encouraged his father in giving a lettered character to Robert's training. He now formed the acquaintance of 2 young men of adventurous spirit, each destined to become distinguished, Joseph Arnould and Alfred Domett; both then lived at Camberwell. Domett early in his career went out to New Zealand, in circumstances the suddenness and romance of which suggested to Browning his poem of "Waring." To Domett also "The Guardian Angel" is dedicated, and he remained through life a steadfast friend of the poet.

While he was at University College, his father asked him what he intended to be. The young man replied by asking if his sister would be sufficiently provided for if he adopted no business or profession. The answer was that she would be. The poet then suggested that it would be better for him "to see life in the best sense, and cultivate the powers of his mind, than to shackle himself in the very outset of his career by a laborious training, foreign to that aim." "In short, Robert, your design is to be a poet?" He admitted it; and his father at once acquiesced.

Early career[]

In October 1832 Robert was already engaged upon his first completed work, Pauline. Mrs. Silverthorne paid for it to be printed, and the little volume appeared, anonymously, in January 1833. The poet sent a copy to W.J. Fox, with a letter in which he described himself as "an oddish sort of boy, who had the honour of being introduced to you at Hackney some years back" by Sarah Flower Adams. Fox reviewed Pauline with very great warmth in the Monthly Repository, and it fell also under the favourable notice of Allan Cunningham. J.S. Mill read and enthusiastically admired it, but had no opportunity of giving it public praise. With these exceptions Pauline fell absolutely still-born from the press.

Browning's life during the next 2 years is very obscure. He was still occupied with certain religious speculations. In the winter of 1833-4, as the guest of Mr. Benckhausen, the Russian consul-general, he spent 3 months in St. Petersburg, an experience which had a vivid effect on the awakening of his poetic faculties. At St. Petersburg he wrote "Porphyria's Lover" and "Johannes Agricola," both of which were printed in the Monthly Repository in 1836. These are the earliest specimens of Browning's dramatico-lyrical poetry which we possess, and their maturity of style is remarkable. A sonnet, 'Eyes calm beside thee,' is dated 17 Aug;. 1834.

In the early part of 1834 he paid his first visit to Italy, and saw Venice and Asolo. Having just returned from his first visit to Venice, he used to illustrate his glowing descriptions of its beauties, the palaces, the sunsets, the moonrises, by a most original kind of etching 'on smoked note-paper (Mrs. Bridell-Fox). In the winter of 1834 he was absorbed in the composition of 'Paracelsus,' which was completed in March 1835. Fox helped him to find a publisher, Effingham Wilson. 'Paracelsus' was dedicated to the Comte Amadée de Ripert-Monclar (b. 1808), a young French royalist, who had suggested the subject to Browning.

John Forster, who had just come up to London, wrote a careful and enthusiastic review of 'Paracelsus' in the 'Examiner,' and this led to his friendship with Browning. The press in general took no notice of this poem, but curiosity began to awaken among lovers of poetry. 'Paracelsus' introduced Browning to Carlyle, Talfourd, Landor, Home, Monckton Milnes, Barry Cornwall, Mary Mitford, Leigh Hunt, and eventually to Wordsworth and Dickens. About 1836 the Browning family moved from Camberwell to Hatcham, to a much larger and more convenient house, where the picturesque domestic life of the poet was developed. In November W. J. Fox asked him to dinner to meet Macready, who was already prepared to admire 'Paracelsus;' he entered in his famous diary 'The writer can scarcely fail to be a leading spirit of his time.' Browning saw the new year, 1836, in at Macready's house in Elstree, and met Forster for the first time in the coach on the way thither. Macready urged him to write for the stage, and in February Browning proposed a tragedy of 'Narses.' This came to nothing, but after the supper to celebrate the success of Talfourd's 'Ion' (26 May 1836), Macready said, 'Write a play, Browning, and keep me from going to America. What do you say to a drama on Strafford?' The play, however, was not completed for nearly another year. On 1 May 1837 'Strafford' was published and produced at Covent Garden Theatre. It was played by Macready and Helen Faucit, but it only ran for five nights. Vandenhoff, who had played the part of Pym with great indifference, cavalierly declined to act any more. For the next two or three years Browning lived very quietly at Hatcham, writing under the rose trees of the large garden, riding on 'York,' his horse, and steeping himself in all literature, modern and ancient, English and exotic. His labours gradually concentrated themselves on a long narrative poem, historical and philosophical, in which he recounted the entire life of a mediæval minstrel. He had become terrified at what he thought a tendency to diffuseness in his expression, and consequently 'Sordello' is the most tightly compressed and abstrusely dark of all his writings. He was partly aware himself of its excessive density ; the present writer (in 1875) saw him take up a copy of the first edition, and say, with a grimace, 'Ah! the entirely unintelligible "Sordello."' It was partly written in Italy, for which country Browning started at Easter, 1838. He went to Trieste in a merchant ship, to Venice, Asolo, the Euganean Hills, Padua, back to Venice; then by Verona and Salzburg to the Rhine, and so home. On the outward voyage he wrote 'How they brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix,' and many of his best lyrics belong to this summer of 1838. In 1839 he finished 'Sordello' and began the tragedies 'King Victor and King Charles' and 'Mansoor the Hierophant,' and formed the acquaintance of his father's old schoolfellow, John Kenyon [q. v.] In 1840 he composed a tragedy of 'Hippolytus and Aricia,' of which all that has been preserved is the prologue spoken by Artemis.

'Sordello' was published in 1840, and was received with mockery by the critics and with indifference by the public. Even those who had welcomed 'Paracelsus' most warmly looked askance at this congeries of mystifications, as it seemed to them. Browning was not in the least discouraged, although, as Mrs. Orr has said, 'he was now entering on a period of general neglect which covered nearly twenty years of his life.' The two tragedies were now completed, the title of 'Mansoor' being changed to 'The Return of the Druses.' Edward Moxon proposed to Browning that he sliould print his poems as pamphlets, each to form a separate brochure of just one sheet, sixteen pages in double columns, the entire cost of each not to exceed twelve or fifteen pounds. In this fashion were produced the series of 'Bells and Pomegranates,' eight numbers of which appeared successively between 1841 and 1846. Of the business relations between Browning and Moxon the poet gave the following relation in 1874, in a letter still unpublished, addressed to F. Locker Lampson: 'He [Moxon] printed, on nine occasions, nine poems of mine, wholly at my expense : that is, he printed them and, subtracting the very moderate returns, sent me in, duly, the bill of the remainder of expense. . . . Moxon was kind and civil, made no profit by me, I am sure, and never tried to help me to any, he would have assured you.'

