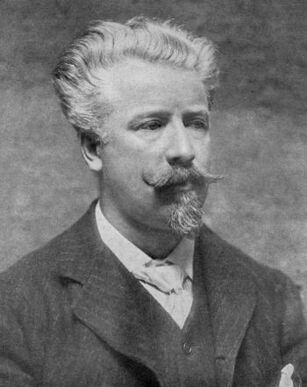

William Sharp (1855-1905) in Irish Plays and Playwrights (1913). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

William Sharp (12 September 1855 - 12 December 1905) was a Scottish poet and biographer, who from 1893 also wrote as Fiona MacLeod.

Life[]

Overview[]

Sharp wrote under the "Fiona McLeod" pseudonym a remarkable series of Celtic tales, novels, and poems. He was among the earliest and most gifted promoters of the Celtic Revival. In verse are From the Hills of Dream, Through the Ivory Gate, and The Immortal Hour (drama). Under his own name he wrote Earth's Voices, Sospiri di Roma, Sospiri d'Italia, poems, and books on Rossetti, Shelley, Browning, and Heine; also a few novels.[1] He edited the poetry of Ossian, Walter Scott, Matthew Arnold, Algernon Charles Swinburne and Eugene Lee-Hamilton.

Youth and education[]

Sharp was born at Paisley, the eldest son of David Galbraith Sharp, partner in a mercantile house, by his wife Katherine, eldest daughter of William Brooks, Swedish vice-consul at Glasgow. The Sharp family came originally from near Dunblane, his mother was partly of Celtic descent, but he owed his peculiar Celtic predilections either to the stories and songs of his Highland nurse or to visits 3 or 4 months each year to the shores of the western highlands.[2]

After receiving his early education at home he went to Blair Lodge school, from which with some companions he ran away 3 times, the last time in a vain attempt to get to sea as stowaways at Grangemouth. In his 12th year the family removed to Glasgow, and he went as day scholar to the Glasgow Academy.[2]

At Glasgow University, which he entered in 1871, he showed ability in the class of English literature; but it was mainly through access to the library that he found the university of advantage.

After spending a month or 2 with a band of gypsies, he was placed by his father, in 1874, in a lawyer's office in Glasgow, mainly with a view to discipline. While faithful to his office duties, he devoted himself to reading, the theatres, and similar diversions, allowing himself but 4 hours' sleep.[2]

After the death of his father in 1876 consumption threatened, and he went on a sailing voyage to Australia. Although he enjoyed a tour in the interior, the colonist's rough life was uncongenial, and he returned to Scotland resolved to "be a poet and write about Mother Nature and her inner mysteries."[2]

Early career[]

Without means or prospects, Sharp was about to join the Turkish army against Russia in 1878 when a friend found him a clerkship in London at the City of Melbourne Bank. Meanwhile he began to contribute verses to periodicals, and in 1881 he had the good fortune of obtaining from Sir Noel Paton an introduction to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who encouraged him with kindly criticism and advice. Through Rossetti he obtained access to many literary houses (see Life, p. 53).[2]

Failing to satisfy the requirements of the bank, he obtained a temporary post in the Fine Art Society's gallery in Bond Street;[2] but soon, depending wholly on his pen for a livelihood, he often ran risk of starvation.[3]

At the end of 1882 Sharp wrote a short life of Rossetti (who died that April). In 1882, too, appeared a volume of poems, The Human Inheritance, which obtained some recognition and led to an invitation from the editor of Harper's Magazine for other poems, which brought him £40. A cheque for £200 sent him by an unknown friend enabled him to study art in Italy for 5 months in 1883-1884. He contributed a series of articles on Etruscan cities to the Glasgow Herald, and was appointed art critic to the paper.[3]

Sharp was tall, handsome, fair-haired, and blue-eyed. On 31 October 1884 he married Elizabeth, daughter of his father's elder brother, Thomas Sharp, by Agnes, daughter of Robert Farquharson of Breda and Allargue; he had become secretly pledged to her in September 1875. There were no children.[4] The same year he published a 2nd volume of verse, Earth's Voices, vividly impressionist, but somewhat diffuse.[3]

Also in 1884 he became editor of the 'Canterbury Poets,' contributing himself editions of Shakespeare's Sonnets (1885), English Sonnets (1886), American Sonnets (1889), and Great Odes (1890). For a series of 'Biographies of Great Writers' he wrote on Shelley (1887), Heine (1888), and Browning (1890). He also published "The Sport of Chance" (1888), a sensational story, for the People's Friend; contributed boys' stories to Young Folks (which he edited in 1887); and published Romantic Ballads and Poems of Phantasy (1888; 2nd edit. 1889), fluently fanciful but lacking in finish, and The Children of To-morrow (1889), a romantic tale, in which he voiced his impatience of conventionality.[3]

