No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| occupation = Short story writer, novelist, poet, journalist |

| occupation = Short story writer, novelist, poet, journalist |

||

| genre = Short story, novel, children's literature, poetry, travel literature, science fiction |

| genre = Short story, novel, children's literature, poetry, travel literature, science fiction |

||

| − | | notableworks = '' |

+ | | notableworks = ''The Jungle Book'', ''Just So Stories'', ''Kim'', "If--," "Gunga Din" |

| influences = |

| influences = |

||

| − | | influenced = Robert A. Heinlein, |

+ | | influenced = Robert A. Heinlein, Jorge Luis Borges, Roald Dahl |

| awards = {{awd|[[Nobel Prize in Literature]]|1907}}<!-- do not add image icons such as nobel peace, see [[:Template:Infobox writer]] --> |

| awards = {{awd|[[Nobel Prize in Literature]]|1907}}<!-- do not add image icons such as nobel peace, see [[:Template:Infobox writer]] --> |

||

| nationality = {{Flagicon|United Kingdom}} British |

| nationality = {{Flagicon|United Kingdom}} British |

||

Revision as of 21:41, 10 August 2020

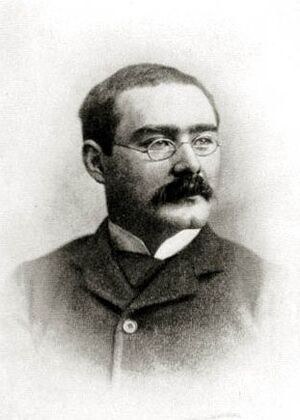

Rudyard Kipling. From Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer, Henry Holt & Co., 1915. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Joseph Rudyard Kipling (30 December 1865 - 18 January 1936) was an English poet, short story writer, and novelist chiefly remembered for his celebration of British imperialism, tales and poems of British soldiers in India, and his stories for children. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907.[1]

Kipling is best known for his works of fiction, including The Jungle Book (1894) (a collection of stories which includes "Rikki-Tikki-Tavi"), Kim (1901) (a tale of adventure), many short stories, including "The Man Who Would Be King" (1888); and his poems, including "Mandalay" (1890), "Gunga Din" (1890), "The White Man's Burden" (1899) and "If--" (1910). He is regarded as a major "innovator in the art of the short story";[2] his children's books are enduring classics of children's literature; and his best works are said to exhibit "a versatile and luminous narrative gift".[3][4]

Life

Youth

Rudyard Kipling was born on 30 December 1865 in Bombay (now Mumbai), in British India to Alice Kipling (nee MacDonald)]] and (John) Lockwood Kipling.[5] Alice (one of four remarkable Victorian sisters)[6] was a vivacious woman[7] about whom a future Viceroy of India would say, "Dullness and Mrs. Kipling cannot exist in the same room."[2] Lockwood Kipling, a sculptor and pottery designer, was the principal and professor of architectural sculpture at the newly-founded Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art and Industry in Bombay.[7]

The couple, who had moved to India in the same year Rudyard was born, had met in courtship two years previously at Rudyard Lake in Rudyard, Staffordshire, England, and had been so taken by its beauty that they now named their firstborn after it. Kipling's maternal aunt, Georgiana, was married to painter Edward Burne-Jones and his aunt Agnes was married to painter Edward Poynter. His most famous relative was his first cousin, Stanley Baldwin, who was Conservative Prime Minister of the UK 3 times in the 1920s and 1930s.[8] Kipling's birth home still stands on the campus of the J.J. School of Art in Mumbai, and for many years was used as the Dean's residence. Mumbai historian Foy Nissen points out, however, that although the cottage bears a plaque stating that this is the site where Kipling was born, the original cottage was pulled down decades ago and a new one built in its place. The wooden bungalow has been empty and locked up for years.[9]

Kipling's India: map of British India

Of Bombay, Kipling was to write:[10]

Mother of Cities to me,

For I was born in her gate,

Between the palms and the sea,

Where the world-end steamers wait.

According to Bernice M. Murphy, "Kipling's parents considered themselves 'Anglo-Indians' (a term used in the 19th century for people of British origin living in India) and so too would their son, though he spent the bulk of his life elsewhere. Complex issues of identity and national allegiance would become prominent features in his fiction."[11] Kipling himself was to write about these conflicts: "In the afternoon heats before we took our sleep, she (the Portuguese ayah, or nanny) or Meeta (the Hindu bearer, or male attendant) would tell us stories and Indian nursery songs all unforgotten, and we were sent into the dining-room after we had been dressed, with the caution 'Speak English now to Papa and Mamma.' So one spoke 'English', haltingly translated out of the vernacular idiom that one thought and dreamed in".[12]

Kipling's days of "strong light and darkness" in Bombay were to end when he was 5 years old.[12] As was the custom in British India, he and his 3-year-old sister, Alice (or "Trix"), were taken to England - in their case to Southsea (Portsmouth), to be cared for by a couple that took in children of British nationals living in India. The two children would live with the couple, Captain and Mrs. Holloway, at their house, Lorne Lodge, for the next 6 years. In his autobiography, published some 65 years later, Kipling would recall this time with horror, and wonder ironically if the combination of cruelty and neglect he experienced there at the hands of Mrs. Holloway might not have hastened the onset of his literary life: "If you cross-examine a child of seven or eight on his day's doings (specially when he wants to go to sleep) he will contradict himself very satisfactorily. If each contradiction be set down as a lie and retailed at breakfast, life is not easy. I have known a certain amount of bullying, but this was calculated torture - religious as well as scientific. Yet it made me give attention to the lies I soon found it necessary to tell: and this, I presume, is the foundation of literary effort".[12]

Kipling's sister Trix fared better at Lorne Lodge as Mrs. Holloway apparently hoped that Trix would eventually marry the Holloway son.[13] The two children, however, did have relatives in England they could visit. They spent a month each Christmas with their maternal aunt Georgiana ("Georgy"), and her husband at their house, "The Grange" in Fulham, London, which Kipling was to call "a paradise which I verily believe saved me."[12] In the spring of 1877, Alice returned from India and removed the children from Lorne Lodge. Kipling remembers, "Often and often afterwards, the beloved Aunt would ask me why I had never told any one how I was being treated. Children tell little more than animals, for what comes to them they accept as eternally established. Also, badly-treated children have a clear notion of what they are likely to get if they betray the secrets of a prison-house before they are clear of it".[12]

The Westward Ho! Ladies Golf Club at Bideford

In January 1878 Kipling was admitted to the United Services College, at Westward Ho!, Devon, a school founded a few years earlier to prepare boys for the armed forces. The school proved rough going for him at first, but later led to firm friendships, and provided the setting for his schoolboy stories Stalky & Co. published many years later.[13] During his time there, Kipling also met and fell in love with Florence Garrard, a fellow boarder with Trix at Southsea (to which Trix had returned). Florence was to become the model for Maisie in Kipling's first novel, The Light that Failed (1891).[13]

Kipling's England: Map of England Showing Kipling's Homes

Towards the end of his stay at the school, it was decided that he lacked the academic ability to get into Oxford University on a scholarship[13] and his parents lacked the wherewithal to finance him.[7] Consequently, Lockwood obtained a job for his son in Lahore, Punjab]] (now in Pakistan), where Lockwood was now Principal of the Mayo College of Art and Curator of the Lahore Museum. Kipling was to be assistant editor of a small local newspaper, the Civil & Military Gazette.

