Thomas Middleton, 1580-1627), from Two New Plays, 1657. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Middleton (baptized 18 April 1580 - 4 July 1627)[1] was an English poet and playwright.

Life[]

Overview[]

Who was Thomas Middleton? - The Scholemaster

Middleton was a Londoner and city chronologer, in which capacity he composed a chronicle of the city, now lost. He wrote over 20 plays, chiefly comedies, besides masques and pageants, and collaborated with Dekker, Webster, and other playwrights. His best plays are The Changeling, The Spanish Gipsy (both with Rowley), and Women beware Women. Another, The Game of Chess (1624), got the author and the players alike into trouble on account of its having brought the King of Spain and other public characters upon the stage. They, however, got off with a severe reprimand. Middleton was a keen observer of London life, and shone most in scenes of strong passion. He is, however, unequal and repeats himself.[2]

Middleton stands with John Fletcher and Ben Jonson as among the most successful and prolific of playwrights who wrote their best plays during the Jacobean period. He was 1 of the few Renaissance dramatists to achieve equal success in comedy and tragedy. Also a prolific writer of masques and pageants, he remains 1 of the most noteworthy and distinctive of Jacobean dramatists.[3]

Youth and education[]

Middleton was born in London,[4] and baptized on 18 April 1580. He was the son of a bricklayer who had raised himself to the status of a gentleman and who, interestingly, owned property adjoining the Curtain theatre in Shoreditch.[3]

Middleton was just 5 when his father died, and his mother's subsequent remarriage dissolved into a 15-year battle over the inheritance of Thomas and his younger sister: an experience which must surely have informed and perhaps even incited his repeated satirising of the legal profession.[3]

Middleton attended Queen’s College, Oxford, matriculating in 1598, although he did not graduate. Before he left Oxford (sometime in 1600 or 1601[5]), he wrote and published 3 long poems in popular Elizabethan styles; none appears to have been especially successful, and his book of satires ran afoul of the Anglican Church's ban on verse satire and was burned. Nevertheless, his literary career was launched.[3]

Career[]

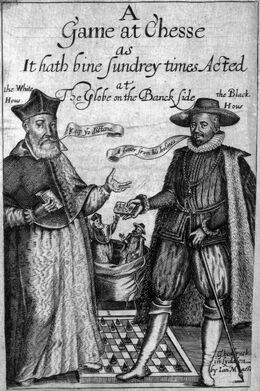

Title page of Middleton's "A Game of Chess", from Thomas Middleton, Collected Works. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Middleton began to write for the stage with The Old Law, in the original draft of which, if it dates from 1599 as is generally supposed, he was certainly not associated with William Rowley and Philip Massinger, although their names appear on the title-page of 1656.[6]

By 1602 he had become one of Philip Henslowe's established playwrights. The pages of Henslowe's Diary contain notes of plays in which he had a hand, and in the year 1607-1608 he produced no less than 6 comedies of London life, which he knew as accurately as Dekker and was content to paint in more realistic colors.[6]

In 1613 he devised the pageant for the installation of the Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Middleton, and in the same year wrote an entertainment for the opening of the New River in honour of another Middleton. From these facts it may be reasonably inferred that he had influential connections. He was frequently employed to celebrate civic occasions, and in 1620 he was made city chronologer, performing the duties of his position with exactness till his death.[6]

Middleton worked with various authors, but his happiest collaboration was with William Rowley, this literary partnership being so close that F.G. Fleay (Biog. Chron. of the Drama) treats the dramatists together.[6]

The most notable event in his career was the production at the Globe theatre in 1624 of a political play, A Game at Chess, satirizing the policy of the court, which had just received a rebuff in the matter of the Spanish marriage, the English and Spanish personages concerned being disguised as the White Knight, the Black King, and so forth. The play was stopped, in consequence of remonstrances from the Spanish ambassador, but not until after 9 days' performances, and the dramatist and the actors were summoned to answer for it. It is doubtful whether Middleton was actually imprisoned, and in any case the king's anger was soon satisfied and the matter allowed to drop, on the plea that the piece had been seen and passed by the master of the revels, Sir Henry Herbert.[6]

Middleton died at his house at Newington Butts, and was buried on 4 July 1627.[6]

Writing[]

Middleton's plays are marked by their cynicism about the human race, which is often very funny. True heroes are a rarity: almost every character is selfish, greedy, and self-absorbed. A Chaste Maid in Cheapside offers a panoramic view of a London populated entirely by sinners, in which no social rank goes unsatirised. In the tragedies Women Beware Women and The Revenger's Tragedy, amoral Italian courtiers endlessly plot against each other, resulting in a climactic bloodbath. When Middleton does portray good people, the characters have small roles and are presented as flawless. Due to a theological pamphlet attributed to him, Middleton is thought by some to have been a strong believer in Calvinism.[3]