Travels[]

A visit in the autumn of 1889 to the United States and Canada reawakened his desire to wander. After a stay of some months in the summer of 1890 in Scotland and a tour through Germany, he went in the late autumn to Rome, where he wrote a series of impressionist unrhymed poems in irregular metre, Sospiri di Roma, printed for private circulation in 1891. In the spring of that year he left Italy for Provence on the way to London, where he completed the Life and Letters of Joseph Severn (published in 1892). Subsequently at Stuttgart he collaborated with the American novelist, Blanche Willis Howard, in a novel, A Fellowe and his Wife (published in 1892).[3]

In the winter of 1891-1892 he was again in America, when through an introduction from his friend, the American poet, E.C. Stedman, he had an interview with Walt Whitman. He also arranged for the publication in America of his Romantic Ballads and Sospiri di Roma in one volume, under the title 'Flower o' the Vine' (New York, 1892).[3]

The spring of 1892 was spent in Paris and the summer in London; and in the autumn he rented Phenice Croft, a cottage in Sussex, where, probably under the impulse of the Whitman visit and in a fit of irresponsible high spirits, he projected the ’Pagan Review,' edited by himself as "W.H. Brooks" and wholly written by himself under various pseudonyms. Only one number appeared; and, owing to his wife's unsatisfactory health, he set himself to the completion of 2 stories for Young Folks, in order to obtain money to spend the winter in North Africa.[3]

Returning to England in the spring of 1893, he, while busy with articles and stories for the magazines, prepared a series of dramatic interludes, entitled Vistas — "vistas of the inner life of the human soul, psychic episodes" (published 1894).[3]

Fiona Macleod[]

137-The Mystery of Fiona Macleod

At Rome in 1890 he began a friendship with a lady who, "because of her beauty, her strong sense of fife and of the joy of life," stood as a "symbol of the heroic women of Greek and Celtic days, ... unlocked new doors" within him, and put him "in touch with ancestral memories" (Life, 223). Sharp thenceforth devoted himself to a new land of literary work, penning much mystical prose and verse under the pseudonym of "Fiona Macleod," whose identity he carefully concealed. Although in this phase of his literary production there was no collaboration with the lady of his idealism, he believed "that without her there would have been no Fiona Macleod."[3]

Much of the "Fiona" literature was written under the influence of a kind of mesmeric or spiritual trance, or was the record of such trances.[3]

The earliest of the books which Sharp wrote under the pseudonym of Fiona Macleod was begun at Phenice Croft in 1893. It appeared in 1894 as Pharais: A romance of the Isles, and Sharp declared it to have been written "with the pen dipped in the very ichor of my life."[3]

The Fiona series was continued in 1895 in The Mountain Lovers, "more elemental still" (1895), and The Sin Eater, consisting of Celtic tales and myths "recaptured in dreams" (1896). The latter volume was published by Patrick Geddes & Colleagues, a firm established in Edinburgh by Professor Geddes, with Sharp as literary adviser, for the publication of Celtic literature and works on science.[3]

There quickly followed The Washer of the Ford (1896), a collection of tales and legendary moralities; Green Fire, a Breton romance (1896), a portion of which, entitled "The Herdsman," was included in the Dominion of Dreams (1899; revised American edit. 1901; German trans, Leipzig, 1905); From the Hills of Dream, poems and "prose rhythms" (Edinbirgh 1896; new edition, London 1907);[3] The Laughter of Peterkin, a Christmas book of Celtic tales for children (1897); and The Divine Adventure: Iona, by sundown shores (1900), a series of essays.[4]

A Celtic play by Fiona, The House of Usna, was performed by the Stage Society at the Globe Theatre on 29 April 1900; and after its appearance in the National Review on 1 July was issued in book form in America in 1903. Another drama, The Immortal Hour, was printed in the Fortnightly Review (Nov. 1900; reissued posthumously in America in 1907 and in London in 1908).[4]

Fiona was also a contributor of articles to periodicals, many of which were collected, as The Winged Destiny (1904) and Where the Forest Murmurs (1906). Selections of Fiona tales appeared in the Tauchnitz series as Wind and Wave (Leipzig, 1902; German translation, Leipzig, 1905; Danish translation, Stockholm, 1910), and as The Sunset of Old Tales (1905). A uniform edition of Fiona's works was published in England in 1910.[4]