'Pippa Passes' opened the series of 'Bells and Pomegranates' in 1841; No. ii. was 'King Victor and King Charles,' 1842; No. iii. 'Dramatic Lyrics,' 1842; No. iv. 'The Return of the Druses,' 1843 ; No. v. 'A Blot in the 'Scutcheon,' 1843; No. vi. 'Colombo's Birthday,' 1844; No. vii. 'Dramatic Romances and Lyrics,' 1845; and No. viii. 'Luria' and 'A Soul's Tragedy,' 1846. In a suppressed 'note of explanation' Browning stated that by the title 'Bells and Pomegranates' he meant 'to indicate an endeavour towards something like an alternation, or mixture, of music with discoursing, sound with sense, poetry with thought.' Of the composition of these works the following facts have been preserved. 'Pippa Passes' was the result of the sudden image of a figure walking alone through life, which came to Browning in a wood near Dulwich. 'Dramatic Lyrics' contained the poem of 'The Pied Piper of Hamelin,' which was written in May 1842 to amuse Macready's little son William, who made some illustrations for it which the poet preserved. At the same time was written 'Crescentius,' which was not printed until 1890. 'The Lost Leader' was suggested by Wordsworth's 'abandonment of liberalism at an unlucky juncture; 'but Browning resisted strenuously the notion that this poem was a 'portrait' of Wordsworth. In 1844 and 1845 Browning contributed six important poems to 'Hood's Magazine;' all these they included 'The Tomb at St. Praxed's' and 'The Flight of the Duchess' — were reprinted in 'Bells and Pomegranates.' The play, 'A Blot in the 'Scutcheon,' was written at the desire of Macready, and was first performed at Drury Lane on 11 Feb. 1843. It had been read in manuscript by Charles Dickens, who wrote, 'It has thrown me into a perfect passion of sorrow, and I swear it is a tragedy that must be played, and must be played, moreover, by Macready.' For some reason Forster concealed this enthusiastic judgment of Dickens from Browning, and probably from Macready. The latter did not act in it, and treated it with contumely. Browning gave the leading part to Phelps, and the heroine was played by Helen Faucit. 'The Blot in the 'Scutcheon,' though well received, was 'underacted' and had but a short run. There followed a quarrel between the poet and Macready, who did not meet again till 1862. 'Colombe's Birthday' was read to the Keans on 10 March 1844, but as they wished to keep it by them until Easter, 1845, the poet took it away and printed it. It was not acted until 25 April 1853, when Helen Faucit and Barry Sullivan produced it at the Haymarket. About the same time it was performed at the Harvard Athenæum, Cambridge, U.S.A.

In the autumn of 1844 Browning set out on his third journey to Italy, taking ship direct for Naples. He formed the acquaintance of a cultivated young Neapolitan, named Scotti, with whom he travelled to Rome. At Leghorn Browning visited E..T. Trelawney. The only definite relic of this journey which survives is a shell, 'picked up on one of the Syren Isles, October 4, 1844,' but its impressions are embodied in 'The Englishman in Italy,' 'Home Thoughts from Abroad,' and other romances and lyrics. Browning was now at the very height of his genius. It was through Kenyon that Browning first became acquainted with Elizabeth Barrett Moulton Barrett, who was already celebrated as a poet, and had, indeed, achieved a far wider reputation than Browning. Miss Barrett was the cousin of Kenyon; a confirmed invalid, she saw no one and never left the house. She was an admirer of Browning's poems; he, on the other hand, first read hers in the course of the opening week of 1845, although he had become aware that she was a great poet. She was six years older than he, but looked much younger than her age. He was induced to write to her, and his first letter, addressed from Hatcham on 10 Jan. 1845 to Miss Barrett, at 50 Wimpole Street, is a declaration of passion: 'I love your books, and I love you too.' She replied, less gushingly, but with warmest friendship, and in a few days they stood, without quite realising it at first, on the footing of lovers. Their earliest meeting, however, took place at Wimpole Street, in the afternoon of Tuesday, 20 May, 1845. Miss Barrett received Browning prone on her sofa, in a partly darkened room; she 'instantly inspired him with a passionate admiration.' They corresponded with such fulness that their missives caught one another by the heels; letters full of literature and tenderness and passion; in the course of which he soon begged her to allow him to devote his life to her care. She withdrew, but he persisted, and each time her denial grew fainter. He visited her three times a week, and these visits were successfully concealed from her father, a man of strange eccentricity and selfishness, who thought that the lives of all his children should be exclusively dedicated to himself, and who forbade any of them to think of marriage. In the whole matter the conduct of Browning, though hazardous and involving great moral courage, can only be considered strictly honourable and right. The happiness, and even perhaps the life, of the invalid depended upon her leaving the hothouse in which she was imprisoned. Her father acted as a mere tyrant, and the only alternatives were that Elizabeth should die in her prison or should escape from it with the man she loved. All Browning's preparations were undertaken with delicate forethought. On 12 Sept. 1846, in company with Wilson, her maid. Miss Barrett left Wimpole Street, took a fly from a cab-stand in Marylebone, and drove to St. Pancras Church, where they were privately married. She returned to her father's house; but on 19 Sept. (Saturday) she stole away at dinner-time with her maid and Flush, her dog. At Vauxhall Station Browning met her, and at 9 p.m. they left Southampton for Havre, and on the 20th were in Paris. In that city they found Mrs. Jameson, and in her company, a week later, started for Italy. They rested two days at Avignon, where, at the sources of Vaucluse, Browning lifted his wife through the 'chiare, frische e dolci acque,' and seated her on the rock where Petrarch had seen the vision of Laura. They passed by sea from Marseilles to Genoa. Early in October they reached Pisa, and settled there for the winter, taking rooms for six months in the Collegio Ferdinando. The health of Mrs. Browning bore the strain far better than could have been anticipated; indeed, the courageous step which the lovers had taken was completely justified; Mr. Barrett, however, continued implacable.

The poets lived with strict economy at Pisa, and Mrs. Browning benefited from the freedom and the beauty of Italy: 'I was never happy before in my life,' she wrote (5 Nov. 1846). Early in 1847 she showed Browning the sonnets she had written during their courtship, which she proposed to call 'Sonnets from the Bosnian.' To this Browning objected, 'No, not Bosnian — that means nothing — but "From the Portuguese"! They are Catarina's sonnets.' These were privately printed in 1847, and ultimately published in 1850; they form an invaluable record of the loves of two great poets. Their life at Pisa was 'such a quiet, silent life,' and by the spring of 1847 the health of Elizabeth Browning seemed entirely restored by her happiness and liberty. In April they left Pisa and reached Florence on the 20th, taking up their abode in the Via delle Belle Donne. They made a plan of going for several months, in July, to Vallambrosa, but they were 'ingloriously expelled' from the monastery at the end of five days. They had to return to Florence, and to rooms in the Palazzo Guidi, Via Maggio, the famous 'Casa Guidi.' Here also the life was most quiet: 'I can't make Robert go out for a single evening, not even to a concert, nor to hear a play of Alfleri's, yet we fill up our days with books and music, and a little writing has its share' (E.B.B. to Mary Mitford, 8 Dec. 1847).

Early in 1848 Browning began to prepare a collected edition of his poems. He proposed that Moxon should publish this at his own risk, but he declined; whereupon Browning made the same proposal to Chapman & Hall, or Forster did it for him, and they accepted. This edition appeared in two volumes in 1849, but contained only 'Bells and Pomegranates' and 'Paracelsus.' The Brownings had now been living in Florence, in furnished rooms, for more than a year, so they determined to set up a home for themselves. They took an apartment of 'six beautiful rooms and a kitchen, three of tliem quite palace rooms, and opening on a terrace' in the Casa Guidi. They saw few English visitors, and 'as to Italian society, one may as well take to longing for the evening star, it is so inaccessible' (l0 July 1848). In August they went to Fano, Ancona, Sinigaglia, Rimini, and Ravenna. In October Father Prout joined them for some weeks, and was a welcome apparition. 'The Blot on the 'Scutcheon' was revived this winter at Sadler's Wells, by Phelps, with success. On 9 March 1849 was born in Casa Guidi the poets' only child, Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, and a few days later Browning's mother died. Sorrow greatly depressed the poet at this time, and their position in Florence, in the disturbed state of Tuscany, was precarious. They stayed there, however, and in July moved merely to the Bagni di Lucca, for three months' respite from the heat. They took 'a sort of eagle's nest, the highest house of the highest of the three villages, at the heart of a hundred mountains, sung to continually by a rushing mountain stream.' Here Browning's spirits revived, and they enjoyed adventurous excursions into the mountains. In October they returned to Florence, During this winter Browning was engaged in composing 'Christmas Eve and Easter Day,' which was published in March 1850. They gradually saw more people — Lever, Margaret Fuller Ossoli, Kirkup, Greenough, Miss Isa Blagden. In September the Brownings went to Poggio al Vento, a villa two miles from Siena, for a few weeks. The following months, extremely quiet ones, were spent in Casa Guidi, the health of Elizabeth Browning not being quite so satisfactory as it had previously been since her marriage. On 2 May 1851 they started for Venice, where they spent a month; and then by Milan, Lucerne, and Strassburg to Paris, where they settled down for a few weeks.