Collaboration with Rowley[]

The plays in which Middleton and Rowley collaborated are A Fair Quarrel (printed 1617); The World Lost at Tennis(1620), an ingenious masque; The Changeling (acted 1624, printed 1653); and The Spanish Gipsie (acted. 1623, printed 1653). The main interest of the Fair Quarrel centers in the mental conflict of Captain Ager, the problem being whether he should fight in defense of his mother's honour when he no longer believes his quarrel to be just. The under plot, dealing with Jane, her concealed marriage, and the physician, which is generally assigned to Rowley, was suggested by a story in Giraldi Cinthio's Hecatommithi.[6]

The Changeling is the most powerful of all the plays with which Middleton's name is connected. The plot is drawn from the tale of Alsemero and Beatrice-Ioanna in Reynolds's Triumphs of God's Reveng against Murther (bk. i., hist. iv.), but the story, black as it is, receives additional horror in Middleton's hands. Leigh Hunt thought that the character of De Flores, for effect at once tragical, probable and poetical, “surpassed anything with which he was acquainted in the drama of domestic life.” The under plot of the piece, though it is based on the humors of a madhouse, has genuine comic flashes.[6]

The famous scene in the 3rd act between Beatrice and De Flores, who has murdered Piracquo at her instigation, is admirably described by Swinburne:

- That note of incredulous amazement that the man whom she has just instigated to the commission of murder can be so wicked as to have served her end for any end of his own beyond the pay of a professional assassin, is a touch worthy of the greatest dramatist that ever lived .... That she, the first criminal, should be honestly shocked aswell as physically horrified by revelation of the real motive which impelled her accomplice into crime, gives a lurid streak of tragic humour to the lifelike interest of the scene; as the pure infusion of spontaneous poetry throughout redeems the whole work from the charge of vulgar subservience to a vulgar taste for the presentation or the contemplation of criminal horror.[6]

The Spanish Gipsie has a double plot based on the Fuerza de la sangre and the Gitanilla of Cervantes.[6]

Much has been said on the collaboration of Middleton with Rowley, who was much in "demand with fellowf dramatists, especially for his experience in low comedy. These plays, even in scenes where the evidence in favor of either collaborator is clear, rise to excellence which neither dramatist was able to achieve alone. It was clearly no mechanical partnership the limits of which can be said to be definitely assigned when the actual text has been parcelled out between the collaborators.[6]

Collaboration with Dekker[]

With Thomas Dekker he wrote The Roaring Girle; or. Moll Cut-Purse (1611). The frontispiece represents Moll herself in man's attire, indulging in a pipe of tobacco, She was drawn or idealized from life, her real name being Mary Frith (1584-1659 P), who was made to do penance at St Paul's Cross 1612. "Worse things, I must confess," says Middleton in his preface, "the world has taxed her for than has been written of her; but 'tis the excellency of a writer to leave things better than he finds 'em.” In the play she is the champion of her sex, and is equally ready with her sword and her wits.[6]

Middleton is also credited with a share in Dekker's Honest Whore (pt. i., 1604).[6]

Other plays[]

The Witch, 1st printed in 1778 from a unique MS., now in the Bodleian, has aroused much controversy as to whether Shakespeare borrowed from Middleton or vice versa. The dates of both plays being uncertain, there are few definite data. The distinction between the 2 conceptions has been finely drawn by Charles Lamb, and the question of borrowing is best solved by supposing that what is common to the incantations of both plays was a matter of common property.[6]

The Mayor of Quinborough was published with Middleton's'name on the title-page in 1661. Simon, the comic mayor, is not a very prominent character in the plot, which deals with Vortiger, Hengist, Horsus and Roxenai among other characters. One of its editors, Havelock Elli, thinks the proofs of its authenticity as Middleton's work very slender. It is generally supposed to have been a very early work subjected to generous revision.[6]

The plays of Middleton still to be mentioned may be divided into romantic and realistic comedies of London Life. Dekker had as wide a knowledge of city manners, but he was more sympathetic in treatment, readier to idealize his subject. Two New Playes. Viz.: More Dissemblers besides Women / Women beware Women, of which the former was licensed before 1622, appeared in 1657. The plot of Women beware Women is a double intrigue from a contemporary novel, Hyppolito and Isabella, and the genuine history of Bianca Capello and Francesco de Medici. This play, which ends with a massacre appalling even in Elizabethan drama, may be taken as giving the measure of Middleton's unaided power in tragedy.[6]