He sailed for India on 20 September 1882 and arrived in Bombay on 18 October 1882. He described this moment years later: "So, at sixteen years and nine months, but looking four or five years older, and adorned with real whiskers which the scandalised Mother abolished within one hour of beholding, I found myself at Bombay where I was born, moving among sights and smells that made me deliver in the vernacular sentences whose meaning I knew not. Other Indian-born boys have told me how the same thing happened to them."[12] This arrival changed Kipling, as he explains, "There were yet three or four days' rail to Lahore, where my people lived. After these, my English years fell away, nor ever, I think, came back in full strength".[12]

Early travels

The Civil and Military Gazette in Lahore, the newspaper which Kipling was to call "mistress and most true love,"[12] appeared 6 days a week throughout the year except for a 1-day break each for Christmas and Easter. Kipling was worked hard by the editor, Stephen Wheeler, but his need to write was unstoppable. In 1886, he published a collection of verse, Departmental Ditties. That year also brought a change of editors at the newspaper. Kay Robinson, the new editor, allowed more creative freedom and Kipling was asked to contribute short stories to the newspaper.[3]

Lahore Railway Station

During the summer of 1883, Kipling visited Simla (now Shimla), well-known hill station and summer capital of British India. By then it was established practice for the Viceroy of India and the government to move to Simla for 6 months, and the town became a "centre of power as well as pleasure."[3] Kipling's family became yearly visitors to Simla and Lockwood Kipling was asked to serve in the Christ Church there. He returned to Simla for his annual leave each year from 1885 to 1888, and the town figured prominently in many of the stories Kipling was writing for the Gazette.[3] Kipling describes this time: "My month's leave at Simla, or whatever Hill Station my people went to, was pure joy - every golden hour counted. It began in heat and discomfort, by rail and road. It ended in the cool evening, with a wood fire in one's bedroom, and next morn—thirty more of them ahead! - the early cup of tea, the Mother who brought it in, and the long talks of us all together again. One had leisure to work, too, at whatever play-work was in one's head, and that was usually full."[12] Back in Lahore, some thirty-nine stories appeared in the Gazette between November 1886 and June 1887. Most of these stories were included in Plain Tales from the Hills, which was published in Calcutta in January 1888, a month after his 22nd birthday. Kipling's time in Lahore, however, had come to an end. In November 1887, he had been transferred to the Gazette's much larger sister newspaper, The Pioneer, in Allahabad in the United Provinces.

Kipling in his study, 1895

Bundi, Rajputana, where Kipling was inspired to write Kim.

His writing continued at a frenetic pace and during the following year, he published 6 collections of short stories: Soldiers Three, The Story of the Gadsbys, In Black and White, Under the Deodars, The Phantom Rickshaw, and Wee Willie Winkie, containing a total of 41 stories, some quite long. In addition, as The Pioneer's special correspondent in western region of Rajputana, he wrote many sketches that were later collected in Letters of Marque and published in From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, Letters of Travel.[3]

In early 1889, The Pioneer relieved Kipling of his charge over a dispute. For his part, Kipling had been increasingly thinking about the future. He sold the rights to his six volumes of stories for £200 and a small royalty, and the Plain Tales for £50; in addition, from The Pioneer, he received six-months' salary in lieu of notice.[12] He decided to use this money to make his way to London, the centre of the literary universe in the British Empire. On 9 March 1889, Kipling left India, travelling first to San Francisco via Rangoon, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan. He then travelled through the United States writing articles for The Pioneer that too were collected in From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, Letters of Travel. Starting his American travels in San Francisco, Kipling journeyed north to Portland, Oregon; on to Seattle, Washington; up into Canada, to Victoria and Vancouver, British Columbia; back into the U.S. to Yellowstone National Park; down to Salt Lake City; then east to Omaha, Nebraska and on to Chicago, Illinois; then to Beaver, Pennsylvania, on the Ohio River to visit the Hill family; from there he went to Chautauqua with Professor Hill, and later to Niagara Falls, Toronto, Washington, D.C., New York and Boston.[14] In the course of this journey he met Mark Twain in Elmira, New York, and felt awed in his presence. Kipling then crossed the Atlantic, and reached Liverpool in October 1889. Soon thereafter, he made his debut in the London literary world to great acclaim.[2]

Career as a writer

London

The building on Villiers Street off the Strand in London where Kipling rented rooms from 1889 to 1891

In London, Kipling had several stories accepted by various magazine editors. He also found a place to live for the next two years:

Meantime, I had found me quarters in Villiers Street, Strand, which forty-six years ago was primitive and passionate in its habits and population. My rooms were small, not over-clean or well-kept, but from my desk I could look out of my window through the fanlight of Gatti's Music-Hall entrance, across the street, almost on to its stage. The Charing Cross trains rumbled through my dreams on one side, the boom of the Strand on the other, while, before my windows, Father Thames under the Shot Tower walked up and down with his traffic.[15]

In the next 2 years, and in short order, he published a novel, The Light that Failed; had a nervous breakdown; and met an American writer and publishing agent, Wolcott Balestier, with whom he collaborated on a novel, The Naulahka (a title he uncharacteristically misspelt; see below).[7] In 1891, on the advice of his doctors, Kipling embarked on another sea voyage visiting South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and once again India. However, he cut short his plans for spending Christmas with his family in India when he heard of Wolcott Balestier's sudden death from typhoid fever, and immediately decided to return to London. Before his return, he had used the telegram to propose to and be accepted by Wolcott's sister Caroline (Carrie) Balestier, whom he had met a year earlier, and with whom he had apparently been having an intermittent romance.[7] Meanwhile, late in 1891, his collection of short stories of the British in India, Life's Handicap, was also published in London.(Citation needed)

Kipling photographed by Bourne & Shepherd, ca. 1892

On 18 January 1892, Carrie Balestier (aged 29) and Rudyard Kipling (aged 26) were married in London, in the "thick of an influenza epidemic, when the undertakers had run out of black horses and the dead had to be content with brown ones."[12] The wedding was held at All Souls Church, Langham Place. Henry James gave the bride away.(Citation needed)

United States

The couple settled upon a honeymoon that would take them first to the United States (including a stop at the Balestier family estate near Brattleboro, Vermont) and then on to Japan.[7] However, when they arrived in Yokohama, Japan, they discovered that their bank, The New Oriental Banking Corporation, had failed. Taking their loss in stride, they returned to the U.S., back to Vermont - Carrie by this time was pregnant with their first child - and rented a small cottage on a farm near Brattleboro for ten dollars a month. According to Kipling, "We furnished it with a simplicity that fore-ran the hire-purchase system. We bought, second or third hand, a huge, hot-air stove which we installed in the cellar. We cut generous holes in our thin floors for its eight inch tin pipes (why we were not burned in our beds each week of the winter I never can understand) and we were extraordinarily and self-centredly content."[12]

Naulakha, in Dummerston, Vermont

In this cottage, Bliss Cottage, their first child, Josephine, was born "in three foot of snow on the night of 29 December 1892. Her Mother's birthday being the 31st and mine the 30th of the same month, we congratulated her on her sense of the fitness of things ..."[12]

Cover of The Jungle Book first edition

It was also in this cottage that the beginnings of the Jungle Books came to Kipling: "workroom in the Bliss Cottage was seven feet by eight, and from December to April the snow lay level with its window-sill. It chanced that I had written a tale about Indian Forestry work which included a boy who had been brought up by wolves. In the stillness, and suspense, of the winter of '92 some memory of the Masonic Lions of my childhood's magazine, and a phrase in Haggard's Nada the Lily, combined with the echo of this tale. After blocking out the main idea in my head, the pen took charge, and I watched it begin to write stories about Mowgli and animals, which later grew into the two Jungle Books ".[12] With Josephine's arrival, Bliss Cottage was felt to be congested, so eventually the couple bought land - Template:Convert/LoffAoffDbSoffNa on a rocky hillside overlooking the Connecticut River - from Carrie's brother Beatty Balestier, and built their own house.

Kipling named the house "Naulakha" in honour of Wolcott and of their collaboration, and this time the name was spelled correctly.[7] From his early years in Lahore (1882-1887), Kipling had become enthused by the Mughal architecture[16] especially the Naulakha pavilion situated in Lahore Fort, which eventually became an inspiration for the title of his novel as well as the house.[17] The house still stands on Kipling Road, three miles (5 km) north of Brattleboro in Dummerston: a big, secluded, dark-green house, with shingled roof and sides, which Kipling called his "ship", and which brought him "sunshine and a mind at ease."[7] His seclusion in Vermont, combined with his healthy "sane clean life", made Kipling both inventive and prolific.