At the end of July they crossed over to England, after an absence of nearly five years, and stayed until the end of September in lodgings at 26 Devonshire Street. They lived very quietly, but saw Carlyle, Forster, Fanny Kemble, Rogers, and Barry Cornwall. As Mr. Barrett refused all communication with them, in September Browning wrote 'a manly, true, straight- forward letter 'to his father-in-law, appealing for a conciliatory attitude; but he received a rude and insolent reply, enclosing, unopened, with the seals unbroken, all the letters which his daughter had written to him during the five years, and they settled, at the close of September, at 138 Avenue des Champs-Elysées; the political events in Paris interested them exceedingly. It was on this occasion that Carlyle travelled with them from London to Paris. They were received by Madame Mohl, and at her house met various celebrities. Browning attracted some curiosity, his poetry having been introduced to French readers for the first time in the August number of the 'Revue des Deux Mondes,' by Joseph Milsand. They walked out in the early morning of 2 Dec. while the coup d'état was in progress. In February 1852 Browning was induced to contribute a prose essay on Shelley to a volume of new letters by that poet, which Moxon was publishing; he did not know anything about the provenance of the letters, and the introduction was on Shelley in general. However, to his annoyance, it proved that Moxon was deceived; the letters were shown to be forgeries, and the book was immediately withdrawn. The Brownings saw George Sand (13 Feb.), and.Robert walked the whole length of the Tuileries Gardens with her on his arm (7 April); but missed, by tiresome accidents, Alfred de Musset and Victor Hugo.

At the end of June 1862 the Brownings returned to London, and took lodgings at 58 Welbeck Street. They went to see Kenyon at Wimbledon, and met Landor there. They saw, about this time, Ruskin, Patmore, Monckton Milnes, Kingsley, and Tennyson; and it is believed that in this year Browning's friendship with D. G. Rossetti began. Towards the middle of November 1852 the Brownings returned to Florence, which Robert found deadly dull after Paris — 'no life, no variety.' This winter Robert (afterwards the first earl) Lytton made their acquaintance, and became an intimate friend, and they saw Frederick Tennyson, and Power, the sculptor. On 25 April 1853 Browning's play, 'Colombe's Birthday,' was performed at the Hay market for the first time. From July to October 1853 they spent in their old haunt in the Casa Tolomei, Bagni di Lucca, and here Browning wrote 'In a Balcony,' and was 'working at a volume of lyrics.' After a few weeks in Florence the Brownings moved on (November 1853) to Rome, where they remained for six months, in the Via Bocca di Leone; here they saw Fanny Kemble, Thackeray, Mr. Aubrey de Vere, Lockhart (who said, 'I like Browning, he isn't at all like a damned literary man'), Leighton, and Ampere. They left Rome on 22 May, travelling back to Florence in a vettura. Money embarrassments kept them 'transfixed' at Florence through the summer, 'unable even to fly to the mountains,' but the heat proved bearable, and they lived 'a very tranquil and happy fourteen months on their own sofas and chairs, among their own nightingales and fireflies.'

This was a silent period in Browning's life; he was hardly writing anything new, but revising the old for 'Men and Women.' In February 1854 his poem 'The Twins' was privately printed for a bazaar. In July 1855 they left Italy, bringing with them the manuscripts of 'Men and Women' and of 'Aurora Leigh.' They went to 13 Dorset Street, where many friends visited them. It was here that, on 27 Sept., D. G. Rossetti made his famous drawing of Tennyson reading 'Maud' aloud. Here too was written the address to E.B.B., 'One Word More.' Soon after the publication of 'Men and Women' they went in October to Paris, lodging in great discomfort at 102 Rue de Grenelle, Faubourg St.-Germain. In December they moved to 3 Rue du Colisee, where they were happier. Browning was now engaged on an attempt to rewrite 'Sordello' in more intelligible form; this he presently abandoned. He had one of his very rare attacks of illness in April 1856, brought on partly by disinclination to take exercise. The poem of 'Ben Karshook's Wisdom,' which he excised from the proofs of 'Men and Women,' and which he never reprinted, appeared this year in 'The Keepsake' as 'May and Death' in 1857. Kenyon having offered them his London house, 39 Devonshire Place, they returned in June 1856 to England, but were called to the Isle of Wight in September by the dangerous illness of that beloved friend. He seemed to rally, and in October the Brownings left for Florence; Kenyon, however, died on 3 Dec. leaving large legacies to the Brownings. 'During his life his friendship had taken the practical form of allowing them 100l. a year, in order that they might be more free to follow their art for its own sake only, and in his will he left 6,500l. to Robert Browning and 4,500l. to Elizabeth Browning. These were the largest legacies in a very generous will — the fitting end to a life passed in acts of generosity and kindness' (F. G. Kenyon). The early part of 1857 was quietly spent in the Casa Guidi; but on 30 July the Brownings went, for the third time, to Bagni di Lucca. They were followed by Robert Lytton, who wished to be with them; but he arrived unwell, and was prostrated with gastric fever, through which Browning nursed him. The Brownings returned to Florence in the autumn, and the next twelve months were spent almost without an incident. But in July 1858 they went to Paris, where they stayed a fortnight at the Hotel Hyacinthe, Rue St.-Honoré, and then went on to Havre, where they joined Browning's father and sister. In October they went back, through Paris, to Florence; but after six weeks left for Rome, where, on 24 Nov., they settled in their old rooms in 43 Via Bocca di Leone. Here they saw much of Hawthorne, Massimo d'Azeglio, and Leighton. Browning, in accordance with a desire expressed by the queen, dined with the young prince of Wales at the embassy. They returned to Florence in May 1859, and to Siena, for three months, in July. It was at Florence at this time that the fierce and aged Landor presented himself to Browning with a few pence in his pocket and without a home. Browning took him to Siena and rented a cottage for him there; at the end of the year Browning secured apartments for him in Florence, where he ended his days nearly five years later.

At Siena Edward Burne-Jones and Mr. Val Prinsep joined the Brownings, and they saw much of one another the ensuing winter at Rome, whither the poets passed early in December, finding rooms at 28 Via del Tritone. Here Browning wrote 'Sludge the Medium,' in reference to Home's spiritualistic pranks, which had much affected Mrs. Browning's composition. They left Rome on 4 June 1860, and travelled by vettura to Florence, through Orvieto and Chiusi; six weeks later they were as before, to the Villa Alberti in Siena, returning to Florence in September. The steady decline of Elizabeth Browning's health was now a matter of constant anxiety; this was hastened by the news of the death of her sister, Henrietta Surtees-Cook (December 1860). From Siena the Brownings went this winter direct to Rome, to 126 Via Felice. In March 1861 Robert Browning, now nearly fifty, was 'looking remarkably well and young, in spite of all lunar lights in his hair. The women adore him everywhere far too much for decency. In my own opinion he is infinitely handsomer and more attractive than when I saw him first, sixteen years ago' (E. B. B.) At the close of May 1861, no definite alarm about Mrs. Browning being yet felt, they went back to Florence. She died at last after a few days' illness in Browning's arms, on 29 June 1861, in their apartments in Casa Guidi. Thus closed, after sixteen years of unclouded marital happiness, one of the most interesting and romantic relations between a man and woman of genius which the history of literature presents to us.