The secret of Sharp's responsibilities for the Fiona literature was well kept in his lifetime. He encouraged the popular assumption that Macleod was a young lady endowed with "the dreamy Celtic genius."[4] As late as 13 May 1899 Fiona Macleod wrote to the Athenaeum stating that she wrote only under that name and that it was her own.[5]

Sharp contributed to Who's Who a fictitious memoir of Macleod, describing her favourite recreations as "boating, hill-climbing, and listening," and he corresponded with her admiring readers through the hand of his sister.[4]

Educated Highland Celts detected in the books the imperfection of the supposed lady's Celtic equipment. While her work reflected the influence of old Celtic paganism, it was chiefly coloured by a rapturous worship of nature and mirrored the insistent vividness and weirdness of dreams.[4]

Other writings[]

Meanwhile Sharp, under his own name, found it needful, both for pecuniary reasons and for the preservation of the Fiona mystery, to be as productive as before. Fiction mainly occupied him. Of 2 volumes of short stories, The Gypsy Christ, published in America in 1895, was reissued in 1896 in England as Madge o' the Pool, and the other, Ecce Puella, appeared in London in 1896. Later works of fiction were Wives in Exile, a comedy in romance (Boston, Mass. 1896; London 1898) and Silence Farm, a tale of the Lowlands (1899).[4]

With Mrs. Sharp he edited in 1896 Lyra Celtica, an anthology of Celtic poetry, with introduction and notes; there followed The Progress of Art in the Century (1902; 2nd edition 1906) and Literary Geography (from the Pall Mall Magazine; 1904; 2nd edition 1907). In 1896-1897 he was also editor of a quarterly periodical, the Evergreen, issued by the Grades firm.[4]

2 volumes of papers, critical and reminiscent, containing some of the best work of William Sharp, are included in a reissue of some of his writings (1912).[4]

Death[]

The Fiona development, implying the 'continual play of the 2 forces in him, or of the 2 sides of his nature,' produced ’a tremendous strain on his physical and mental resources, and at one time, 1897–8, threatened him with a complete nervous collapse' (Life, p. 223). He found relief in travel and change of scene: the Highlands, America, Rome, Sicily, Greece, were all included in a constantly recurring itinerary. But his restless energy gradually undermined his constitution.[4]

After a cold caught during a drive in the Alcantara valley in Sicily he died at Castle Maniace, the home of his friend, the Duke of Brontë, to the west of Mount Etna, on 14 December 1905.[4]

He left a letter, to be communicated to his friends, explaining why he found it necessary not to disclose his identity with Fiona.[4]

Recognition[]

Barbara Bonney The complete "3 poems of Fiona Macleod" (Griffes)

Sharp was buried in a woodland cemetery on the hillside near Castle Maniace, where an Iona cross, carved in marble, has been erected.[4]

A painted portrait of him by Daniel Wehrschmidt and a pastel by Charles Ross were in the possession of his widow. There are also etchings by William Strang and Sir Charles Holroyd.[4]

In popular culture[]

Carson McCullers took the title of her 1940 novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, from a Fiona Macleod poem, "The Lonely Hunter," in Macleod's collection From the Hills of Dream.[6]

In Disney's 2017 movie production of Beauty and the Beast, the character of Belle (voiced by Emma Watson) recites to the Beast character several lines of Sharp's poem, A Crystal Forest, "Each branch, each twig, each blade of grass, / Seems clad miraculously with glass".[7]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Human Inheritance, The New Hope, Motherhood, and other poems. London: Elliot Stock, 1882.

- Euphrenia; or, The test of love: A poem. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1884.

- Earth's Voices:Transcripts from Nature, Sospitra, and other poems. London: Elliot Stock, 1884.

- Romantic Ballads and Poems of Phantasy. London: Walter Scott, 1888.

- Sospiri di Roma. Rome: privately printed, 1891.

- Flower o' the Vine: Romantic ballads and Sospiri di Roma.New York: C.L. Webster, 1892.

- The Distant Country, and other prose poems. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1907.

- Poems (selected and arranged by Mrs. William Sharp). London: Heinemann, 1912; New York: Duffield, 1912.

- as Fiona MacLeod

- From the Hills of Dream: Mountain songs and island runes. Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1896.

- From the Hills of Dream: Threnodies, songs, and other poems. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1901.

- The Silence of Amor: Prose rhythms. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1902.