Rudyard Kipling's America 1892-1896, 1899

In the short span of 4 years, he produced, in addition to the Jungle Books, the short story collection The Day's Work, the novel Captains Courageous, and a profusion of poetry, including the volume The Seven Seas. The collection of Barrack-Room Ballads, originally published individually for the most part in 1890, which contains his poems "Mandalay" and "Gunga Din" was issued in March 1892. He especially enjoyed writing the Jungle Books - both masterpieces of imaginative writing - and enjoyed, too, corresponding with the many children who wrote to him about them.[7]

The writing life in Naulakha was occasionally interrupted by visitors, including his father, who visited soon after his retirement in 1893,[7] and British author Arthur Conan Doyle, who brought his golf-clubs, stayed for 2 days, and gave Kipling an extended golf lesson.[18][19] Kipling seemed to take to golf, occasionally practising with the local Congregational minister, and even playing with red painted balls when the ground was covered in snow.[5][19] However, the latter game was "not altogether a success because there were no limits to a drive; the ball might skid two miles (3 km) down the long slope to Connecticut river."[5]

From all accounts, Kipling loved the outdoors,[7] not least of whose marvels in Vermont was the turning of the leaves each fall. He described this moment in a letter: "A little maple began it, flaming blood-red of a sudden where he stood against the dark green of a pine-belt. Next morning there was an answering signal from the swamp where the sumacs grow. Three days later, the hill-sides as fast as the eye could range were afire, and the roads paved, with crimson and gold. Then a wet wind blew, and ruined all the uniforms of that gorgeous army; and the oaks, who had held themselves in reserve, buckled on their dull and bronzed cuirasses and stood it out stiffly to the last blown leaf, till nothing remained but pencil-shadings of bare boughs, and one could see into the most private heart of the woods."[20]

In February 1896, the couple's 2nd daughter, Elsie, was born. By this time, according to several biographers, their marital relationship was no longer light-hearted and spontaneous.[21] Although they would always remain loyal to each other, they seemed now to have fallen into set roles.[7] In a letter to a friend who had become engaged around this time, the 30 year old Kipling offered this sombre counsel: marriage principally taught "the tougher virtues - such as humility, restraint, order, and forethought."[22]

Josephine, 1895

The Kiplings loved life in Vermont and might have lived out their lives there, were it not for two incidents - one of global politics, the other of family discord - that hastily ended their time there. By the early 1890s, the United Kingdom and Venezuela had long been locking horns over a border dispute involving British Guiana. Several times, the U.S. had offered to arbitrate, but in 1895 the new American Secretary of State Richard Olney upped the ante by arguing for the American "right" to arbitrate on grounds of sovereignty on the continent (see the Olney interpretation as an extension of the Monroe Doctrine).[7] This raised hackles in the UK and before long the incident had snowballed into a major Anglo-American crisis, with talk of war on both sides.

Although the crisis led to greater U.S.-British cooperation, at the time Kipling was bewildered by what he felt was persistent anti-British sentiment in the U.S., especially in the press.[7] He wrote in a letter that it felt like being "aimed at with a decanter across a friendly dinner table."[22] By January 1896, he had decided, according to his official biographer,[5] to end his family's "good wholesome life" in the U.S. and seek their fortunes elsewhere.

A family dispute became the final straw. For some time, the relations between Carrie and her brother Beatty Balestier had been strained on account of his drinking and insolvency. In May 1896, an inebriated Beatty ran into Kipling on the street and threatened him with physical harm.[7] The incident led to Beatty's eventual arrest, but in the subsequent hearing, and the resulting publicity, Kipling's privacy was completely destroyed, and left him feeling both miserable and exhausted. In July 1896, a week before the hearing was to resume, the Kiplings hurriedly packed their belongings and left Naulakha, Vermont, and the U.S. for good.[5]

Devon

Back in England, in September 1896, the Kiplings found themselves in Torquay on the coast of Devon, in a hillside home overlooking the sea. Although Kipling did not much care for his new house, whose design, he claimed, left its occupants feeling dispirited and gloomy, he managed to remain productive and socially active.[7] Kipling was now a famous man, and in the previous two or three years, had increasingly been making political pronouncements in his writings. His son, John, was born in August 1897. He had also begun work on two poems, "Recessional" (1897) and "The White Man's Burden" (1899) which were to create controversy when published. Regarded by some as anthems for enlightened and duty-bound empire-building (that captured the mood of the Victorian age), the poems equally were regarded by others as propaganda for brazenfaced imperialism and its attendant racial attitudes; still others saw irony in the poems and warnings of the perils of empire.[7]

Take up the White Man's burden -

Send forth the best ye breed -

Go, bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait, in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild -

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

The White Man's Burden[23]

There was also foreboding in the poems, a sense that all could yet come to naught.[24]

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet.

Lest we forget - lest we forget!

-Recessional[25]

A prolific writer during his time in Torquay, he also wrote Stalky & Co., a collection of school stories (born of his experience at the United Services College in Westward Ho!) whose juvenile protagonists displayed a know-it-all, cynical outlook on patriotism and authority. According to his family, Kipling enjoyed reading aloud stories from Stalky & Co. to them, and often went into spasms of laughter over his own jokes.[7]

South Africa

Kipling in South Africa

In early 1898 Kipling and his family travelled to South Africa for their winter holiday, thus beginning an annual tradition which (excepting the following year) was to last until 1908. With his newly minted reputation as the poet of the Empire, Kipling was warmly received by some of the most influential politicians of the Cape Colony, including Cecil Rhodes, Sir Alfred Milner, and Leander Starr Jameson. In turn, Kipling cultivated their friendship and came to greatly admire all three men and their politics. The period 1898-1910 was a crucial one in the history of South Africa and included the Second Boer War (1899-1902), the ensuing peace treaty, and the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. Back in England, Kipling wrote poetry in support of the British cause in the Boer War and on his next visit to South Africa in early 1900, he helped start a newspaper, The Friend, for Lord Roberts for the British troops in Bloemfontein, the newly captured capital of the Orange Free State. Although his journalistic stint was to last only two weeks, it was the first time Kipling would work on a newspaper staff since he left The Pioneer in Allahabad more than ten years earlier[7] and at The Friend he made lifelong friendships with Perceval Landon, H. A. Gwynne and others.[26] He also wrote articles published more widely expressing his views on the conflict.[27] Kipling penned an inscription for the Honoured Dead Memorial (Siege memorial) in Kimberley.

Sussex

In 1902, Rudyard Kipling bought Batemans, a house built in 1634 and located in rural Burwash, East Sussex, England. The house, along with the surrounding buildings, the mill and Template:Convert/LoffAoffDbSoffNa was purchased for £9,300. It had no bathroom, no running water upstairs and no electricity but Kipling loved it. "Behold us, lawful owners of a grey stone lichened house - A.D. 1634 over the door - beamed, panelled, with old oak staircase, and all untouched and unfaked. It is a good and peaceable place," he wrote in November 1902. "We have loved it ever since our first sight of it." [28][29]

Other writing

"He sat in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam-Zammeh, on her old platform, opposite the old Ajaibgher, the Wonder House, as the natives called the Lahore Museum".—Kim

Kipling began collecting material for another of his children's classics, Just So Stories for Little Children. That work was published in 1902, and another of his enduring works, Kim, first saw the light of day the previous year.

On a visit to the United States in 1899, Kipling and Josephine developed pneumonia, from which she eventually died. During the First World War, he wrote a booklet The Fringes of the Fleet[30] containing essays and poems on various nautical subjects of the war. Some of the poems were set to music by English composer Sir Edward Elgar.

Kipling wrote 2 science fiction short stories, With the Night Mail (1905) and As Easy As A. B. C (1912), both set in the 21st century in Kipling's Aerial Board of Control universe. These read like modern hard science fiction.[31]

In 1934 he published a short story in Strand Magazine, "Proofs of Holy Writ", which postulated that William Shakespeare had helped to polish the prose of the King James Bible.[32] In the non-fiction realm he also became involved in the debate over the British response to the rise in German naval power, publishing a series of articles in 1898 which were collected as A Fleet in Being.

Peak of his career

The opening decade of the 20th century saw Kipling at the height of his popularity. In 1907 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. The prize citation said: "In consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author." Nobel prizes had been established in 1901 and Kipling was the first English language recipient. At the award ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December 1907, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy praised both Kipling and 3 centuries of English literature:[33]

The Swedish Academy, in awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature this year to Rudyard Kipling, desires to pay a tribute of homage to the literature of England, so rich in manifold glories, and to the greatest genius in the realm of narrative that that country has produced in our times.

"Book-ending" this achievement was the publication of 2 connected poetry and story collections: Puck of Pook's Hill and Rewards and Fairies in 1906 and 1910 respectively. The latter contained the poem "If--".[34] This exhortation to self-control and stoicism is arguably Kipling's most famous poem. In a 1995 BBC opinion poll, it was voted the UK's favourite poem.