The remaining plays of Middleton are: Blurt. Master-Constable. Or the Spaniards Night-walke (1602); Michaetmas Terme (1607), described by A. C. Swinburne as an excellent Hogarthian comedy; The Phoenix (1607), a version of the Haroun-al-Raschid trick; The Famelie of Looe (1608); A Trick to catch the Old-one (anonymously printed, 1608); Your Five Gallants (licensed 1608); A Mad World, my Masters (1608); A Chast Mayde in Cheapside (printed 1650), notable for the picture of Tim, the Cambridge student, on his return home; Anything for a Quiet Life (c. 1617, printed 1662); No Wit, No Help like a Woman's (c. I6[3, printed 1657): The Widdow (printed 1652), on the title-page of which appear also the names of Ben Jonson and John Fletcher, though their collaboration may be doubted. Eleven of his masques are extant.

Miscellaneous[]

A tedious poem, The Wisdom of Solomon; paraphrased, by Thomas Middleton, was printed in 1597, and Microcynicon: Six snarling satires by T.M. Gent, in 1599. 2 prose pamphlets dealing with London life, Father Hubbard's Tale and The Black Book, appeared in 1604 under his initials. His non-dramatic work, however, even if genuine, has little value.[6]

His works were edited by Alexander Dyce in 5 volumes in 1840, with a valuable introduction quoting many documents, and by A.H. Bullen in 8 volumes in 1885. The Best Plays of Thomas Middleton were edited for the Mermaid Series (1887) by Havelock Ellis with an introduction by Swinburne.[7]

Critical reputation[]

Middleton's plays have long been praised by literary critics, among them A.C. Swinburne and T.S. Eliot. The latter considered Middleton surpassed only by Shakespeare. In his own time, Middleton was thought talented enough to revise Shakespeare's Macbeth and Measure for Measure.[3]

Recognition[]

Middleton's plays were staged through the 20th century and into the 21st, each decade offering more productions than the last. Even less familiar works have been staged: A Fair Quarrel was performed at the National Theatre; The Old Law has been performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company, , and the tragedy Women Beware Women remains a stage favorite.[3]

In popular culture[]

The Changeling has been adapted for film several times. The Revenger's Tragedy was adapted into Alex Cox's film Revengers Tragedy, the opening credits of which attribute the play's authorship to Middleton.[3]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Wisdom of Solomon Paraphrased. London: Valentine

Sems [Simmes], 1597.

- Microcynicon: Six snarling satires. London: Thomas Creede, for Thomas Bushell, 1599.

- The Ghost of Lucrece. London: Valentine Simmes, 1600.

Plays[]

- Blurt, Master-constable. London: Henry Rockytt, 1602.

- The Honest Whore. London: Valentine Simmes et al, for Iohn Hodgets, 1604.

- The Magnificent Entertainment. London: T.C., for Tho. Man the yonger, 1604.

- Michaelmass Terme. London: Thomas Purfoot & Edward Allde, for Arthur Iohnson, 1607.

- The Phoenix. London: Edward Allde, for Arthur Iohnson, 1607.

- The Familie of Love. London: Richard Bradock, for Iohn Helmes, 1608.

- A Mad World, My Masters. London: H. Ballard, for Walter Burre, 1608.

- A Tricke to Catch the Olde One. London: George Eld, for Henry Rockytt, 1608.

- Your Five Gallants. London: Richard Bonian, 1608.

- The Roaring Girle; or, Moll Cut-purse. London: Nicholas Okes, for Thomas Archer, 1611.

- The Manner of His Lordships Entertainment on Michaelmas day Last. London: Nicholas Okes, 1613.

- The Triumphs of Truth. London: Nicholas Okes, 1613.

- Civitatis Amor, the Cities Love: An entertainment. London: Nicholas Okes, for Thomas Archer, 1616.

- The Tryumphs of Honor and Industry: A solemnity. London: Nicholas Okes, 1617

- The Inner-Temple Masque; or, Masque of heroes. London: John Browne, 1619.

- The Triumphs of Loue and Antiquity. London: Nicholas Okes, 1619.

- A Courtly Masque: The device called the World tost at tennis. London: George Purslowe, for Edward Wright, 1620.

- Honorable entertainments: Compos'd for the service of this noble cittie. 1621.

- The Sun in Aries: A noble solemnity. Ed. Allde, for H.G., 1621.

- A Faire Quarrell. London: 1622.

- The Triumphs of Honour and Vertue. London: 1622.

- A game at chess. London: 1625.

- The Triumphs of Health and Prosperity. London: Nicholas Okes, 1626.