- The Hour of Beauty: Songs and poems. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1907.

- Songs and Poems: Old and new. London: Elliot Stock,

- Runes of Woman: Poems. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1915.

Songs[]

- Three Poems by Fiona MacLeod: In musical settings. New York: G. Schirmer, 1918.

Plays[]

- Vistas. Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1894.

- as Fiona MacLeod

- The Black Madonna. London: W.H. Brooks, 1892.

- The House of Usna: A drama. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1903.

- The Immortal Hour: A drama in two acts. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1907; London: Heinemann, 1908.

Novels[]

- The Sport of Chance. (3 volumes), London: Hurst & Blackett, 1888. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- Children of To-morrow: A romance. London: Chatto & Windus, 1889; New York: F.F. Lovell, 1890.

- A Fellowe and His Wife (with Blanche Willis Howard). Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1892.

- Wives in Exile: A comedy in romance. London: Archibald Constable, 1896; Boston & New York: Lamsson, Wolfe, 1896.

- Silence Farm. London: Grant Richards, 1899.

- as Fiona MacLeod

- Pharais: A romance of the isles. Derby, UK: Harpur & Murray, 1894; Boston: Stone & Kimball, 1895.

- The Mountain Lovers. London: John Lane / Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1895.

- Green Fire: A romance. Westminster, UK: Archibald Constable, 1896; New York: Harper, 1896.

- The Divine Adventure. London: Chapman & Hall, 1900; Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1903.

- Deirdre and the Sons of Usna. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1903.

Short fiction[]

- The Gypsy Christ, and other tales. Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1895; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

- as Fiona MacLeod

- The Sin-Eater, and other tales. Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1895; Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1895

- also published as The Sin-Eater, and other tales and episodes. Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1895; New York: Duffield, 1907; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

- The Sin-Eater. London: Heinemann, 1912; West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press, 1985.

- The Washer of the Ford, and other legendary moralities. Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1896; Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1896.

- The Laughter of Peterkin: A retelling of old tales of the Celtic wonderworld (illustrated by Sunderland Rollinson). London: Archibald Constable, 1897.

- Spiritual Tales. Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1897.

- Tragic Romances. (3 volumes), Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1897; London: David Nutt, 1903. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- Songs and Tales of St. Columba and His Age, 13th centenary. Edinburgh: Patricke Getted, 1897.

- Re-Issue of the Shorter Stories of Fiona Macleod : rearranged with additional tales. (3 volumes), Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1897; London: David Nutt, 1903. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- The Dominion of Dreams. Westminster, UK: Archibald Constable, 1899.

- Ulad of the Dreams (novelette). Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1904.

- Three Legends of the Christ Child. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1908.

- The Hills of Ruel, and other stories. London: W. Heinemann, 1921; New York: Duffield, 1921.

Non-fiction[]

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti: A record and a study. London: Macmillan, 1882.

- Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley. London: Walter Scott, 1887.

- Life of Heinrich Heine. London: Walter Scott / New York: Thomas Whittaker / Toronto: W.J. Gage, 1888.

- Life of Robert Browning. London: Walter Scott, 1890.

- Life and Letters of Joseph Severn. London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1892; new York: Scribner, 1892.

- "Fair Women in Painting and Poetry", in The Portfolio (edited by P.G. Hamerton). London: Seeley; New York: Macmillan, 1894.

- Ecce Puella, and other prose imaginings. London: Elkin Mathews, 1896.

- Progress of Art in the Nineteenth century.London, Toronto, & Philadelphia: Linscott, 1902.

- revised and expanded as Progress of Art in the Century. Philadelphia & Toronto: Linscott; London & Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers, 1906.

- Literary Geography. London: Offices of the "Pall Mall Publications", 1904.

- revised and expanded as Literary Geography, and Travel sketches (selected & arranged by Mrs. William Sharp). London: W. Heinemann, 1912; New York: Duffield, 1912.

- Studies and Appreciations (edited by Mrs. William Sharp). London: William Heinemann, 1912; New York: Duffield, 1912; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1967.

- Papers, Critical and reminiscent (seleced & arranged by Mrs. William Sharp). London: W. Heinemann, 1912; New York: Duffield, 1912.

- as Fiona MacLeod

- By Sundown Shores: Studies in spiritual history. Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1902.

- The Winged Destiny: Studies in the spiritual history of the Gael. London: Chapman & Hall, 1904; London: Heinemann, 1910; New York: Duffield, 1910.

- The Isle of Dreams (from Iona). Portland, ME: Thomas B. Mosher, 1905; London: T.N. Foulis, 1913.