Kipling sympathised with the anti-Home Rule stance of Irish Unionists. He was friends with Edward Carson, the Dublin-born leader of Ulster Unionism, who raised the Ulster Volunteers to oppose "Home Rule" in Ireland. Kipling wrote the poem "Ulster" in 1912 reflecting this. Kipling was a staunch opponent of Bolshevism, a position he shared with his friend Henry Rider Haggard. The 2 had bonded upon Kipling's arrival in London in 1889 largely on the strength of their shared opinions, and they remained lifelong friends.

Many have wondered why he was never made Poet Laureate. Some claim that he was offered the post during the interregnum of 1892-96 and turned it down.

At the beginning of World War I, like many other writers, Kipling wrote pamphlets which enthusiastically supported the UK's war aims.

Freemasonry

According to the English magazine Masonic Illustrated, Kipling became a Freemason in about 1885, some 6 months prior to the usual minimum age of 21.[35] He was initiated into Hope and Perseverance Lodge No. 782 in Lahore. He later wrote to The Times, "I was Secretary for some years of the Lodge . . . , which included Brethren of at least four creeds. I was entered [as an Apprentice] by a member from Brahmo Somaj, a Hindu, passed [to the degree of Fellow Craft] by a Mohammedan, and raised [to the degree of Master Mason] by an Englishman. Our Tyler was an Indian Jew." Kipling so loved his masonic experience that he memorialised its ideals in his famous poem, "The Mother Lodge".[36]

Effects of the First World War

Kipling's only son, John, died in 1915 at the Battle of Loos. John's death inspired Kipling's poem, "My Boy Jack", and the incident became the basis for the play My Boy Jack and its subsequent television adaptation, along with the documentary Rudyard Kipling: A Remembrance Tale. Until 1992, John's burial place was unknown, but then the Commonwealth War Graves Commission reported that it had located his final resting place, but there was controversy over whether this identification was correct and if the officer buried there was John. However, in 2002 the Commonwealth War Graves Commission confirmed that the grave is in fact that of Lieutenant John Kipling.[37] After his son's death, he also wrote, "If any question why we died/ Tell them, because our fathers lied." It is speculated that these words may reveal Kipling's feelings of guilt at his role in getting John a commission in the Irish Guards, despite his initially having been rejected by the army because of his poor eyesight, and his having exerted great influence to have his son accepted for officer training at the age of only 17.[38]

Kipling, aged 60, on the cover of Time magazine, 27 September 1926. Courtesy Wikipedia.

Partly in response to this tragedy, Kipling joined Sir Fabian Ware's Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission), the group responsible for the garden-like British war graves that can be found to this day dotted along the former Western Front and all the other locations around the world where troops of the British Empire lie buried. Kipling's most significant contribution to the project was his selection of the biblical phrase "Their Name Liveth For Evermore" (Sirach 44.14, KJV) found on the Stones of Remembrance in larger war graves and his suggestion of the phrase "Known unto God" for the gravestones of unidentified servicemen. He chose the inscription "The Glorious Dead" on the Cenotaph, Whitehall, London. He also wrote a two-volume history of the Irish Guards, his son's regiment, that was published in 1923 and is considered to be one of the finest examples of regimental history.[39] Kipling's moving short story, "The Gardener", depicts visits to the war cemeteries, and the poem "The King's Pilgrimage" (1922) depicts a journey made by King George V, touring the cemeteries and memorials under construction by the Imperial War Graves Commission. With the increasing popularity of the automobile, Kipling became a motoring correspondent for the British press, and wrote enthusiastically of his trips around England and abroad, even though he was usually driven by a chauffeur.

Kipling became friends with a French soldier whose life had been saved in the First World War when his copy of Kim, which he had in his left breast pocket, stopped a bullet. The soldier presented Kipling with the book (with bullet still embedded) and his Croix de Guerre as a token of gratitude. They continued to correspond, and when the soldier, Maurice Hammoneau, had a son, Kipling insisted on returning the book and medal.[40]

In 1922, Kipling, who had made reference to the work of engineers in some of his poems and writings, was asked by a University of Toronto civil engineering professor for his assistance in developing a dignified obligation and ceremony for graduating engineering students. Kipling was very enthusiastic in his response and shortly produced both, formally entitled "The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer". Today, engineering graduates all across Canada are presented with an iron ring at the ceremony as a reminder of their obligation to society.[41] The same year Kipling became Lord Rector of St Andrews University in Scotland, a three-year position.

Death

Kipling kept writing until the early 1930s, but at a slower pace and with much less success than before. He died of a perforated duodenal ulcer on 18 January 1936,[42] 2 days before George V, at the age of 70. (His death had in fact previously been incorrectly announced in a magazine, to which he wrote, "I've just read that I am dead. Don't forget to delete me from your list of subscribers.")

Writing

Various writers, most notably Edmund Candler, were very strongly influenced by the works of Kipling. T.S. Eliot, a very different poet, edited A Choice of Kipling's Verse (1943), although in doing so he commented that "we have to defend Kipling against the charge of excessive lucidity," against "the charge of being a 'journalist' appealing only to the commonest collective emotion," and against "the charge of writing jingles."[43]

Kipling's stories for adults also remain in print and have garnered high praise from writers as different as Poul Anderson, Jorge Luis Borges, and George Orwell. His children's stories remain popular; and Kipling's work continues to be highly popular today.

Recognition

Rudyard Kipling was one of the most popular writers in England, in both prose and verse, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[2] Henry James said of him: "Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius (as distinct from fine intelligence) that I have ever known."[2]

In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, making him the first English language writer to receive the prize, and to date he remains its youngest recipient.[44]

Among other honours, he was sounded out for the post of Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, and on several occasions for a knighthood, all of which he declined.[45]

On 23 January 1936, Kipling's ashes were buried in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey.[46]

3 of his poems ("A Dedication," "L'Envoi," and "Recessional") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900.[47]

Kipling's subsequent reputation has changed according to the political and social climate of the age[48][49] and the resulting contrasting views about him continued for much of the 20th century.[50][51] A young George Orwell called him a "prophet of British imperialism".[52] According to critic Douglas Kerr: "He is still an author who can inspire passionate disagreement and his place in literary and cultural history is far from settled. But as the age of the European empires recedes, he is recognised as an incomparable, if controversial, interpreter of how empire was experienced. That, and an increasing recognition of his extraordinary narrative gifts, make him a force to be reckoned with."[53]

In 2010, the International Astronomical Union approved that a crater on the planet Mercury would be named after Kipling - one of ten newly discovered impact craters observed by the MESSENGER spacecraft in 2008-9.[54]

Kipling is often quoted in discussions of contemporary political and social issues. Political singer-songwriter Billy Bragg, who attempts to reclaim English nationalism from the right-wing, has reclaimed Kipling for an inclusive sense of Englishness.[55] Kipling's enduring relevance has been especially noted in the United States as it has become involved in Afghanistan and other areas about which he wrote.[56][57][58]

Links with Scouting

Photograph of General Sir Ian Hamilton, commander of the ill-fated Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in the Battle of Gallipoli in the First World War, at Rudyard Kipling's funeral in 1936. Hamilton was a close personal friend of Kipling.

Kipling's links with the Scouting movements were strong. Baden-Powell, the founder of Scouting, used many themes from The Jungle Book stories and Kim in setting up his junior movement, the Wolf Cubs. These connections still exist today. Not only is the movement named after Mowgli's adopted wolf family, the adult helpers of Wolf Cub Packs adopt names taken from The Jungle Book, especially the adult leader who is called Akela after the leader of the Seeonee wolf pack.[59]

Kipling's home at Burwash

After the death of Kipling's wife in 1939, his house, "Bateman's" in Burwash, East Sussex was bequeathed to the National Trust and is now a public museum dedicated to the author. Elsie, the only one of his three children to live past the age of eighteen, died childless in 1976, and bequeathed her copyrights to the National Trust. There is a thriving Kipling Society in the United Kingdom and also one in Australia.