- A Chast Mayd in Cheape-side: A pleasant conceited comedy. London: Francis Constable, 1630.

- The Widdow: A comedie. London: Humphrey Moseley, 1652.

- The Changeling (with William Rowley). London: Humphrey Moseley, 1653.

- The Spanish Gipsie. I.G., for Richard Marriot, 1653.

- The Excellent Comedy called, The old law. London: Edward Archer, 1656.

- No Wit Like a Womans: A comedy. London: Thomas Newcombe, for Humphrey Moseley, 1657.

- Two New Plays; viz., More dissemblers besides women; Women beware women. London: Humphrey Moseley, 1657.

- The Mayor of Quinborough: A comedy. London: Henry Herringman, 1661.

- Any Thing for a Quiet Life: A comedy. London: Tho. Johnson, for Francis Kirkman / Henry Marsh, 1662.

- A Tragi-coomodie called The Witch. London: J. Nichols, 1778.

- Selected Plays. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Short fiction[]

- The Ant and the Nightengale; or, Father Hubburds tales. London: Thomas Creede, for Tho. Bushell, 1604.

Non-fiction[]

- The Meeting of Gallants at an Ordinary (with Thomas Dekker). London: T. Creede. for Mathew Lawe, 1604.

- The Blacke Book. London: T.C.. for Ieffrey Chorlton, 1604.

- Sir Robert Sherley His Entertainment in Cracovia. London : Printed by I. Windet, for Iohn Budge, 1609.

- The Two Gates of Salvation. 1609

- also printed as The Mariage of the Old and New Testament. London: Nicholas Okes, 1620.

- The Peace-Maker; or, Great Brittaines blessing. London: Thomas Purfoot, 1619.

Collected editions[]

- Works (edited by A.H. Bullen). (8 volumes), London: Nimmo, 1885-1886; New York: AMS Press, 1964.

- Thomas Middleton (edited by Havelock Ellis & Algernon Charles Swinburne). London: Vizetelly, 1887; London: T.F. Unwin / New York: Scribner, 1887.

- The Collected Works (edited by Gary Taylor & John Lavagnino). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press / New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[8]

Plays performed[]

Note: The Middleton canon is beset by complications involving collaboration and debated authorship. The most recent and authoritative Middleton canon has been established by the editors of the Oxford Middleton (2007). All dates of plays are dates of composition, not of publication.

- The Phoenix (1603–4)

- The Honest Whore, Part 1, a city comedy (1604), co-written with Thomas Dekker

- Michaelmas Term, a city comedy, (1604)

- A Trick to Catch the Old One, a city comedy (1605)

- A Mad World, My Masters, a city comedy (1605)

- A Yorkshire Tragedy, a 1-act tragedy (1605); attributed to Shakespeare on its title page, but stylistic analysis favours Middleton.

- Timon of Athens a tragedy (1605–1606); stylistic analysis indicates that Middleton may have written this play in collaboration with William Shakespeare.

- The Puritan (1606)

- The Revenger's Tragedy (1606). Earlier editions often attribute authorship to Cyril Tourneur.

- Your Five Gallants, a city comedy (1607)

- The Bloody Banquet (1608–9); co-written with Thomas Dekker.

- The Roaring Girl, a city comedy depicting the exploits of Mary Frith (1611); co-written with Thomas Dekker.

- No Wit, No Help Like a Woman's, a tragicomedy (1611)

- The Second Maiden's Tragedy, a tragedy (1611); an anonymous manuscript; stylistic analysis indicates Middleton's authorship (though one scholar, Charles Hamilton, has attributed it to Shakespeare; see The History of Cardenio for details).

- A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, a city comedy (1613)

- Wit at Several Weapons, a city comedy (1613); printed as part of the Beaumont and Fletcher Folio, but stylistic analysis indicates comprehensive revision by Middleton and William Rowley.

- More Dissemblers Besides Women, a tragicomedy (1614)

- The Widow (1615–16)

- The Witch, a tragicomedy (1616)

- Macbeth, a tragedy. Various evidence indicates that the extant text of Shakespeare's Macbeth was partly adapted by Middleton in 1616, using passages from The Witch.

- A Fair Quarrel, a tragicomedy (1616). Co-written with William Rowley.

- The Old Law, a tragicomedy (1618–19). Co-written with William Rowley and perhaps a 3rd collaborator, who may have been Philip Massinger or Thomas Heywood.

- Hengist, King of Kent, or The Mayor of Quinborough, a tragedy (1620)

- Women Beware Women, a tragedy (1621)

- Measure for Measure. Stylistic evidence indicates that the extant text of Shakespeare's Measure for Measure was partly adapted by Middleton in 1621.