- Where the Forest Murmurs: Nature essays. London: C̀ountry Life / New York: Scribner's, 1906.

- A Little Book of Nature. London & Edinburgh: T.N. Foulis, 1909.

- At the Turn of the Year: Essays and nature thoughts. Edinburgh: T.N. Foulis, 1913.

Collected Editions[]

- Selected Writings (selected and arranged by Elizabeth A. Sharp [Mrs. William Sharp]). (2 volumes), London: Heinemann, 1912; New York: Duffield & Co., 1912.

- as Fiona MacLeod

- The Writings of "Fiona MacLeod". (selected and arranged by Elizabeth A. Sharp). London: William Heinemann, 1909-1910; New York: Duffield, 1909. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III, Volume IV, Volume V, Volume VI, Volume VII.

- Poems and Dramas (edited by Elizabeth A. Sharp). London: Heinemann, 1910.

Edited[]

- Sonnets of This Century (edited with introduction by Sharp). London: Walter Scott, 1886.

- Sea-Music: An Anthology of Poems (1887)

- American Sonnets. London: Walter Scott / New York & Toronto: W.J. Gage, 1889.

- Great Odes: English and American. London: Walter Scott, 1890.

- The Pagan Review 1. London: Rudwick, 1892.

- Lyra Celtica: An anthology of representative Celtic poetry (edited by Elizabeth A. Sharp & J. Matthay; introduction & notes by William Sharp). Edinburgh: Patrick Geddes, 1896; Edinburgh: John Grant, 1924.

William Sharp - A Crystal Forest ("The air is blue and keen and cold")

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[8][9]

See also[]

The Lonely Hunter by William Sharp

The Rose of the Night - Three Poems of Fiona MacLeod - Charles Griffes

References[]

Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1912). "Sharp, William". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement. 3. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 297-299.. Wikisource, Web, Mar. 2,2017.

- Elizabeth A. Sharp, William Sharp (Fiona Macleod): A memoir (1910, 1912)

- Flavia Alaya, William Sharp: "Fiona Macleod", 1855-1905 (1970)

- Terry L. Meyers, The Sexual Tensions of William Sharp: A study of the birth of Fiona Macleod, incorporating two lost works, "Ariadne in Naxos" and "Beatrice" (1996)

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Sharp, William," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 339-340. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 28, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Henderson, 297.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Henderson, 298.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Henderson, 299.

- ↑ Sharp, William (poet), Encyclopædia Britannica 1911 Volume 24. Wikisource, Web, Mar. 2, 2017.

- ↑ The secret behind the famous phrase “the heart is a lonely hunter”…, This Day in Quotes, June 6 2019. Web, Jun. 24, 2022.

- ↑ William Sharp (writer), Wikipedia, December 21, 2017. Web, Feb. 28, 2017.

- ↑ Search results = au:William Sharp 1855-1905, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Nov. 13, 2013.

- ↑ Search results = au:Fiona MacLeod, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Nov. 12, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- "The Lonely Hunter"

- Macleod in Modern British Poetry: "The Valley of Silence," "The Vision"

- Sharp in the Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse: "The Valley of Silence," "Desire," "The White Peace," "The Rose of Flame," "The Mystic's Prayer," "Triad"

- William Sharp at PoemHunter (3 poems)

- Sharp in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "The Last Aboriginal," "The Coves of Crail," "The Isle of Lost Dreams," "The Death-Child," Song ("Love in my heart")

- from Sospiri di Roma: I. "Susurro", II. "Red Poppies", III. "The White Peacock"

- Six Poems by Fiona MacLeod at the Lied, Art Song, and Choral Texts Archive

- Poems

- Books

- Works by William Sharp at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Fiona MacLeod at Project Gutenberg

- Collected Works of Fiona MacLeod, and Selected Writings of William Sharp at By Sundown Shores

- William Sharp at Amazon.com

- Fiona Macleod at Amazon.com

- About

- Sharp, William (poet) in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- William Sharp at Electric Scotland

- "The Little Book of the Great Enchantment" Biography of William Sharp by Steve Blamires (RJ Stewart Publications 2008)]

- William Sharp: The personality behind Fiona Macleod at Scotland.com

- By Sundown Shores: Fiona MacLeod & William Sharp website

- William Sharp (Fiona Macleod): A memoir by Elixabeth Sharp

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Dictionary of National Biography, 2nd supplement (edited by Sidney Lee). London: Smith, Elder, 1912. Original article is at: Sharp, William

|