Sir Kingsley Amis wrote a poem entitled 'Kipling at Bateman's', which was the product of a visit to his house in Burwash - a village where Amis' father had lived briefly in the 1960s. Amis and a BBC television crew went to make a short film in a series of films about writers and their houses. According to Zachary Leader's 'The Life of Kingsley Amis':

'Bateman's made a strong negative impression on the whole crew, and Amis decided that he would dislike spending even twenty-four hours there. The visit is recounted in Rudyard Kipling and his World (1975), a short study of Kipling's Life and Writings. Amis's view of Kipling's career is like his view of Chesterton's: the writing that mattered was early, in Kipling's case from the period 1885-1902. After 1902, the year of the move to Bateman's, not only did the work decline but Kipling found himself increasingly at odds with the world, changes Amis attributes in part to the depressing atmosphere of the house.[60]

Reputation in India

In modern-day India, whence he drew much of his material, his reputation remains controversial, especially amongst modern nationalists and some post-colonial critics. Other contemporary Indian intellectuals such as Ashis Nandy have taken a more nuanced view of his work. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, 1st Prime Minister of India, always described Kipling's novel Kim as his favourite book.[61][62]

G V Desani, a canonical Indian writer of fiction, had a condescending opinion of Kipling. He alluded to Kipling in his novel, All About H. Hatterr, thus:

I happen to pick up R. Kipling's autobiographical "Kim."

Therein, this self-appointed whiteman's burden-bearing sherpa feller's stated how, in the Orient, blokes hit the road and think nothing of walking a thousand miles in search of something.

Well-known Indian historian and writer Khushwant Singh wrote in 2001 that he considers Kipling's If-- "the essence of the message of The Gita in English".[63] The text Singh refers to is the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Indian scripture.

In November 2007, it was announced that Kipling's birth home in the campus of the J J School of Art in Mumbai will be turned into a museum celebrating the author and his works.[64]

Swastika in old editions

A left-facing swastika

Covers of two of Kipling's books from 1919 (l) and 1930 (r)

Many older editions of Rudyard Kipling's books have a swastika printed on their covers associated with a picture of an elephant carrying a lotus flower. Since the 1930s this has raised the possibility of Kipling being mistaken for a Nazi-sympathiser, though the Nazi party did not adopt the swastika until 1920. Kipling's use of the swastika was based on the Indian sun symbol conferring good luck and well-being; the word derived from the Sanskrit word svastika meaning "auspicious object". He used the swastika symbol in both right- and left-facing orientations, and it was in general use at the time.[65][66] Even before the Nazis came to power, Kipling ordered the engraver to remove it from the printing block so that he should not be thought of as supporting them. Less than one year before his death Kipling gave a speech (titled "An Undefended Island") to The Royal Society of St George on 6 May 1935 warning of the danger Nazi Germany posed to the UK.[67]

In popular culture

His Jungle Books have been made into several movies. The earliest was made by producer Alexander Korda, and other films have been produced by the Walt Disney Company. A number of his poems were set to music by Percy Grainger. A series of short films based on some of his stories was broadcast by the BBC in 1964.[68]

Publications

- Main article: Rudyard Kipling bibliography

Poetry

- Schoolboy Lyrics. India: privately printed, 1881.

- Echoes: By two writers (with sister, Beatrice Kipling). Lahore, India: Civil and Military Gazette Press, 1884.

- Departmental Ditties and other verses.Lahore, India: Civil & Military Gazette Press, 1886

- 2nd edition, enlarged. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1886,

- 3rd edition, further enlarged, 1888

- 4th edition, still further enlarged. London: W. Thacker / Calcutta Thacker, Spink, 1890; 10th edition, 1898.

- Departmental Ditties, Barrack-Room Ballads, and other verses (contains the 50 poems of the fourth edition of Departmental Ditties and other verses and 17 new poems later published as Ballads and Barrack-Room Ballads). United States Book Co., 1890

- revised edition published as Departmental Ditties and Ballads and Barrack-Room Ballads. Doubleday McClure, 1899.

- Ballads and Barrack-Room Ballads. London: Macmillan, 1892

- new edition, with additional poems, 1893

- published as The Complete Barrack-Room Ballads of Rudyard Kipling (edited by Charles Carrington). Methuen, 1973; also published as Barrack Room Ballads, and other verses. White Rose Press, 1987.

- The Rhyme of True Thomas. New York: D. Appleton, 1894.

- The Seven Seas. New York: D. Appleton, 1896; Longwood Publishing Group, 1978.

- Recessional (Victorian ode in commemoration of Queen Victoria's Jubilee). M.F. Mansfield, 1897.

- Mandalay (drawings by Blanche McManus). M.F. Mansfield, 1898; Doubleday, Page, 1921.

- Verses 1889-1896. New York: Scribner, 1898.[69]

- The Betrothed (drawings by Blanche McManus). M.F. Mansfield and A. Wessells, 1899.

- Poems, Ballads, and other verses (illustrations by V. Searles)., H.M. Caldwell, 1899.

- Belts. A. Grosset, 1899.

- Cruisers. New York: Doubleday McClure, 1899.

- The Reformer. Doubleday, Page, 1901.

- The Lesson. Doubleday, Page, 1901.

- The Five Nations. Doubleday, Page, 1903.

- The Muse among the Motors. Doubleday, Page, 1904.

- The Sons of Martha. Doubleday, Page, 1907.

- Collected Verse of Rudyard Kipling. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Page, 1907; Toronto: Copp Clark, 1907.

- The City of Brass. Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- Cuckoo Song. Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- A Patrol Song. Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- A Song of the English (illustrations by W. Heath Robinson). Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- If. Doubleday, Page, 1910; reprinted, Doubleday, 1959.

- The Declaration of London. Doubleday, Page, 1911.

- The Spies' March. Doubleday, Page, 1911.

- Three Poems (contains "The River's Tale," "The Roman Centurion Speaks," and "The Pirates in England"). Doubleday, Page, 1911.

- Songs from Books. Doubleday, Page, 1912.

- An Unrecorded Trial. Doubleday, Page, 1913.

- For All We Have and Are. Methuen, 1914.

- The Children's Song. Macmillan, 1914.

- A Nativity. Doubleday, Page, 1917.

- A Pilgrim's Way. Doubleday, Page, 1918.

- The Supports. Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- The Years Between. Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- The Gods of the Copybook Headings. Doubleday, Page, 1919; reprinted, 1921.

- The Scholars. Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- Great-Heart. Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- Danny Deever. Doubleday, Page, 1921.

- The King's Pilgrimage. Doubleday, Page, 1922.

- Chartres Windows. Doubleday, Page, 1925.

- A Choice of Songs. Doubleday, Page, 1925.

- Sea and Sussex (with an introductory poem by the author and illustrations by Donald Maxwell). Doubleday, Page, 1926.

- A Rector's Memory. Doubleday, Page, 1926.

- Supplication of the Black Aberdeen (illustrations by G.L. Stampa). Doubleday, Doran, 1929.

- The Church That Was at Antioch. Doubleday, Doran, 1929.

- The Tender Achilles. Doubleday, Doran, 1929.

- Unprofessional. Doubleday, Page, 1930.

- The Day of the Dead. Doubleday, Doran, 1930.

- Neighbours. Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- The Storm Cone. Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- His Apologies (illustrations by Cecil Aldin). Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- The Fox Meditates. Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- To the Companions. Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- Bonfires on the Ice. Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- Our Lady of the Sackcloth. Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Hymn of the Breaking Strain. Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Doctors, The Waster, The Flight, Cain and Abel, [and] The Appeal. Doubleday, Doran, 1939.

- A Choice of Kipling's Verse (selected and introduced by T.S. Eliot). London: Faber, 1941; New York: Scribner, 1943.

- B.E.L.. Doubleday, Doran, 1944.

- Poems of Rudyard Kipling. Avenel, 1995.

Novels

- The Light That Failed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1891

- revised edition, Macmillan, 1891; reprinted, Penguin, 1988.

- The Naulahka: A Story of West and East (With Wolcott Balestier). Macmillan, 1892; reprinted, Doubleday, Page, 1925.

- Greenhow Hill. Philadelphia: Altemus, [1890's].[69]

- The Incarnation of Krishna Mulvaney. New York: Doubleday & McClure, 1899.[69]

- Kim (illustrations by father, J. Lockwood Kipling). Doubleday, Page, 1901

- new edition (illustrations by Stuart Tresilian). Macmillan, 1958

- reprinted (with introduction by Alan Sandison). Oxford University Press, 1987.

Short Fiction

- In Black and White. Allahabad, India: A.H. Wheeler, 1888; 1st American edition, Lovell, 1890.