Browning was overwhelmed by a disaster which he had refused to anticipate. Miss Isa Blagden, whose friendship had long been invaluable to the Brownings in Florence, was 'perfect in all kindness' to the bereaved poet. With Browning and his little son Miss Blagden left Florence at the end of July 1861, and travelled with them to Paris, where he stayed at 151 Rue de Grenelle, Faubourg St.-Germain. Browning never returned to Florence. In Paris he parted from Miss Blagden, who went back to Italy, and he proceeded to St.-Enegat, near Dinard, where his father and sister were staying. In November 1861 he went on to London, wishing to consult with his wife's sister, Miss Arabel Barrett, as to the education of his child. She found him lodgings, as his intention was to make no lengthy stay in England ('no more housekeeping for me, even with my family'). Early in 1862, however, he became persuaded that this was a wretched arrangement, for his little son as well as for himself. Miss Arabel Barrett was living in Delamere Terrace, facing the canal, and Browning took a house, 19 Warwick Crescent, in the same line of buildings, a little further east. Here he arranged the furniture which had been around him in the Casa Guidi, and here he lived for more than five-and-twenty years.

The winter of 1861, the first, it is said, which he had ever spent in London, was inexpressibly dreary to him. He was drawn to spend it and the following years in this way from a strong sense of duty to his father, his sister, and his son. He made it, moreover, a practice to visit Miss Arabel Barrett every afternoon, and with her he first attended Bedford Chapel to listen to the eloquent sermons of Thomas Jones (1819-1882) [q. v.] He became a seatholder there, and contributed a short introduction to a collection of Jones's sermons and addresses which appeared in 1884. He lived through 1862 very quietly, in great depression of spirits, but devoted, like a mother, to the interests of his little son. In August he was persuaded to go to the Pyrenees, and spenu that month at Cambo; in September he went on to Biarritz, and here he began to meditate on 'my new poem which is about to be, the Roman murder story,' which ultimately became 'The Ring and the Book.' At the same time be made a close study of Euripides, which left a strong mark on his future work, and he saw through the press the 'Last Poems' of his wife, to which he prefixed a dedication 'to grateful Florence.' In October he returned by Paris to London.

On reappearing in London he was pestered by applications from volunteer biographers of his wife. His anguish at these impertinences disturbed his peace and even his health. On this subject his indignation remained to the last extreme, and the expressions of it were sometimes unwisely violent. 'Nothing that ought to be published shall be kept back,' however, he determined, and therefore in the course of 1863 he published Mrs. Browning's prose essays on 'The Greek Christian Poets.' His own poems appeared this year in two forms: a selection, edited by John Forster and Barry Cornwall, and a three-volume edition, relatively complete.

Up to this time the Procters (Barry Cornwall and his wife) were almost the only company he kept outside his family circle. But with the spring of 1863 a great change came over his habits. He had refused all invitations into society; but now, of evenings, after he had put his boy to bed, the solitude weighed intolerably upon him. He told the present writer, long afterwards, that it suddenly occurred to him on one such spring night in 1863 that this mode of life was morbid and unworthy, and, then and there, he determined to accept for the future every suitable invitation which came to him. Accordingly he began to dine out, and in the process of time he grew to be one of the most familiar figures of the age at every dining-table, concert-hall, and place of refined entertainment in London. This, however, was a slow process. In 1803, 1864, and 1865 Browning spent the summer at Sainte-Marie, near Pornic, 'a wild little place in Brittany,' by which he was singularly soothed and refreshed. Here he wrote most of the 'Dramatis Personse.' Early in 1864 he privately printed, as a pamphlet, 'Gold Hair : a legend of Pornic,' and later, as a volume, the important volume of 'Dramatis Personæ,' containing some of the finest and most characteristic of his work. In this year (12 Feb.) Browning's will was signed in the presence of Tennyson and F. T. Palgrave, He never modified it. Through these years his constant occupation was his 'great venture, the murder-poem,' which was now gradually taking shape as 'The Ring and the Book.' In September 1865 he was occupied in making a selection from Mrs. Browning's poems, whose fame and sale continued greatly to exceed his own, although he was now at length beginning to be widely read. In June 1866 he was telegraphed for to Paris, and arrived in time to be with his father when he died (14 June). On the 19th he returned to London, bringing his sister with him. For the remainder of his life she kept house for him. They left almost immediately for Dinard, and passed on to Le Croisic, a little town near the mouth of the Loire, which delighted Browning exceedingly. Here he took 'the most delicious and peculiar old house I ever occupied, the oldest in the town; plenty of great rooms.' It was here that he wrote the ballad of 'Hervé Riel' (September 1867) which was published four years later. During 1866 and 1867 Browning greatly enjoyed Le Croisic. In June 1868 Arabel Barrett died in Browning's arms. She had been his wife's favourite sister, and the one who resembled her most in character and temperament. Her death caused the poet long distress, and for many years he was careful never to pass her house in Delamere Terrace. In June of this year he was made an hon. M.A, of Oxford, and in October honorary fellow of Balliol College, mainly through the friendship of Jowett. At the death of J. S. Mill, in 1868, Browning was asked if he would take the lord-rectorship of St. Andrews University, but he did not feel himself justified in accepting any duties which would involve vague but considerable extra expenditure.

In 1868 Messrs. Smith, Elder, & Co. became Browning's publishers, and with Mr. George Smith the poet formed a close friendship which lasted until his death. The firm of Smith, Elder, & Co. issued in 1868 a six volume edition of Browing's works, and in November-December 1868, January-February 1869, they published, in four successive monthly instalments, 'The Ring and the Book.' Browning presented the manuscript to Mr. Smith. The history of this, the longest and most imposing of Browning's works, appears to be as follows. In June 1860 he had discovered in the Piazza San Lorenzo, Florence, a parchment-bound proces-verbal of a Roman murder case, 'the entire criminal cause of Guido Franceschini, and four cut-throats in his pay,' executed for their crimes in 1698. He bought this volume for eight-pence, read it through with intense and absorbed attention, and immediately perceived the extraordinary value of its group of parallel studies in psychology. He proposed it to Miss Ogle as the subject of a prose romance, and 'for poetic use to one of his leading contemporaries' (Mrs. Orr). It was not until after his wife's death that he determined to deal with it himself, and he first began to plan a poem on the theme at Biarritz in September 1862. He read the original documents eight times over before starting on his work, and had arrived by that time at a perfect clairvoyance, as he believed, of the motives of all the persons concerned. The reception of 'The Ring and the Book' was a triumph for the author, who now, close on the age of sixty, for the first time took his proper place in the forefront of living men of letters. The sale of his earlier works, which had been so fluctuating that at one time not a single copy of any one of them was asked for during six months, now became regular and abundant, and the night of Browning's long obscurity was over. A second edition of the entire 'Ring and the Book' was called for in 1869. In the summer of that year Browning travelled in Scotland with the Storys, ending up with a visit to Louisa, Lady Ashburton, at Loch Luichart. For the monument to Lord Dufferin's mother he composed (26 April 1870) the sonnet called 'Helen's Tower.'

