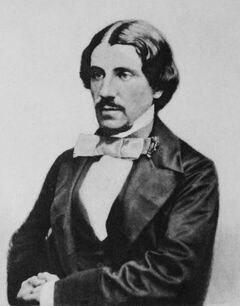

William Allingham (1824-1889) from Poems by William Allingham, 1912. Courtesy Internet Archive.

| William Allingham | |

|---|---|

| Born |

March 19 1824 Ballyshannon, co. Donegal, Ireland |

| Died |

November 18 1889 (aged 65) Hampstead, London |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | poet, scholar |

William Allingham (19 March 1824 - 18 November 1889) was an Irish poet and man of letters.

Life[]

Overview[]

Allingham, the son of a banker of English descent, was born at Ballyshannon, entered the customs service, and was ultimately settled in London, where he contributed to Leigh Hunt's Journal. Hunt introduced him to Carlyle and other men of letters, and in 1850 he publihed a book of poems, which was followed by Day and Night Songs (1854), Laurence Bloomfield in Ireland (1864) (his most ambitious, though not his most successful work), and Collected Poems in 6 volsume (1888-93). He also edited The Ballad Book for the Golden Treasury series in 1864. In 1870 he retired from the civil service and became sub-editor of Fraser's Magazine under Froude, whom he succeeded as editor (1874-1879). His verse is clear, fresh, and graceful. He married Helen Paterson, the water colorist, whose idylls have made the name of "Mrs. Allingham" famous also. He died in 1889. A selection from his diaries and autobiography was published in 1906.[1]

Youth and education[]

Allingham was born at Ballyshannon, co. Donegal, on 19 March 1824. William Allingham, his father, who had formerly been a merchant, was at the time of his birth manager of the local bank; his mother, Elizabeth Crawford, was also a native of Ballyshannon. The family, originally from Hampshire, had been settled in Ireland since the time of Elizabeth.[2]

Allingham entered the bank with which his father was connected at the age of 13, and strove to perfect the scanty education he had received at a boarding-school by a vigorous course of self-improvement.[2]

Career[]

William Allingham (1824-1889) from a 1908 engraving. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

At the age of 22 he received an appointment in the customs, successively exercised for several years at Donegal, Ballyshannon, and other towns in Ulster. He nevertheless paid almost annual visits to London, the first in 1843, about which time he contributed to Leigh Hunt's Journal, and in 1847 he made the personal acquaintance of Hunt, who treated him with great kindness, and introduced him to Carlyle and other men of letters. Through Coventry Patmore he became known to Tennyson, as well as to Rossetti and the pre-Raphaelite circle in general. The correspondence of Tennyson and Patmore attests the high opinion which both entertained of the poetical promise of the young Irishman.[2]

His debut volume, entitled simply Poems (London, 1850, 12mo), published in 1850,[2] with a dedication to Leigh Hunt, was nevertheless soon withdrawn, and his next venture, Day and Night Songs (1854, London, 8vo), though reproducing many of the early poems, was on a much more restricted scale. Its decided success justified the publication of a 2nd edition next year, with the addition of a new title-piece, "The Music Master," an idyllic poem which had appeared in the volume of 1850, but had undergone so much refashioning as to have become almost a new work. A 2nd series of 'Day and Night Songs' was also added. The volume was enriched by 7 very beautiful wood-cuts after designs by Arthur Hughes, as well 1 each by Millais and Rossetti, which rank among the finest examples of the work of these artists in book illustration.[3]

Allingham was at this time on very friendly terms with Rossetti, whose letters to him, the best that Rossetti ever wrote, were published by Dr. Birkbeck Hill in the Atlantic Monthly for 1896. Allingham afterwards dedicated a volume of his collected works to the memory of Rossetti, "whose friendship brightened many years of my life, and whom I never can forget." Many of the poems in this collection obtained a wide circulation through Irish hawkers as broadside halfpenny ballads.[3]

In 1863 Allingham was transferred from Ballyshannon, where he had again officiated since 1856, to the customs house at Lymington. In the preceding year he had edited Nightingale Valley (reissued in 1871 as Choice Lyrics and short Poems; or, Nightingale Valley), a choice selection of English lyrics; in 1864 he edited The Ballad Book for the 'Golden Treasury' series.[3]

Another reprint from Fraser was the Rambles of Patricius Walker, lively accounts of pedestrian tours, which appeared in book form in 1873. In 1865 he published Fifty Modern Poems, 6 of which had appeared in earlier collections. The most important of the remainder are pieces of local or national interest. Except for Songs, Ballads, and Stories (1877), chiefly reprints, and an occasional contribution to the Athenæum, he printed little more verse until the definitive collection of his poetical works in 6 volumes (1888–93); this edition included 'Thought and Word,' 'An Evil May-Day: a religious poem' which had previously appeared in a limited edition, and 'Ashley Manor' (an unacted play), besides an entire volume of short aphoristic poems entitled Blackberries, which had been previously published in 1884.[2]