- Plain Tales from the Hills. Thacker, Spink, 1888

- 2nd edition, revised, 1889

- 1st English edition, revised, Macmillan, 1890

- 1st American edition, revised, Doubleday McClure, 1899

- reprint (edited by H.R. Woudhuysen). Penguin, 1987.

- The Phantom 'Rickshaw, and other tales. A.H. Wheeler, 1888

- revised edition, 1890, reprinted, Hurst, 1901.

- Soldiers Three: A Collection of Stories Setting Forth Certain Passages in the Lives and Adventures of Privates Terence Mulvaney, Stanley Ortheris, and John Learoyd. A.H. Wheeler, 1888. Part I, Part II.

- 1st American edition, revised, Lovell, 1890; reprinted, Belmont, 1962.

- Under the Deodars. A.H. Wheeler, 1888

- 1st American edition, enlarged, Lovell, 1890.

- The Story of the Gadsbys: A tale with no plot. A.H. Wheeler, 1888; 1st American edition, Lovell, 1890.

- Indian Tales. New York: U.S. Book Co., 1890.[69]

- The Courting of Dinah Shadd and other stories (with a biographical and critical sketch by Andrew Lang). Harper, 1890; reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971.

- His Private Honour. Macmillan, 1891.

- The Smith Administration. A.H. Wheeler, 1891.

- Mine Own People (introduction by Henry James). United States Book Co., 1891.

- Life's Handicap: Being stories of mine own people. London & New York: Macmillan, 1901.

- Many Inventions. D. Appleton, 1893; reprinted, Macmillan, 1982.

- Mulvaney Stories, 1897; reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971.

- The Day's Work, Doubleday McClure, 1898; reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971

- reprinted (with introduction by Constantine Phipps). Penguin, 1988. Volume I

- Soldier Stories. London & New York: Macmillan, 1896.[69]

- The Drums of the Fore and Aft (illustrations by L.J. Bridgman). Brentano's, 1898.

- The Man Who Would Be King. Brentano's, 1898.

- Black Jack. F.T. Neely, 1899.

- Without Benefit of Clergy. Doubleday McClure, 1899.

- The Brushwood Boy (illustrations by Orson Lowell). Doubleday & McClure, 1899

- reprinted (with illustrations by F.H. Townsend). Doubleday, Page, 1907.

- Railway Reform in Great Britain. Doubleday, Page, 1901.

- Traffics and Discoveries. Doubleday, Page, 1904; reprinted, Penguin, 1987.

- They. Scribner, 1904.

- Abaft the Funnel. New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- Actions and Reactions. New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- With the Night Mail: A story of 2000 A.D.. New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- A Diversity of Creatures. Doubleday, Page, 1917; reprinted, Macmillan, 1966; reprinted, Penguin, 1994.

- "The Finest Story in the World" and other stories. Little Leather Library, 1918.

- Debits and Credits. Doubleday, Page, 1926; reprinted, Macmillan, 1965.

- Thy Servant a Dog, Told by Boots (illustrations by Marguerite Kirmse). Doubleday, Doran, 1930.

- Beauty Spots. Doubleday, Doran, 1931.

- Limits and Renewals. Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- The Pleasure Cruise. Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- Collected Dog Stories (illustrations by Kirmse). Doubleday, Doran, 1934.

- Ham and the Porcupine. Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Teem: A Treasure-Hunter. Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- The Maltese Cat: A Polo Game of the 'Nineties (illustrations by Lionel Edwards). Doubleday, Doran, 1936.

- "Thy Servant a Dog" and Other Dog Stories (illustrations by G.L. Stampa). Macmillan, 1938; reprinted, 1982.

- Their Lawful Occasions. White Rose Press, 1987.

- John Brunner Presents Kipling's Science Fiction: Stories. New York: T. Doherty Associates, 1992.

- John Brunner Presents Kipling's Fantasy: Stories. new York: T. Doherty Associates, 1992.

- The Man Who Would Be King, and other stories. Mineola, NY: Dover, 1994.

- The Science Fiction Stories of Rudyard Kipling. Carol, 1994.

- Collected Stories (edited by John Brunner). New York: Knopf, 1994.

- The Works of Rudyard Kipling. Longmeadow Press, 1995.

- The Haunting of Holmescraft. New York: Books of Wonder, 1998.

- The Mark of the Beast, and Other Horror Tales. Mineola, NY: Dover, 2000.

- The Metaphysical Kipling; Mamaroneck, NY: Aeon, 2000.

- L.L. Owens, Tales of Rudyard Kipling: Retold Timeless Classics. Logan, IA: Perfection Learning, 2000.

- Selected Stories of Rudyard Kipling (edited and introduction by Craig Raine). New York: Modern Library, 2002.

Juvenile

- "Wee Willie Winkie", and other child stories. A.H. Wheeler, 1888; 1st American edition, Lovell, 1890; reprinted, Penguin, 1988. [

- The Jungle Book (short stories and poems; illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling, W.H. Drake, and P. Frenzeny). Macmillan, 1894

- adapted and abridged by Anne L. Nelan (illustrations by Earl Thollander). Fearon, 1967

- reprinted (illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling and W.H. Drake)., Macmillan, 1982

- adapted by G.C. Barrett (illustrations by Don Daily). Courage Books, 1994

- reprinted (illustrations by Fritz Eichenberg), Grosset & Dunlap, 1995

- reprinted (illustrations by Kurt Wiese). New York: Knopf, 1994.

- The Second Jungle Book (short stories and poems; illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling). Century Co., 1895; reprinted, Macmillan, 1982.

- "Captains Courageous": A story of the Grand Banks. Century Co., 1897

- abridged edition (illustrated by Rafaello Busoni). Hart Publishing, 1960 **reprinted (with afterword by C.A. Bodelsen). New York: New American Library, 1981; reprinted, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Stalky & Co. (short stories). Doubleday McClure, 1899; reprinted, Bantam, 1985

- new and abridged edition, Pendulum Press, 1977.

- Just So Stories for Little Children (short stories and poems; illustrations by the author). Doubleday, Page, 1902; reprinted, Silver Burdett, 1986

- revised (edited by Lisa Lewis). Oxford University Press, 1995; reprinted (illustrations by Barry Moser). Books of Wonder, 1996.

- Puck of Pook's Hill (short stories and poems). Doubleday, 1906; reprinted, New American Library, 1988.

- Rewards and Fairies (short stories and poems; illustrations by Frank Craig). Doubleday, Page, 1910

- revised edition (illustrations by Charles E. Brock). Macmillan, 1926;, reprinted, Penguin, 1988.

- Toomai of the Elephants. Macmillan, 1937.

- The Miracle of Purun Bhagat. Creative Education, 1985.

- Gunga Din. Harcourt, 1987.

- Mowgli Stories from "The Jungle Book" (illustrated by Thea Kliros). Dover, 1994.

- The Elephant's Child (illustrated by John A. Rowe). North-South Books, 1995.

- The Beginning of the Armadillos (illustrated by John A. Rowe). North-South Books, 1995.

- How the Camel Got His Hump. New York: North-South Books, 2001.

- The Classic Tale of the Jungle Book: A Young Reader's Edition of the Classic Story. Philadelphia: Courage Books, 2003.

Non-fiction

Travel

- Letters of Marque. A.H. Wheeler, 1891.

- American Notes. M.J. Ivers, 1891; reprinted, Ayer Co., 1974

- revised edition published as American Notes: Rudyard Kipling's West. University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

- From Sea to Sea, and other sketches (2 volumes), Doubleday & McClure, 1899

- published as 1 volume. Doubleday, Page, 1909; reprinted, 1925.

- Letters to the Family: Notes on a Recent Trip to Canada. Toronton: Macmillan of Canada, 1908.

- Letters of Travel, 1892-1913. Doubleday, Page, 1920.

- Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides. London: Macmillan, 1923

- published as Land and Sea Tales for Boys and Girls. Doubleday, Page, 1923.

- Souvenirs of France. Macmillan, 1933.

- Brazilian Sketches. Doubleday, Doran, 1940.

- Letters from Japan (edited with an introduction and notes by Donald Richie and Yoshimori Harashima). Kenkyusha, 1962.

- A Fleet in Being: Notes of Two Trips With the Channel Squadron. London: Macmillan, 1899.

- The Army of a Dream. Doubleday, Page, 1904; reprinted, White Rose Press, 1987.