The summer of this year, in spite of the Franco-German war, was spent by the Brownings with Milsand in a primitive cottage on the sea-shore at St.-Aubin, opposite Havre. The poet wrote, 'I don't think we were ever quite so thoroughly washed by the sea-air from all quarters as here.' The progress of the war troubled the Brownings' peace of mind, and, more than this, it put serious difficulties in the way of their return to England. They contrived, after some adventures, to get themselves transported by a cattle-vessel which happened to be leaving Honfleur for Southampton (September 1870). In March 1871 the 'Cornhill Magazine' published 'Hervé Riel' (which had been written in 1867 at Le Croisic); the 100l. which he was paid for the serial use of this poem he sent to the sufferers by the siege of Paris. In the course of this year Browning was writing with great activity. Through the spring months he was occupied in completing 'Balaustion's Adventure,' the dedication of which is dated 22 July 1871; it was published early in the autumn. After a very brief visit to the Milsands at St.-Aubin, Browning spent the rest of the summer of this year in Scotland, where he composed 'Prince Hohenstiel-Schwangau,' which was published early the following winter. In this year (1871) Browning was elected a life-governor of University College, London. Early in 1872 Milsand visited him in London, and Alfred Domett (Waring) came back at last from New Zealand; on the other hand, on 26 Jan. 1873 died the faithful and sympathetic Isa Blagden (cf. T. A. Teollope, What I Remember, ii. 174). In 1872 Browning published one of the most fantastic of his books, 'Fifine at the Fair,' composed in Alexandrines; this poem is reminiscent of the life at Pornie in 1863–5, and of a gipsy whom the poet saw there. Mrs. Orr records that 'it was not without misgiving that he published "Fifine." 'He spent the summer of 1872 and 1873 at St.-Aubin, meeting there in the earlier year Miss Thackeray (Mrs. Ritchie); she discussed with him the symbolism connecting the peaceful existence of the Norman peasantry with their white head-dress, and when Browning returned to London he began to compose 'Red Cotton Nightcap Country,' which was finished in January and published in June 1873, with a dedication to Miss Thackeray. In 1874, at the instance of an old friend. Miss A. Egerton-Smith, the Brownings took with her a house, Maison Robert, on the cliff" at Mers, close to Tréport, and here he wrote 'Aristophanes' Apology,' including the remarkable 'transcript' from the 'Herakles' of Euripides. At Mers his manner of life is thus described to us: 'In uninterrupted quiet, and in a room devoted to his use, Mr. Browning would work till the afternoon was advanced, and then set forth on a long walk over the cliffs, often in the face of a wind which he could lean against as if it were a wall.' 'Aristophanes' Apology' was published early in 1875. During the spring of this year he was engaged in London in writing 'The Inn Album,' which he completed and sent to press while the Brownings were at Villers-sur-Mer, in Calvados, during the summer and autumn of 1875, again in company with Miss Egerton-Smith. In the summer of 1876 the same party occupied a house in the Isle of Arran. Browning was at this time very deeply occupied in studying the Greek dramatists, and began a translation of the 'Agamemnon.' In July 1876 he published the volume known from its title-poem as 'Pacchiarotto.' This revealed in several of its numbers a condition of nervous irritability, which was reflected in the poet's daily life; he was far from well in London during these years, although a change of air to France or Scotland never failed to produce a sudden improvement in health and spirits ; and it was away from town that his poetry was mainly composed. In 1877 there appeared his translation of the 'Agamemnon' of Æschylus, and he again refused the lord-rectorship of St. Andrews University, as in 1875 he had refused that of Glasgow.

For the summer and autumn of 1877 the friends took a house at the foot of La Saleve, in Savoy, just above Geneva; it was called La Saisiaz; here Browning sat, as he said, 'aerially, like Euripides, and saw the clouds come and go.' He was not, however, in anything like his usual spirits, and he suffered a terrible shock early in September by the sudden death of Miss Egerton-Smith. The present writer recollects the extraordinary change which appeared to have passed over the poet when he reappeared in London, nor will easily forget the tumult of emotion with which he spoke of the shock of his friend's dying, almost at his feet. He put his reflections on the subject into the strange and noble poem of 'La Saisiaz,' which he finished in November 1877. He lightened the gloom of what was practically a monody on Miss Egerton-Smith by contrasting it with one of the liveliest of his French studies, 'The Two Poets of Croisic,' which he completed in January 1878. These two works, the one so solemn, the other so sunny, were published in a single volume in the spring of 1878.

In August 1878 he revisited Italy for the first time since 1861. He stayed some time at the Splügen, and here he wrote 'Ivàn Ivànovitch.' Late in September his sister and he passed on to Asolo, which, for the moment, failed to reawaken his old pleasure; and in October they went on to Venice, where they stayed in the Palazzo Brandolin-Rota. This was a comparatively short visit to Italy, but it awakened all Browning's old enthusiasm, and for the remainder of his life he went to Italy as often and for as long a time as he could contrive to. During this autumn, and while in the south, he wrote the greater part of the 'Dramatic Idyls,' published early in 1879. His fame was now universal, and he enjoyed for the first time full recognition as one of the two sovereign poets of the age. 'Tennyson and I seem now to be regarded as the two kings of Brentford,' he laughingly said in the course of this year. His sister and he returned to Venice, and to their former quarters, in the autumn of 1879 and again in that of 1880. In the latter year he published a second series of 'Dramatic Idyls,' including 'Olive,' which he was accustomed to mention as perhaps the best of all his idyllic poems 'in the Greek sense.'

In the summer of 1881 Dr. Furnivall and Miss E. H. Hickey started the 'Browning Society' for the interpretation and illustration of his writings. He received the intimation of their project with divided feelings; he could not but be gratified at the enthusiasm shown for his work after long neglect, and yet he was apprehensive of ridicule. He did not refuse to permit it, but he declined most positively to co-operate in it. He persisted, when talking of it to old friends, in treating it as a joke, and he remained to the last a little nervous about being identified with it. It involved, indeed, a position of great danger to a living writer, but, on the whole, the action of the society on the fame and general popularity of the poet was distinctly advantageous; and so much worship was agreeable to a man who had passed middle life without the due average of recognition. He became, about the same time, president of the New Shakspere Society.

The autumn of 1881 was the last which the Brownings spent at the Palazzo Brandolin-Rota. On their way to it they stopped for six weeks at Saint-Pierre-la-Chartreuse, close to the monastery, where the poet lodged three days, 'staying there through the night in order to hear the midnight mass.' This autumn, in spite of 'abominable and un-Venetian' weather, was greatly appreciated. 'I walk, even in wind and rain, for a couple of hours on Lido, and enjoy the break of sea on the strip of sand as much as Shelley did in those old days' (11 Oct. 1881). Browning had now reached his seventieth year, and, for the first time, the flow of his poetic invention seemed to flag a little. He did not write much from 1879 to 1883. In 1882 the Brownings proceeded again to Saint-Pierre-la-Chartreuse for the summer, intending to go on to Venice; but at Verona they learned that the Palazzo Brandolin-Rota had been transformed into a museum, and, while they hesitated whither they should turn, the floods of the Po cut them off from Venice. This autumn, therefore, they made Verona their headquarters; and here Browning wrote several of the poems which appeared early in 1883, under the Batavian-Latin title 'Jocoseria.'

In 1883 the Brownings spent the summer opposite Monte Rosa, at Gressoney St.-Jean, a place to which the poet became more attached than to any other Alpine station ; later on they passed to Venice, where their excellent friend, Mrs. Arthur Bronson (she died on 6 Feb. 1901), received them as her guests in the Palazzo Giustiniani Recanati. Here Browning wrote the sonnets 'Sighed Rawdon Brown' and 'Goldoni.' In these later years, his bodily endurance having steadily declined, Browning saw fewer and fewer people during his long Venetian sojourns, depending mainly outside the salon of Mrs. Bronson on 'the kindness of Sir Henry and Lady Layard, of Mr. and Mrs. Curtis of Palazzo Barbazo, and of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic Eden, for most of his social pleasure and comfort' (Mrs. Orr). In 1884 Browning was made an hon. LL.D. of the university of Edinburgh; for a third time he declined to be elected lord rector of the university of St. Andrews. There had been a suggestion in 1876 that he should stand for the professorship of poetry at Oxford; this idea was now revived, and greatly attracted him; he said that if he were elected, his first lecture would be on 'Beddoes: a forgotten Oxford Poet.' It was discovered, however, that not having taken the ordinary M. A. degree, he was not eligible. He wrote much in this year, for besides the sonnets, 'The Names' and 'The Founder of the Feast,' and an introduction to the posthumous sermons of Thomas Jones, he composed a great number of the idyls and lyrics collected in the winter of 1884 as 'Ferishtah's Fancies.' The summer of 1884 was broken up by an illness of Miss Browning, and the poet did not get to Italy at all, contenting himself with spending August and September in her villa at St.-Moritz with Mrs. Bloomfield Moore, a widow lady from Philadelphia with whom Browning was at this time on terms of close friendship.