In 1870 Allingham retired from the civil service, and removed to London as sub-editor (under James Anthony Froude) of Fraser's Magazine, to which he had long been a contributor. 4 years later he succeeded Froude as editor, and on 22 Aug. 1874 he married Miss Helen Paterson {born 1848), eldest child of Dr. Alexander Henry Paterson, known under her wedded name as a distinguished water-colour painter. He conducted the magazine with much ability until the commencement, in 1879, of a new and shortlived series under the editorship of Principal Tulloch. His editorship was made memorable by the publication in the magazine of Carlyle's "Early Kings of Norway," given to him as a mark of regard by Carlyle, whom he frequently visited, and of whose conversation he has preserved notes which it may be hoped will one day be published.[3]

After the termination of his connection with Fraser, lie took up his residence, in 1881, at Witley, in Surrey. In 1888 he moved to Hampstead with a view to the education of his children. His health was already much impaired by the effects of a fall from horseback, and he died about a year after his settlement at Lyndhurst Road, Hampstead, on 18 November 1889. His remains were cremated at Woking.[3]

Writing[]

Though not ranking among the foremost of his generation, Allingham, when at his best, is an excellent poet, simple, clear, and graceful, with a distinct though not obtrusive individuality. His best work is concentrated in his Day and Night Songs (1854),[3] which, whether pathetic or sportive, whether expressing feeling or depicting scenery, whether upborne by simple melody or embodying truth in symbol, always fulfil the intention of the author and achieve the character of works of art. The employment of colloquial Irish without conventional hibernicisms was at the time a noteworthy novelty.[4]

In 1864 appeared Laurence Bloomfield in Ireland, a poem of considerable length in the heroic couplet, evincing careful study of Goldsmith and Crabbe, and regarded by himself as his most important work. It certainly was the most ambitious, and its want of success with the public can only be ascribed to the inherent difficulty of the subject. The efforts of Laurence Bloomfield, a young Irish landlord returned to his patrimonial estate after an English education and a long minority to raise the society to which he comes to the level of the society he has left, form a curious counterpart to the author's own efforts to exalt a theme, socially of deep interest, to the region of poetry. Neither Laurence Bloomfield nor Allingham is quite successful, but neither is entirely unsuccessful, and the attempt was worth making in both instances. The poem remains the epic of Irish philanthropic landlordism, and its want of stirring interest is largely redeemed by its wealth of admirable description, both of man and nature. Turgeneff said, after reading it, "I never understood Ireland before."[3]

"The Music Master" (1865), though of no absorbing interest, is extremely pretty, and although "Laurence Bloomfield" will mainly survive as a social document, the reader for instruction's sake will often be delighted by the poet's graphic felicity.[4]

The rest of Allingham's poetical work is on a lower level; there is, nevertheless, much point in most of his aphorisms, though few may attain the absolute perfection which absolute isolation demands.[4]

Recognition[]

On 18 June 1864 Allingham obtained a pension of £60 on the civil list, and this was augmented to £100 on 21 January 1870.[3]

2 portraits, representing Allingham in middle and in later life, are reproduced in the collected edition of his poems.[4]

A collection of prose works entitled Varieties in Prose was posthumously published in 3 volumes in 1893.[4]

His poem "The Fairies" was included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[5]

Ulster poet John Hewitt felt Allingham's influence keenly, and his attempts to revive his reputation included editing and writing an introduction to The Poems of William Allingham (Oxford University Press/ Dolmen Press, 1967).

In popular culture[]

The opening lines from Allingham's poem "The Fairies" ("Up the airy mountain/Down the rushy glen/We daren't go a-hunting/For fear of little men...") were quoted near the beginning of the movie Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (by the character of "The Tinker), as well as in Mike Mignola's comic book short story Hellboy: The Corpse, plus the 1973 horror film Don't Look in the Basement. Several lines of the poem are quoted by Henry Flyte, a character in issue #65 of the Supergirl comic book, August 2011.

This same poem was quoted in Andre Norton's 1990 science fiction novel Dare To Go A-Hunting (ISBN 0-812-54712-87).

"Up the Airy Mountain" is the title of a short story by Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald.

The working title of Terry Pratchett's The Wee Free Men was "For Fear Of Little Men".

The Allingham Arms Hotel in Bundoran, county Donegal, is named after him.[6]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Poems. London: Chapman & Hall, 1850.

- Day and Night Songs. London: Routledge, 1854.

- Peace and War. London: Routledge 1854.