- The New Army. Doubleday, Page, 1914.

- The Fringes of the Fleet. Doubleday, Page, 1915.

- France at War: On the frontier of civilization. Doubleday, Page, 1915.

- Sea Warfare. Macmillan, 1916; Doubleday, Page, 1917.

- Tales of "The Trade". Doubleday, Page, 1916.

- The Eyes of Asia. Doubleday, Page, 1918.

- The Irish Guards. Doubleday, Page, 1918.

- The Graves of the Fallen. Imperial War Graves Commission, 1919.

- The Feet of the Young Men (photographs by Lewis R. Freeman). Doubleday, Page, 1920.

- The Irish Guards in the Great War: Edited and Compiled from Their Diaries and Papers (2 volumes). Doubleday, Page, 1923. Volume I: The First Battalion, Volume II: The Second Battalion and Appendices.

Other

- The City of Dreadful Night and other places (articles. A.H. Wheeler, 1891.

- Out of India: Things I Saw, and Failed to See, in Certain Days and Nights at Jeypore and Elsewhere (includes The City of Dreadful Night and Other Places and Letters of Marque). Dillingham, 1895.

- A History of England (With Charles R. L. Fletcher). Doubleday, Page, 1911

- published as Kipling's Pocket History of England (with illustrations by Henry Ford). Greenwich, 1983.

- How Shakespeare Came to Write "The Tempest" (introduction by Ashley H. Thorndike). Dramatic Museum of Columbia University, 1916.

- London Town: November 11, 1918-1923. Doubleday, Page, 1923.

- The Art of Fiction. J.A. Allen, 1926.

- A Book of Words: Selections from Speeches and Addresses Delivered between 1906 and 1927. Doubleday, Doran, 1928.

- Mary Kingsley. Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- Proofs of Holy Writ. Doubleday, Doran, 1934.

- Something of Myself for My Friends Known and Unknown (autobiography). Doubleday, Doran, 1937; reprinted, Penguin Classics, 1989.

Collected editions

- The Kipling Reader: Selections from the books of Rudyard Kipling. London & New York: Macmillan, 1900.[69]

- The Works of Rudyard Kipling: One volume edition. New York: Black's Readers Service, 1928.[69]

- The Portable Kipling (edited by Irving Howe). New York: Viking, 1982.

- Writings of Literature by Rudyard Kipling (edited by Sandra Kemp and Lisa Lewis). Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Writings on Writing (edited by Sandra Kemp and Lisa Lewis). Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Letters

- Rudyard Kipling to Rider Haggard: The Record of a Friendship (edited by Morton Cohen). Hutchinson, 1965.

- "O Beloved Kids": Rudyard Kipling's Letters to His Children (selected and edited by Elliot L. Gilbert). Harcourt, 1984.

- The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vols. 1-3 (edited by Thomas Pinney). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1990.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[70]

Poems by Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling - Tommy - poem

See also

References

- Allen, Charles (2007) Kipling Sahib: India and the Making of Rudyard Kipling, Abacus, 2007. ISBN 978-0-349-11685-3

- David, C. (2007). Rudyard Kipling: a critical study, New Delhi, Anmol, 2007. ISBN 81-261-3101-2

- Gilbert, Elliot L. ed., (1965) Kipling and the Critics (New York: New York University Press)

- Gilmour, David. (2003) The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374528969

- Green, Roger Lancelyn, ed., (1971) Kipling: the Critical Heritage (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul).

- Gross, John, ed. (1972) Rudyard Kipling: the Man, his Work and his World (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson)

- Kemp, Sandra. (1988) Kipling's Hidden Narratives Oxford: Blackwell* Lycett, Andrew (1999). Rudyard Kipling. London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81907-0

- Lycett, Andrew (ed.) (2010). Kipling Abroad, I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-072-9

- Ricketts, Harry. (2001) Rudyard Kipling: A Life New York: Da Capo Press ISBN 0786708301

- Rooney, Caroline, and Kaori Nagai, eds. Kipling and Beyond: Patriotism, Globalisation, and Postcolonialism (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 214 pages; scholarly essays on Kipling's "boy heroes of empire," Kipling and C.L.R. James, and Kipling and the new American empire, etc.

- Rutherford, Andrew, ed. (1964) Kipling's Mind and Art (Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd)

- Shippey, Tom, "Rudyard Kipling," in: Cahier Calin: Makers of the Middle Ages. Essays in Honor of William Calin, ed. Richard Utz and Elizabeth Emery (Kalamazoo, MI: Studies in Medievalism, 2011), pp. 21-23.

- Tompkins, J. M. S. (1959) The Art of Rudyard Kipling (London : Methuen) online edition

- Wilson, Angus The Strange Ride of Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Works New York: The Viking Press, 1978. ISBN 0-670-67701-9

Notes

- ↑ "Rudyard Kipling", Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., Britannica.com, Web, May 18, 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Rutherford, Andrew (1987). General Preface to the Editions of Rudyard Kipling, in "Puck of Pook's Hill and Rewards and Fairies", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282575-5

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Rutherford, Andrew (1987). Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of "Plain Tales from the Hills", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281652-7

- ↑ James Joyce considered Tolstoy, Kipling and D'Annunzio to be the "three writers of the nineteenth century who had the greatest natural talents", but that "he did not fulfill that promise". He also noted that the three writers all "had semi-fanatic ideas about religion, or about patriotism." Diary of David Fleischman, 21 July 1938, quoted in James Joyce by Richard Ellmann, p. 661, Oxford University Press (1983) ISBN 0-19-281465-6

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Carrington, C.E. (Charles Edmund). 1955. Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work. Macmillan and Company, London and New York.

- ↑ Flanders, Judith. 2005. A Circle of Sisters: Alice Kipling, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Agnes Poynter, and Louisa Baldwin. W.W. Norton and Company, New York. ISBN 0-393-05210-9

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 Gilmour, David. 2002. The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York.

- ↑ thepotteries.org (2002-01-13). "did you know ....". The potteries.org. http://www.thepotteries.org/did_you/002.htm. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ↑ Sir J.J. College of Architecture (2006-09-30). "Campus". Sir J. J. College of Architecture, Mumbai. http://www.sirjjarchitecture.org/v2/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=21&Itemid=30. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ↑ "To the City of Bombay", dedication to Seven Seas, by Rudyard Kipling, Macmillan and Company, 1894.

- ↑ Murphy, Bernice M. (1999-06-21). "Rudyard Kipling - A Brief Biography". School of English, The Queen's University of Belfast. http://www.qub.ac.uk/schools/SchoolofEnglish/imperial/india/kipling-bio.htm. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 Kipling, Rudyard (1935). "Something of myself". public domain. http://ghostwolf.dyndns.org/words/authors/K/KiplingRudyard/prose/SomethingOfMyself/index.html. Retrieved 2008-09-06.also: 1935/1990. Something of myself and other autobiographical writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40584-X.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Carpenter, Humphrey and Mari Prichard. 1984. Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. pp. 296-297.

- ↑ Pinney, Thomas (editor). Letters of Rudyard Kipling, volume 1. Macmillan and Company, London and New York.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard (1956) Kipling: a selection of his stories and poems, Volume 2 pp.349 Doubleday, 1956

- ↑ Robert D. Kaplan (1989) Lahore as Kipling Knew It. The New York Times. Retrieved on 9 March 2008

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard (1996) Writings on Writing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44527-2. see p. 36 and p. 173

- ↑ Mallet, Phillip. 2003. Rudyard Kipling: A Literary Life. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ISBN 0-333-55721-2

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ricketts, Harry. 1999. Rudyard Kipling: A life. Carroll and Graf Publishers Inc., New York. ISBN 0-7867-0711-9.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard. 1920. Letters of Travel (1892-1920). Macmillan and Company.

- ↑ Nicholson, Adam. 2001. Carrie Kipling 1862-1939 : The Hated Wife. Faber & Faber, London. ISBN 0-571-20835-5

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Pinney, Thomas (editor). Letters of Rudyard Kipling, volume 2. Macmillan and Company, London and New York.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard. 1899. The White Man's Burden. Published simultaneously in The Times, London, and McClure's Magazine (U.S.) 12 February 1899.

- ↑ Snodgrass, Chris. 2002. A Companion to Victorian Poetry. Blackwell, Oxford.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard. 1897. Recessional. Published in The Times, London, July 1897.