In 1885 Browning accepted the honorary presidency of the Five Associated Societies of Edinburgh, and in April wrote the fine 'Inscription for the Gravestone of Levi Thaxter.' In the summer he went again to Gressoney St.-Jean, thence proceeding for the autumn and winter to Venice. He was now settled in the Palazzo Giustiniani Recanati, but his son, who joined him, urged the purchase of a house in Venice. Accordingly, in November 1885 Browning secured, or thought that he had secured, the Palazzo Manzoni, on the Grand Canal; but the owners, the Montecuccule, raised so many claims that he withdrew from the bargain just in time — happily, as it proved, for the foundations of the palace were not in a safe condition; but the failure of the negotiations annoyed and distressed him to a degree which betrayed his decrease of nerve power. Early in 1886 Browning succeeded Lord Houghton as the foreign correspondent to the Royal Academy, a sinecure post which he accepted at the earnest wish of Sir Frederic Leighton. Venice having ceased to attract him for a moment, in 1886 he made the poor state of health of his sister his excuse for remaining in England, his only absence from London being a somewhat lengthy autumnal residence at the Hand Hotel in Llangollen, close to the house of his friends. Sir Theodore and Lady Martin at Brintysilio. After his death a tablet was placed in the church of Llantysilio to mark the spot where the poet was seen every Sunday afternoon during those weeks of 1886. On 4 Sept. of this year his oldest friend passed away in the person of Joseph Milsand, to whose memory he dedicated the 'Parleyings' which he was now composing. This volume, the full title of which was 'Parleyings with certain People of Importance in their Day,' consisted, with a prologue and an epilogue, of seven studies in biographical psychology. In June 1887 the threat of a railway to be constructed in front of the house in which he had lived so long (a threat which was not carried out) induced him to leave 19 Warwick Crescent and take a new house in Kensington, 29 De Vere Gardens. While the change was being made he went to Mrs. Bloomfield Moore at St.-Moritz for the summer, but, instead of proceeding to Venice, returned in September to London. This winter ' he was often suffering; one terrible cold followed another. There was general evidence that he had at last grown old' (Mrs. Orr). But he was still writing; 'Rosny' belongs to December of this year, and 'Flute-Music' to January 1888. He now began to arrange for a uniform edition of his works, which he lived just long enough to see completed.

In August his sister and he left for Italy; they stayed first at Primiero, near Feltre. By this time his son (who had married in October 1887) had purchased the Palazzo Ilezzonico in Venice, with money given him for the purpose by his father, and this he was now fitting up for Browning's reception. Browning stayed first in Ca'Alvise, and had on the whole a very happy autumn and winter in Venice. He did not return to London until February 1889. 'He still maintained throughout the season his old social routine, not omitting his yearly visit, on the anniversary of Waterloo, to Lord Albemarle, its last surviving veteran' (Mrs. Orr). In the summer he paid memorable visits to Jowett at Balliol College, Oxford, and to Dr. Butler at Trinity College, Cambridge. But his strength was visibly failing, and when the time came for the customary journey to Venice, he shrank from the fatigue. However, in the middle of August he was persuaded to start for Asolo, where Mrs. Bronson was, instead of Venice. He was extremely happy at Asolo, and 'seemed possessed by a strange buoyancy — an almost feverish joy in life, which blunted all sensations of physical distress.' He tried to purchase a small house in Asolo; he meant to call it Pippa's Tower and since his death it has, with much other land in the town, become the property of his son. At the beginning of November he tore himself away from Asolo, and settled in at the Palazzo Rezzonico in Venice. He thought himself quite well, and walked each day in the Lido. But the temperature was very low, and his heart began to fail. He wrote to England (29 Nov.): 'I have caught a cold; I feel sadly asthmatic, scarcely fit to travel, but I hope for the best;' on the 30th he declared it was only his 'provoking liver,' and hoped soon to be in England. But he now sank from day to day, and at ten p.m., on 12 Dec. 1889, he died in the Palazzo Rezzonico. 'It was an unexpected blow,' his sister wrote, 'he seemed in such excellent health and exuberant spirits.' On the 14th, with solemn pomp, the body was given the ceremony of a public funeral in Venice, but on the 16th was conveyed to England, where, on 31 Dec, it was buried in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, the pall being carried by Lord Dufferin, Leighton, Sir Theodore Martin, George M. Smith (his publisher), and other illustrious friends. Browning's last volume of poems, 'Asolando,' was actually published on the day of his death; but a message with regard to the eagerness with which it had been 'subscribed' for had time to reach him on his death-bed, and he expressed his pleasure at the news. Shortly after his death memorial tablets were affixed by the city of Venice to the outer wall of the Palazzo Rezzonico, and by the Society of Arts to that of 19 Warwick Crescent. He left behind him his sister. Miss Sariana Browning, and his son, Mr. Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, who are now resident at Venice and Asolo.

Browning's rank in the literature of the nineteenth century has been the subject of endless disputation. It can be discussed here only from the point of view of the illustration of his writings by his person and character. As a contributor to thought, it is noticeable in the first place that Browning was almost alone in his generation in preaching a persistent optimism. In the latest of his published poems, in the 'Epilogue' to 'Asolando,' he sums up and states with unflinching clearness his attitude towards life. He desires to be remembered as

One who never turned his back, but marched breast forward, Never doubted clouds would break, Neverdreamed, though right were worsted, wrong would triumph. Held we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better Sleep to wake. No poet ever comprehended his own character better, or comprised the expression of it in better language. This note of militant optimism was the ruling one in Browning's character, and nothing that he wrote or said or did in his long career ever belied it. This optimism was not discouraged by the results of an impassioned curiosity as to the conditions and movements of the soul in other people. He was, as a writer, largely a psychological monologuist—that is to say, he loved to enter into the nature of persons widely different from himself, and push his study, or construction, of their experiences to the furthest limit of exploration. In these adventures he constantly met with evidences of baseness, frailty, and inconsistency; but his tolerance was apostolic, and the only thing which ever disturbed his moral equanimity was the evidences of selfishness. He could forgive anything but cruelty. His optimism accompanied his curiosity on these adventures into the souls of others, and prevented him from falling into cynicism or indignation. He kept his temper and was a benevolent observer. This characteristic in his writings was noted in his life as well. Although Browning was so sublime a metaphysical poet, nothing delighted him more than to listen to an accumulation of trifling (if exact) circumstances which helped to build up the life of a human being. Every man and woman whom he met was to Browning a poem in solution; some chemical condition might at any moment resolve any one of the multitude into a crystal. His optimism, his curiosity, and his clairvoyance occupied his thoughts in a remarkably objective way. He was of all poets the one least self-centred, and therefore in all probability the happiest. His physical conditions were in harmony with his spiritual characteristics. He was robust, active, loud in speech, cordial in manner, gracious and conciliatory in address, but subject to sudden fits of indignation which were like thunderstorms. In all these respects it seems probable that his character altered very little as the years went on. What he was as a boy, in these respects, it is believed that he continued to be as an old man. 'He missed the morbid over-refinement of the age; the processes of his mind were sometimes even a little coarse, and always delightfully direct. For real delicacy he had full appreciation, but he was brutally scornful of all exquisite morbidness. The vibration of his loud voice, his hard fist upon the table, would make very short work with cobwebs. But this external roughness, like the rind of a fruit, merely served to keep the inner sensibilities young and fresh. None of his instincts grew old. Long as he lived, he did not live long enough for one of his ideals to vanish, for one of his enthusiasms to lose its heat. The subtlest of writers, he 'was the singlest of men, and he learned in serenity what he taught in song.' The question of the 'obscurity' of his style has been mooted too often and emphasised too much by Browning's friends and enemies alike, to be passed over in silence here. But here, at the same time, it is impossible to deal with it exhaustively. Something may, however, be said in admission and in defence. We must admit that Browning is often harsh, hard, crabbed, and nodulous to the last degree; he suppressed too many of the smaller parts of speech in his desire to produce a concise and rapid impression. He twisted words out of their fit construction, he clothed extremely subtle ideas in language which sometimes made them appear not merely difficult but impossible of comprehension. Odd as it sounds to say so, these faults seem to have been the result of too facile a mode of composition. Perhaps no poet of equal importance has written so fluently and corrected so little as Browning did. On the other hand, in defence, it must be said that it is always, or nearly always, possible to penetrate Browning's obscurity, and to find excellent thought hidden in the cloud, and that time and familiarity have already made a great deal perfectly translucent which at one time seemed impenetrable even to the most respectful and intelligent reader.