- The Music Master: A love story; and Two Series of Day and Night Songs. London: Routledge, 1855.

- also printed as Day and Night Songs, and The Music Master: A love poem. London: Bell & Daldy, 1860.[7]

- Poems. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1861;[7]

- reprinted, Boston: Fields, Osgood, 1870.

- Laurence Bloomfield in Ireland: A modern poem. London & Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1864; facsimile edition, New York: AMS Press, 1972.

- Laurence Bloomfield in Ireland, or The new landlord. London: Macmillan, 1869.[7]

- Laurence Bloomfield; or, Rich and poor in Ireland. London: Reeves & Turner, 1890.

- Fifty Modern Poems. London: Bell & Daldy, 1865.

- Songs, Ballads, and Stories. London: G. Bell, 1877.

- Evil May Day London: David Stott, 1883.

- Blackberries: Picked off many bushes, by D. Pollex and others; put in a Basket by W. Allingham. London: G. Philip & Son, 1884.

- Blackberries: Revised. London: Reeves & Turner, 1890.

- Irish Songs and Poems. London: Reeves & Turner, 1887.

- Flower Pieces, and other poems. London: Reeves & Turner, 1888.

- Life and Phantasy. London: Reeves & Turner, 1889.

- Thought and Word; and Ashby Manor: A play in two acts. London: Reeves & Turner, 1890.

- Sixteen Poems (selected by W.B. Yeats). Dundrum, Ireland: Dun Emer, 1905; Shannon, Ireland: Irish University Press, 1971.[7]

- Poems (selected and arranged by Helen Allingham). London: Macmillan (Golden Treasury Series), 1912.

- By the Way: Verses, fragments, and notes (arranged by Helen Paterson Allingham). New York: Longmans Green, 1912.

- Poems (edited by John Hewitt). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press / Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1967.

Plays[]

- Ashby Manor: A play in two acts. London: David Stott, 1883.

- The Fairies. London: De La Rue, 1883.

Non-fiction[]

- Rambles (as "Patricius Walker"). London: Longmans Green, 1873.[7]

- Varieties in Prose. London: Longmans, Green, 1893. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

Juvenile[]

- In Fairyland: A series of pictures by Richard Doyle with a poem by William Allingham. London: Longmans, Green 1870.

- Rhymes for the Young Folk. London: Cassell 1887.

Edited[]

- Nightingale Valley: A collection, including a great number of the choicest lyrics and short poems in the English language. London: Bell & Daldy, 1860.[7]

- The Ballad Book: A selection of the choicest British ballads. London: Macmillan, (Golden Treasure Series), 1864.

Journals[]

- William Allingham: A diary (edited by Helen Paterson Allingham and Dollie Radford). London: Macmillan, 1907.

- William Allingham's Diary (edited by Geoffrey Grigson). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967; Fontwell, UK: Centaur Press, 1967.[7]

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy University College, Cork.[8]

William Allingham - The Fairies - poem

See also[]

References[]

Garnett, Richard (1901). "Allingham, William". In Sidney Lee. Dictionary of National Biography, 1901 supplement. 1. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 38-40.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Allingham, William," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Garnett, 38.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Garnett, 39.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Garnett, 40.

- ↑ "The Fairies", Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 4, 2012.

- ↑ Allingham Arms Hotel. Web, June 8, 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Search results = au:William Allingham, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, June 8, 2013.

- ↑ Allingham's Works, Poems by William Allingham (compiled by Beatrix Farber), CELT (Corpus of Electronic Texts), 2008, University College Cork. Web, Dec. 7, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- "The Fairies"

- 4 poems by Allingham: "Late Autumn," "Autumnal Sonnet," "Bramble-Hill," "Let me Sing of What I Know"

- Allingham, William (1824-1889) (3 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- William Allingham (1824-1889) at Sonnet Central (8 sonnets)

- Allingham in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "The Fairies," "Lovely Mary Donnelly," "The Sailor," "A Dream," "Half Waking," "Day and Night Songs"

- William Allingham at PoemHunter (50 poems)

- Poems by William Allingham, CELT

- Books

- Sixteen Poems by William Allingham selected by W.B. Yeats

- Works by William Allingham at Project Gutenberg

- William Allingham at Amazon.com

- About

- Allingham, William in the Dictionary of Irish Biography

- William Allingham in the Concise Oxford Companion to Irish Literature

- William Allingham" Allingham in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- William Allingham at NNDB

- William Allingham in the Dictionary of Irish Biography

- William Allingham at Donegal on the Net

- William Allingham at Lymington.org

- Chronology of William Allingham at CELT (Corpus of Electronic Texts)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Dictionary of National Biography, 1901 supplement (edited by Sidney Lee). London: Smith, Elder, 1901. Original article is at: Allingham, William]

|