- ↑ Carrington, C. E., (1955) The life of Rudyard Kipling, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, N.Y., p. 236.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard (18 March 1900). "Kipling at Cape Town: Severe Arraignment of Treacherous Afrikanders and Demand for Condign Punishment By and By" (PDF). The New York Times: p. 21. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9401EFDC1339E733A2575BC1A9659C946197D6CF

- ↑ Carrington, C. E., (1955) The life of Rudyard Kipling, p. 286.

- ↑ mt (2005-11-17). "Link to National Trust Site for Bateman House". Nationaltrust.org.uk. http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-batemans. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ The Fringes of the Fleet, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., London, 1916

- ↑ Bennett, Arnold (1917). Books and Persons Being Comments on a Past Epoch 1908-1911. London: Chatto & Windus.

- ↑ Short Stories from the Strand, The Folio Society, 1992.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Literature 1907 - Presentation Speech". Nobelprize.org. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1907/press.html. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ "If, poem by Rudyard Kipling". Best Poems Encyclopedia. http://www.best-poems.net/rudyard_kipling/if.html.

- ↑ Mackey, Albert G. (1946). Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, Vol. 1. Chicago: The Masonic History Company.

- ↑ Mackey, above.

- ↑ By John Quinlan writing to National Inventory on War Memorials viewed at: http://ukniwm.wordpress.com/2007/12/11/the-controversy-over-john-kiplings-burial-place/

- ↑ Webb, George. Foreword to: Kipling, Rudyard. The Irish Guards in the Great War. 2 vols. (Spellmount, 1997), p. 9.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard. The Irish Guards in the Great War. 2 vols. (London, 1923)

- ↑ Original correspondence between Kipling and Maurice Hammoneau and his son Jean Hammoneau concerning the affair at the Library of Congress under the title: How "Kim" saved the life of a French soldier : a remarkable series of autograph letters of Rudyard Kipling, with the soldier's Croix de Guerre, 1918-1933. (LOC Ref#2007566938) [1]. The library also possesses the actual French 389-page paperback edition of Kim that saved Hammoneau's life, (LOC Ref 2007581430) [2]

- ↑ "The Iron Ring<!- Bot generated title ->". Ironring.ca. http://www.ironring.ca/. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Rudyard Kipling's Waltzing Ghost: The Literary Heritage of Brown's Hotel, paragraph 11, Sandra Jackson-Opoku, Literary Traveler

- ↑ T.S. Eliot, Introduction to A Choice of Kipling's Verse (London: Faber, 1941), 6, Print.

- ↑ Alfred Nobel Foundation. "Who is the youngest ever to receive a Nobel Prize, and who is the oldest?". Nobelprize.com. p. 409. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25. http://web.archive.org/web/20060925202706/http://nobelprize.org/contact/faq/index.html#3b. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ↑ Birkenhead, Lord. 1978. Rudyard Kipling, Appendix B, 'Honours and Awards'. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London; Random House Inc., New York.

- ↑ Rudyard Kipling, People, History, Westminster Abbey. Web, July 12, 2016.

- ↑ Alphabetical list of authors: Jago, Richard to Milton, John. Arthur Quiller-Couch, editor, Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919). Bartleby.com, Web, May 18, 2012.

- ↑ Lewis, Lisa. 1995. Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of "Just So Stories", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. pp.xv-xlii. ISBN 0-19-282276-4

- ↑ Quigley, Isabel. 1987. Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of "The Complete Stalky & Co.", by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. pp.xiii-xxviii. ISBN 0-19-281660-8

- ↑ Said, Edward. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto & Windus. Page 196. ISBN 0-679-75054-1.

- ↑ Sandison, Alan. 1987. Introduction to the Oxford World's Classics edition of Kim, by Rudyard Kipling. Oxford University Press. pp. xiii-xxx. ISBN 0-19-281674-8.

- ↑ Orwell, George (2006-09-30). "Essay on Kipling". http://www.george-orwell.org/Rudyard_Kipling/0.html. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ↑ Douglas Kerr, University of Hong Kong. "Rudyard Kipling." The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 May. 2002. The Literary Dictionary Company. 26 September 2006. [3]

- ↑ - Article from the Red Orbit News network 16 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Rhyme and Reason, BBC Radio 4, 25 January 2011

- ↑ WORLD VIEW: Is Afghanistan turning into another Vietnam?, Johnathan Power, The Citizen, December 31, 2010

- ↑ Is America waxing or waning?, Andrew Sullivan, The Atlantic, December 12, 2010

- ↑ Rudyard Kipling, Official Poet of the 911 War

- ↑ "ScoutBase UK: The Library - Scouting history - Me Too! - The history of Cubbing in the United Kingdom 1916-present<!- Bot generated title ->". Scoutbase.org.uk. http://www.scoutbase.org.uk/library/history/cubs/index.htm#Jungle. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ 'The Life of Kingsley Amis', Zachary Leader, Vintage, 2007 pp.704-705

- ↑ Globalization and educational rights: an intercivilizational analysis, Joel H. Spring, pg.137

- ↑ Post independence voices in South Asian writings, Malashri Lal, AlamgÄ«r HashmÄ«, Victor J. Ramraj, 2001. «Not surprisingly, a brief biographical aside practically identifies Nehru with Kim»

- ↑ Khushwant Singh, Review of The Book of Prayer by Renuka Narayanan , 2001

- ↑ "Kipling's India home to become museum". BBC News. 2007-11-27. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/7095922.stm. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ Schliemann, H, Troy and its remains, London: Murray, 1875, pp. 102, 119-120

- ↑ Sarah Boxer. "One of the world's great symbols strives for a comeback". The New York Times, July 29, 2000.

- ↑ Rudyard Kipling, War Stories and Poems (Oxford Paperbacks, 1999), pp. xxiv-xxv.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0298668/

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 69.4 69.5 69.6 Rudyard Kipling, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Sep. 13, 2013.

- ↑ Rudyard Kipling 1865-1936, Poetry Foundation, Web, Oct. 25, 2012.

External Links

- Poems

- Rudyard Kipling in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900: "A Dedication," "L'Envoi," "Recessional".

- 4 poems by Kipling: "Rudyard Kipling," "A Song to Mithras," "Puck's Song," "The Way Through the Woods"

- Rudyard Kipling 1865-1936 at the Poetry Foundation

- Kipling in A Victorian Anthology: "Danny Deever," "Fuzzy-Wuzzy," "The Ballad of East and West," "The Conundrum of the Workshops," "The Law for the Wolves," "The Last Chantey"

- Rudyard Kipling profile & 9 poems at the Academy of American Poets.

- Selected Poetry of Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) (25 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- Rudyard Kipling at PoemHunter (544 poems).

- Complete Collection of Poems by Rudyard Kipling at Poetry Lovers' Page.

- Books

- Works by Rudyard Kipling at Project Gutenberg, HTML online, text download.

- Rudyard Kipling at the Online Books Page

- Works by Rudyard Kipling at Internet Archive, scanned books viewable online or PDF download.

- The Works of Rudyard Kipling at The University of Adelaide

- Works by or about Rudyard Kipling in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Works by Rudyard Kipling, HTML online.

- Many works by Rudyard Kipling available at ReadmeFree

- Something of Myself, Kipling's autobiography

- Rudyard Kipling at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Audio / video

- Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) at The Poetry Archive

- KIM free mp3 recording from LibriVox.org.

- Kipling reads 7 lines from his poem France audio and full text of poem.

- Rudyard Kipling at YouTube

- About

- Rudyard Kipling biography at NobelPrize.org.

- Rudyard Kipling in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Rudyard Kipling at NNDB

- Rudyard Kipling at Biography.com

- Rudyard Kipling at the Victorian Web

- Rudyard Kipling at Project Gutenberg, by John Palmer, 1915 biography

- Rudyard Kipling at Naulakha, by Charles Warren Stoddard, National Magazine, June 1905, with photos

- Discovery that keeps Kipling's soul in torment, Afternmath

- Etc.

- The Kipling Society Official website.

- Rudyard Kipling: The Books I Leave Behind exhibition, related podcast, and digital images maintained by the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

| This page uses content from Wikinfo . The original article was at Wikinfo:Rudyard Kipling. The list of authors can be seen in the (view authors). page history. The text of this Wikinfo article is available under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license. |

| |||||||||||||||||||

|