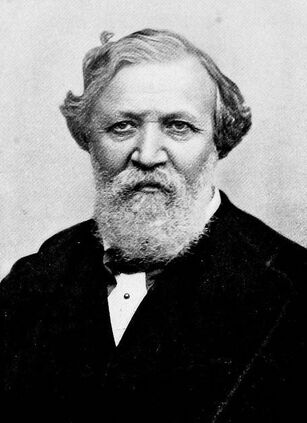

In person Browning was below the middle height, but broadly built and of great muscular strength, which he retained through life in spite of his indifference to all athletic exercises. His hair was dark brown, and in early life exceedingly full and lustrous; in middle life it faded, and in old age turned white, remaining copious to the last. The earliest known portrait of Browning is that engraved for Home's 'New Spirit of the Age' in 1844, when he was about thirty-two. In 1854 a highly finished pencil drawing of him was made in Rome by Frederic Leighton, but this appears to be lost. In 1855, or a little later, Browning was painted by Gordigiani, and in 1856 Woolner executed a bronze medallion of him. In 1859 Mr. and Mrs. Browning sat to Field Talfourd in Florence for life-sized crayon portraits, of which that of Elizabeth is now in the National Portrait Gallery, where that of Robert, long in the possession of the present writer, joined it in July 1900. Of this portrait Browning wrote long afterwards (23 Feb. 1888), 'My sister — a better authority than myself — has always liked it, as resembling its subject when his features had more resemblance to those of his mother than in after-time, when those of his father got the better — or perhaps the worse — of them.' He was again painted by Mr. G. F. Watts, R.A., about 1805, and by Mr. Rudolf Lehmann in 1859 and several later occasions. The portraits by Watts and Lehmann are in the National Portrait Gallery. In his last years Browning, with extreme good-nature, was willing to sit for his portrait to any one who asked him. He was once discovered in Venice, surrounded, like a model in a life-class, by a group of artistic ladies, each taking him off from a different point of view. Of these representations of Browning as an old man, the best are certainly those executed by his son, in particular a portrait painted in the summer and autumn of 1880.

The publications of Robert Browning, with their dates of issue, have been mentioned in the course of the narrative. The first of the collected editions, the so-called 'New Edition' of 1849, in 2 vols., was not complete even up to date. Much more comprehensive was the 'third edition' (really the second) of the 'Poetical Works of Robert Browning' issued in 1863. A 'fourth' (third) appeared in 1865. 'Selections' were published in 1863 and 1865. The earliest edition of the 'Poetical Works' which was complete in any true sense was that issued by Messrs. Smith, Elder, & Co. in 1868, in six volumes; here 'Pauline' first reappeared, and here is published for the first time the poem entitled 'Deaf and Dumb.' These volumes represent Browning's achievements down to, but not including, 'The Ring and the Book.' Further independent selections were published in 1872 and 1880; and both were reprinted in 1884. A beautiful separate edition of 'The Pied Piper of Hamelin,' made to accompany Pinwell's drawings, belongs to 1884. The edition of Browning's works, in sixteen volumes, was issued in 1888-9, and contains everything but 'Asolando.' In 1896 there appeared a complete edition, in two volumes, edited by Mr. Augustine Birrell, Q.C.,M.P., and Mr. F. G. Kenyon.===Middle years===

Browning's career began with the publication of the anonymous poem Pauline. The piece, which disappeared without notice, would embarrass him for the rest of his life. [2] The long poem Paracelsus, about the renowned doctor and alchemist, had no general popularity; nevertheless, it gained the notice of Thomas Carlyle, William Wordsworth, and other men of letters, and gave him a reputation as a poet of distinguished promise on the London scene. Browning came to befriend Charles Dickens, John Forster, Harriet Martineau and Carlyle, as well as William Charles Macready who encouraged Browning to write the play Strafford, performed in 1837 by Macready and Helen Faucit.[3] It was no great success but Browning was encouraged enough to try again, going on to write 8 plays in all, including Pippa Passes (1841) and A Soul's Tragedy (1846). A troubled production of A Blot on the 'Scutcheon (1843) was followed by the publication of the experimental and politically radical long poem Sordello (1840), which were both met with widespread derision. Tennyson commented that he only understood the first and last lines and Carlyle noted that his wife had read the poem through and could not tell whether Sordello was a man, a city or a book.[3] His reputation would not rise again for 25 years. [3]

Portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 1845, Browning met poet Elizabeth Barrett, 6 years his elder, who lived as a semi-invalid in her father's house in Wimpole Street, London. They began regularly corresponding and gradually a romance developed between them, leading to their elopement on 12 September 1846.[3]

The marriage was initially secret because Elizabeth's domineering father disapproved of marriage for any of his children. Mr. Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did for each of his children who married: "The Mrs. Browning of popular imagination was a sweet, innocent young woman who suffered endless cruelties at the hands of a tyrannical papa but who nonetheless had the good fortune to fall in love with a dashing and handsome poet named Robert Browning."[4]

At her husband's insistence, the 2nd edition of Elizabeth's Poems included her love sonnets. The book increased her popularity and high critical regard, cementing her position as an eminent Victorian poet. Upon William Wordsworth's death in 1850, she was a serious contender to become Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, the position eventually going to Tennyson.

1882 caricature from Punch Magazine reading: "The Ring and Bookmaker from Red Cotton Nightcap country"

From the time of their marriage, the Brownings lived in Italy until Elizabeth's death, first in Pisa, and then, within a year, finding an apartment in Florence at Casa Guidi (now a museum to their memory).[3] Their only child, Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, nicknamed "Penini" or "Pen", was born in 1849. [3] In these years Browning was fascinated by and learned from the art and atmosphere of Italy. He would, in later life, describe Italy as his university. Browning bought a home in Asolo, in the Veneto outside Venice.[5] As Elizabeth had inherited money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy, and their relationship together was happy. However, the literary assault on Browning's work did not let up and he was critically dismissed further, by patrician writers such as Charles Kingsley, for the desertion of England for foreign lands. [3]In Florence, Browning worked on the poems that eventually comprised his 2-volume Men and Women, for which he is now well known;[3] in 1855, however, when these were published, they made little impact. It was only after his wife's death, in 1861, when he returned to England and became part of the London literary scene — albeit while paying frequent visits in Italy — that his reputation started to take off.[3]

In 1868, after 5 years' work, he completed and published the long blank-verse poem The Ring and the Book. Based on a convoluted murder-case from 1690s Rome, the poem is composed of twelve books, essentially ten lengthy dramatic poems narrated by the various characters in the story, showing their individual perspectives on events, bookended by an introduction and conclusion by Browning himself. Long, even by Browning's own standards (over twenty thousand lines), The Ring and the Book was the poet's most ambitious project and arguably his greatest work; it has been praised as a tour de force of dramatic poetry.[6] Published separately in four volumes from November 1868 through to February 1869, the poem was a success both commercially and critically, and finally brought Browning the renown he had sought for nearly forty years.[6]

Last years[]

In the remaining years of his life Browning travelled extensively. After a series of long poems published in the early 1870's, of which Fifine at the Fair and Red Cotton Night-Cap Country were the best-received. [6] The volume Pacchiarotto, and How He Worked in Distemper included an attack against Browning's critics, especially Poet Laureate Alfred Austin. According to some reports Browning became romantically involved with Lady Ashburton, but did not re-marry. In 1878, he returned to Italy for the first time in the 17 years since Elizabeth's death, and returned there on several occasions.