- Anything for a Quiet Life, a city comedy (1621). Co-written with John Webster.

- The Changeling, a tragedy (1622). Co-written with William Rowley.

- The Nice Valour (1622). Printed as part of the Beaumont and Fletcher Folio, but stylistic analysis indicates comprehensive revision by Middleton.

- The Spanish Gypsy, a tragicomedy (1623). Believed to be a play by Middleton and William Rowley revised by Thomas Dekker and John Ford.

- A Game at Chess, a political satire (1624). Satirized the negotiations over the proposed marriage of Prince Charles, son of James I of England, with the Spanish princess. Closed after 9 performances.

Masques and entertainments[]

- The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment Given to King James Through the City of London (1603–4). Co-written with Thomas Dekker, Stephen Harrison and Ben Jonson.

- The Manner of his Lordship's Entertainment

- The Triumphs of Truth

- Civitas Amor

- The Triumphs of Honour and Industry (1617)

- The Masque of Heroes, or, The Inner Temple Masque (1619)

- The Triumphs of Love and Antiquity (1619)

- The World Tossed at Tennis (1620). Co-written with William Rowley.

- Honourable Entertainments (1620–1)

- An Invention (1622)

- The Sun in Aries (1621)

- The Triumphs of Honour and Virtue (1622)

- The Triumphs of Integrity with The Triumphs of the Golden Fleece (1623)

- The Triumphs of Health and Prosperity (1626)

See also[]

The Revenger's Tragedy

References[]

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Middleton, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 416-417.. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 13, 2018.

- Covatta, Anthony. Thomas Middleton's City Comedies. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1973.

- Barbara Jo Baines. The Lust Motif in the Plays of Thomas Middleton. Salzburg, 1973.

- Eccles, Mark (1933). "Middleton's Birth and Education". Review of English Studies 7: 431–41.

- J.R. Mulryne, Thomas Middleton ISBN 0-582-01266-X

- Pier Paolo Frassinelli. "Realism, Desire, and Reification: Thomas Middleton's 'A Chaste Maid in Cheapside'." Early Modern Literary Studies 8 (2003).

- Kenneth Friedenreich, editor, "Accompaninge the players": Essays Celebrating Thomas Middleton, 1580–1980 ISBN 0-404-62278-X

- Margot Heinemann. Puritanism and Theatre: Thomas Middleton and Opposition Drama Under the Early Stuarts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Herbert Jack Heller. Penitent Brothellers: Grace, Sexuality, and Genre in Thomas Middleton's City Comedies. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Press, 2000.

- Bryan Loughrey and Neil Taylor. "Introduction." In Thomas Middleton, Five Plays. Bryan Loughrey and Neil Taylor, eds. Penguin, 1988.

- Schoenbaum, Samuel (1956). "Middleton's Tragicomedies". Modern Philology 54: 7–19. doi:10.1086/389120.

- Ceri Sullivan, ‘Thomas Middleton’s View of Public Utility’, Review of English Studies 58 (2007), pp. 160–74.

Notes[]

- ↑ Thomas Middleton, NNDB. Web, Aug. 20,2016.

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Middleton, Thomas," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 268. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 12, 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Thomas Middleton, Wikipedia, February 7, 2018, Wikimedia Foundation. Web, Feb. 13, 2018.

- ↑ Thomas Middleton, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Web, Aug. 20, 2016.

- ↑ Mark Eccles, "Thomas Middleton a Poett', "Studies in Philology" 54 (1957): 516–36 (p. 525)

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Britannica 1911, 416.

- ↑ Britannica 1911, 417.

- ↑ Search results = au:Thomas Middleton, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Aug. 20, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- Selected Poetry of Thomas Middleton (c.1580-c.1627) ("To Teach my Base Thoughts Manners") at Representative Poetry Online

- Thomas Middleton 1580-1627 at the Poetry Foundation

- Thomas Middleton at PoemHunter ("How Near Am I to Happiness")

- Thomas Middleton at Poetry Nook (24 poems)

- Plays

- The Plays of Thomas Middleton

- Bilingual editions (English/French) of two Middleton plays by Antoine Ertlé:(A Game at Chess); (The Old Law)

- About

- Thomas Middleton in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Thomas Middleton at Biography.com

- Thomas Middleton at NNDB

- Middleton, Thomas (1570?-1627) in the Dictionary of National Biography

- Thomas Middleton (c.1580-1627) at Luminarium

- ThomasMiddleton.org - The Oxford Middleton Project

- Middleton and Rowley in the Cambridge History of English and American Literature

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.. Original article is at "Middleton, Thomas"

|