In 1887, Browning produced the major work of his later years, Parleyings with Certain People of Importance In Their Day. It finally presented the poet speaking in his own voice, engaging in a series of dialogues with long-forgotten figures of literary, artistic, and philosophic history. The Victorian public was baffled by this, and Browning returned to the short, concise lyric for his last volume, Asolando (1889), published on the day of his death. [6] Browning died at his son's home Ca' Rezzonico in Venice on 12 December 1889. [6]

Writing[]

Browning as the Pied Piper. Drawing by Frederick Waddy (1848-1901), from Cartoon Portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day, 1873. Courtesy Wikisource.

Critical Introduction[]

by Margaret L. Woods

Seventy years ago the critics and the public alike were bowing Tom Moore into the House of Fame and letting down the latch upon Shelley and Keats outside. This and other shocking examples of the vanity of contemporary criticism might impose eternal silence on the critic, did they not also make it plain that his mistakes are of no earthly consequence. For such door-keepers are but mortals, and the immortals have plenty of time; they keep on knocking.

The door was obdurately shut against Browning for many years, but when it opened, it opened wide; and he is surely not of those whom another age shows out by the back way. But his exact position in England’s House of Fame that other age must determine. Mere versatility does not there count for much; since in the scales of time one thing right well done is sure to outweigh many pretty well done. But that variousness of genius which springs from a wide-sweeping imagination and sympathies that range with it counts for very much.

In his comprehension of the varied aspects of human nature, in his power of dramatically presenting them, Browning stands alone among the poets of a great poetic age. Will these things loom larger in the distance, or when Prince Posterity comes to be King, will his royal eye be caught first by uncouth forms, by obscurities and weary prolixities? We cannot tell whether our poet will be freshly crowned or coldly honoured, for he beyond all others is the intellectual representative of his own generation, and his voice is still confused and it may be magnified by its echoes in the minds of his hearers.

His own generation indeed meant more than one. He represented in some respects the generation into which he was born, but yet more a later one which he antedated. This being so, he could not expect an eager welcome from his earlier contemporaries. Phantoms of the past are recognisable, and respectable, but phantoms of the future are rarely popular.

Yet it was fortunate that he stood just where he did in time, rather than nearer to those who were coming to meet him and call him Master. For he was born while the divine breath of Poetry, that comes we know not whence and goes we know not whither, was streaming over England. He grew up through years when she stood elate, with victory behind her, and looking forward with all manner of sanguine beliefs in the future. So he brought into a later age not only the fuller poetic inspiration, the sincere Romance of the earlier, but its sanguine confident temperament.

This temperament alone would not have recommended him to a generation which had been promised Canaan and landed in a quagmire, had it not been combined with others which made him one of themselves. But this being so, his cheerful courage, his belief in God and the ultimate triumph of good were as a tower of strength to his weaker brethren. It was not only as a poet, but as a prophet or philosopher, that he won his disciples.

He himself once said that “the right order of things” is “Philosophy first, and Poetry, which is its highest outcome, afterwards.” Yet this union of Philosophy and Poetry is dangerous, especially if Philosophy be allowed to take precedence. For Philosophy is commonly more perishable than Poetry, or at any rate it is apt sooner to require resetting to rid it of an antiquated air. Whatever is worth having in the philosophy of a Rousseau soon passes into the common stock. Emile is dead, but Rousseau lives by his pictures of beautiful Nature and singular human nature.

Browning’s philosophy is mainly religious. It has been said of him with truth: “His processes of thought are often scientific in their precision of analysis; the sudden conclusion which he imposes upon them is transcendental and inept.” This was not so much due to a defect in his own mind as to the circumstances of the world of thought about him. An interest in theological questions had been quickened and spread by more than one religious revival, and then scientific and historical criticism began to make its voice heard. Intelligent religious people could not close their ears to it, but they were as yet unprepared either to accept or to effectually combat its conclusions. Hence there arose in very many minds a confusion between two opposing strains of thought, similar to that which has been remarked in Browning’s poetry, and something like a religious system in which what was called Doubt and Faith had each its allotted part. Here was plainly a transition state of thought, and it is one from which men’s minds have already moved away in opposite directions; but it has left deep traces on the literature of the middle Victorian period.

Browning’s philosophy does not fundamentally differ from that of other poets and writers of the time. It was by his superior powers of analysis, by the swiftness and ingenuity of his mind, that he was in advance of them and retained his influence over a generation that had ceased to look to them for guidance. Besides, his philosophy does not all bear the stamp of the temporary. He has some less transient religious thoughts, and many varied and fertile views of human life, breathing energy, courage, benignant wisdom: and those who like can make a system of them.

But it is not by Philosophy, it is by Imagination and Form that a poet lives. In a century that has been wonderfully enriched with song, a time when we have all grown epicures in our taste for exquisite verse, too much has been said about Browning’s want of form. It would be an absurdity to call a man a poet who had no sense of poetic form, who could not sing. Browning was a poet but not always a singer; song was not to him the inevitable language, the supreme instinct. When he strains his metre by attempting to pack more meaning into a line than it will bear with grace, when he juggles with far-fetched and hideous rhymes, he really ceases to be a poet and puts his laurels in jeopardy. But oftener his form, more especially his blank verse form, is justified by the fact that he is essentially a dramatic poet; his verse must fit the character and the mood in which he speaks.

The Elizabethans, who were no fumblers in the matter of metre, had their reasons for choosing a form for dramatic verse which should be not severe, but loose and flexible; a form which might alternately approach the classical iambus, a lyric measure and plain prose, yet remain more forcible than prose by the retention of a certain beat. It resembles not a mask and cothurn, but a fine and flowing garment, following the movements of the actor’s limbs. Great is the liberty of English unrhymed verse, and nobly it has been used; it has given us the most various treasures, from the ordered magnificence of Paradise Lost to the lyric cry of Romeo at Juliet’s grave.

Browning has often misused his liberty, but by no means so often as his hasty critics suppose. Try to think of Caliban upon Setebos, and even Dominus Hyacinthus, in prose, and you see at once by the loss involved that they are really poems; that is, that the verse form, and their own special form, is an essential part of their excellence. His unrhymed verse is seldom or never rich and stately, it is sometimes harsh and huddled; but it is constantly vigorous and appropriate, it can flow with a clear idyllic grace, as in Cleon and Andrea del Sarto, or spring up in simple lyric beauty, as in "One Word more" and the dedication to The Ring and the Book.

He had that great gift of singing straight from the heart which some great poets have lacked. Such songs have always an incommunicable charm, a piercing sweetness of their own. A strong emotion, whether personal or dramatic, has a magical effect in smoothing what is rugged and clearing what is turbid in Browning’s style.

For the rest, he wrote Pippa Passes, the gallant marching Cavalier Songs, the galloping ballad of "How they brought the Good News," the serene harmonies of "Love among the Ruins." These, and many other outbursts of beautiful song, make it doubly ridiculous to speak of him as a poet who could not sing. Yet is it true that he frequently sacrificed sound to sense. This the plain person thinks right, but the poet knows or should know it to be wrong. And it did not even save him from obscurity.

Such are his deficiencies — the more noticeable because the whole tendency of the century has been and is toward the perfecting of lyric and narrative forms of verse. In dramatic poetry this age of poets has been strangely poor. Let Shelley’s lurid drama of The Cenci be set aside in the high place that it deserves: after that the first seventy years of this century produced nothing of importance as dramatic poetry except Browning’s work. For what makes work dramatic? Not special fitness for the stage, but the author’s impersonality and power of characterisation; the clash of human passions and interests on each other, the event or even the accident, that as in a lightning-flash reveals the dim hearts of men. In his dramatic power Browning stands alone among the poets of the nineteenth century.